Vemicious Knids: Mark Rosenblatt's Giant

On a play about Roald Dahl's antisemitism and the relationship between an artist's words and their work.

This week I’m still in Belgrade where the government’s current response to the ongoing protests is to penalise cultural organisations which have demonstrated support for the students. The Sterjjino Pozorje festival, the most prominent national theatre festival in Serbia, is one of many institutions to find its funding allocation reduced to zero, putting its future in jeopardy. I wrote a little bit about this act of cultural vandalism in this month’s column for The Stage.

This week’s newsletter, however, is about a show I saw a while back in London but which really left an impression on me.

If you want to support my writing and gain access to occasional paid subscriber bonus posts, you can do so for just £5 a month or £50 a year. Or, if that’s not doable - you work in theatre, I get it - just share this newsletter with someone you think might find it interesting. That helps too.

The title of Mark Rosenblatt’s play, Giant, is apt in more ways than one. Yes, it’s nod to the fact that the author Roald Dahl, the creator of the BFG, was himself both physically imposing and something of an outsize character, but also to the fact he was an enormous figure in the childhoods of many. He was huge. His writing permeated my school days. Like a lot of bookish girls, I loved Matilda and gobbled up everything else he wrote – I had a real soft spot for The Magic Finger. So much of his writing demonstrated a deep understanding of children’s innate sense of injustice, not to mention their love of all things icky.

With Dahl, more than any other author, I also remember being aware of the person behind the words on the page from a young age. This was largely down to his two volumes of memoirs, particularly Boy, his account of his time at Repton in the 1930s which is stuffed with descriptions of the brutality of the English public school system, to ‘fagging’, small boys being used as toilet-seat warmer, and children being caned until they bled (by a future Archbishop of Canterbury no less), as well as an almost gleeful account of the time he nearly got his nose sliced off in a car accident when he was nine. In the follow-up Going Solo, about his time working for Shell and in the RAF, he vividly describes his plane being shot down in the Middle East leaving him seriously injured (something which he also wrote about here).

There was also a TV movie, The Patricia Neal Story, which was on the box a lot in the 80s and starred Dirk Bogarde as Dahl and Glenda Jackson as his wife, the actor Patricia Neal, who suffered a debilitating stroke while pregnant. Dahl refused to accept that she would not recover and helped establish an intensive rehabilitation programme for her. (In this fascinating article by Tom Solomon, he explores the idea that Neal’s aphasic neologisms may have had some influence on the distinctive speech of the BFG).

So I had a clearer picture in my head of Dahl than of most authors at the time, a vivid image of this prickly, dyspeptic product of the English public school system who at the same time was capable of writing works that delighted and transported me as a young reader. It was only as an adult, however, that I became aware of some of his views and pronouncements and felt that all-too-familiar souring when you discover someone whose work you love has said or done something beyond the pale.

Dahl’s antisemitism fuels Rosenblatt’s play, which debuted at the Royal Court Theatre last year before transferring to the Harold Pinter Theatre in the West End. It is a solidly old-fashioned piece in many ways, a play in which people trade polished barbs over salad niçoise, but also a play that, despite being written before the horror of October 7 and all the horror that has followed – Rosenblatt started writing it in 2018 - manages to speak eloquently to the current moment, while also posing questions about the relationship between an artist’s words and their work, and whether or not it’s possible to separate them.

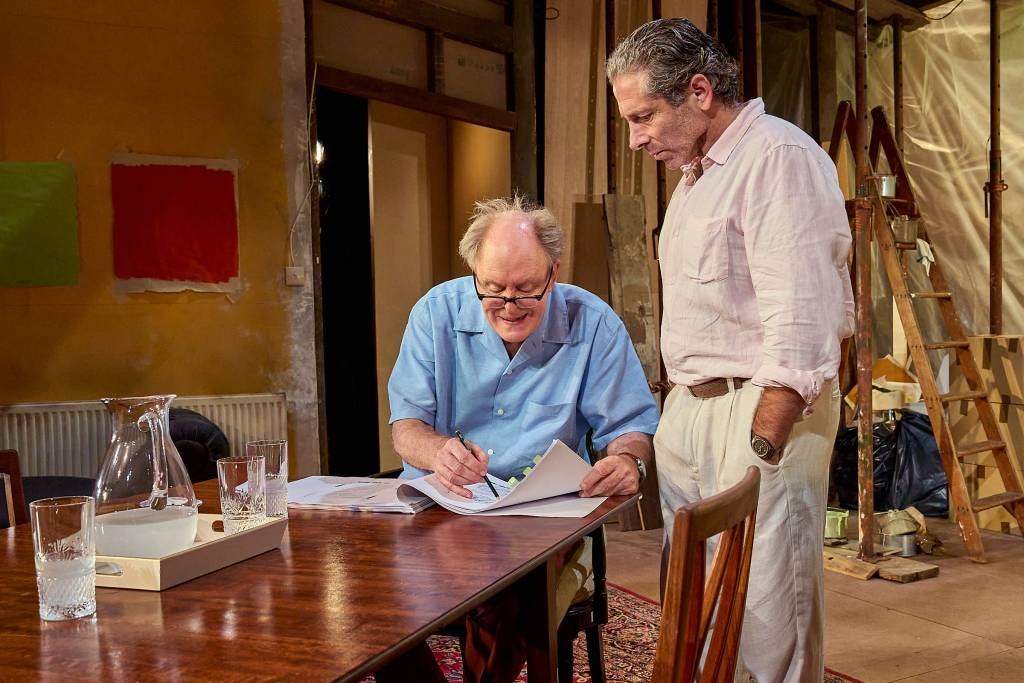

Giant is set on summer’s day in 1983, with the publication of The Witches imminent. Dahl and his soon-to-be-wife Felicity Crosland (Rachael Stirling) are about to have lunch with his British publisher Tom Maschler (Elliott Levey), the real-life head of Jonathan Cape. They’re in the process of going over the proofs of Dahl’s new book, but Maschler is really there to get Dahl to address the matter of a recent review he’s written for the Literary Review of a book about the Israeli war in Lebanon, which was brazenly antisemitic in its argument. Maschler feels it would be beneficial to everyone if Dahl would issue an apology but that this would involve him conceding he’d done something to apologise for.

His American publishers have dispatched an emissary, Jessie Stone (Romola Garai at the Royal Court, Aya Cash when I saw it in the West End) to help persuade him. Unlike Maschler, she’s a fictional character; both, however, are Jewish as Dahl wastes absolutely no time in ascertaining.

Rosenblatt presents Dahl as a man of passion, doggedness and impish wit who is still carrying around the emotional wound left by the death of his daughter and is also in considerable physical pain from a chronic bad back. He is a browbeater par excellence. He can be spectacularly cruel and brutally erudite but is also capable of tenderness and compassion. He affably delivers little digs designed to get under his guests’ skin; he is convivial in his bigotry, and yet he clearly does care deeply about the children being killed in Lebanon. When he deduces that Jessie Stone has a son with learning disabilities, he is gentle and sympathetic. Lithgow, who won an Olivier for his performance, captures all of this, the author’s grouchy charm, the way he teeters between irritation and near-glee while toying with his guests, the way he uses questions as weapons.

The other characters are similarly well-crafted. Levey, as Maschler, is the epitome of pragmatic professionalism. He’s a man who knows how to inhabit certain worlds and interact with certain people – he is in his element when talking about playing tennis with Ian McEwan - but it’s telling that he declines to eat with Dahl, preferring to pace the room. It’s such a good detail, his near-inability to sit. Maschler remains diplomatic, even as Dahl puts him on the spot. If Maschler, Dahl asks, believes him to be a raging antisemite and is still happy to tolerate him for the sake of sales, what does this say about him?

Though a fictional creation, Stone is not merely a catalyst. Though she clearly finds Dahl intimidating, she is capable of standing up to him and speaking her mind. After being repeatedly undercut and badgered by Dahl you can see her reach her tipping point, a place where she can no longer contain her anger. Cash makes us understand the courage that takes, the steel that requires.

As explored in this excellent Exeunt review, in which critic Alexander Cohen watched the play with his Jewish grandmother, both characters allow Rosenblatt to explore different facets of British and American Jewish identity. Maschler, whose family fled to the UK from Austria in the 1930s and who lost relatives in the Holocaust, reluctantly expresses frustration about being subject to a particularly pernicious type of moral scrutiny, forever being asked about Israel’s actions “as if I’m the fucking ambassador,” but only does so when pressed by Dahl. Stone is more comfortable calling out Dahl’s antisemitism for what it is, while also opening further cans of worms by suggesting that it is not wholly implausible that people might find The Witches – a book about a secret society of wig-wearing child-killers hiding in plain sight – antisemitic as well.

Rosenblatt only slowly reveals the full extent of Dahl’s hatred of Jews, how is antipathy towards Israel has tipped into full-blown antisemitism as he all but concedes. Though this feels organic, part of the dramatic texture of the play, it still elicits gasps from the audience. Rosenblatt waits until the very end of the play, however, before letting us hear, in full, the interview Dahl gave to journalist Michael Coren in the New Statesman in which he basically said maybe Hitler had a point for targeting Jews. “He didn’t pick on them for no reason.” (In this recent-ish piece Coren discusses that interview with Dahl and how it felt to be on the other end of this conversation.) Even having read these comments before, hearing Lithgow deliver them is something else entirely. That his phrasing, describing Hitler as “a stinker”, is so unmistakably Dahl-ian, somehow compounds things, not that what he said isn’t awful enough. A queasy silence hung over the audience as he spoke. It’s made clear that he knows exactly what he’s saying, and while his remarks are partly fuelled by a mile-wide contrarian streak, and his innate resistance towards everyone who’s been telling him to play nice over the last couple of hours, that he very much means it.

That this is Rosenblatt’s debut play makes it even more impressive. Elegantly and understatedly directed by Nicholas Hytner, its traditional form acting as a kind of cloaking device. It allows Rosenblatt to touch on topics that people either tiptoe around or feel so passionate about they struggle to speak about without things getting heated. While it presents us with Dahl’s undiluted views, it’s also a complex and arguably generous portrait of the writer. Rosenblatt crams in a lot of biographical information - there are references to his relationship with Neal, to his young son Theo, who received a brain injury when he was an infant and for whom Dahl, ever the innovator, helped develop a new kind of cerebral shunt to help manage his condition, and to devastating loss of his daughter Olivia from measles – yet it never feels effortful or overdone. Instead it helps us understand the man and what shaped him.

Despite everything Stone admits she still loves Dahl’s work, an impulse with which both she and the play wrestle. While it would be wrong to draw a direct comparison, the play inevitably makes you think about JK Rowling, her anti-trans stance and the impact it has had on her readers’ relationship with her work. (Waters which Lithgow himself waded into earlier this year having been cast as Dumbledore in the forthcoming Harry Potter television series).

Like Rowling, Dahl is also an industry, his work regularly adapted for stage and screen. The meeting at the heart of Rosenblatt’s play is essentially an exercise in reputational damage control, engineered primarily to avoid harming sales of The Witches - a book which incidentally has been adapted not once but twice for screen and was recently the basis of a musical at the National Theatre with a book by Lucy Kirkwood. In 2021, Netflix acquired the Roald Dahl Story Company, which licenses Dahl’s work to organisations wishing to adapt his stories, or as they put it, “protect and grow the cultural value of Roald Dahl’s work.” In 2020, presumably just as this deal was in the process of going through, Dahl’s family released an apology for his antisemitism. It’s on their website, though it has since been updated. Dahl’s posthumous role as an IP engine is the one area into which the play doesn’t really delve, though it’s clear that, now as then, it’s in the interests of an awful lot of people for Dahl’s work to remain palatable.

This makes the play, and its approach, feel even bolder. It’s neither an attack on Dahl, nor is it a ‘debate’ play, it’s something richer, a piece of complexity, contradiction, and arguable compassion that never once underestimates the power of language, the damage words can do and the way that hate is spread.

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days.

Ugly Sisters – Emerging theatre company piss / CARNATION’s fringe hit takes its inspiration from Australian feminist Germaine Greer and her response to the trans woman who thanked her following the publication of The Female Eunuch. It’s a bold and exposing, tender and adventurous piece which takes a nuanced look at feminist history and trans identity and it’s on at Soho Theatre in London from 25 June-12 July.

ECHO - There’s another chance to see Nassim Soleimanpour’s play about the temporal nature of exile, performed by a different performer every night. Actors confirmed for the return run include Juliet Stevenson, Dominic West and Reece Shearsmith. Directed by Omar Elerian, it’s at the Royal Court in London from 27 June - 5 July.

FITS - One of the biggest theatre and performing arts festivals in Europe, FITS takes place for 10 days in June in the city of Sibiu in Romania. The programme typically mixes work by renowned international theatre companies, local artists and student companies. Highlights this year include No Yoghurt for the Dead, the new show by Tiago Rodrigues, and a Romanian production of Uncle Vanya directed by Neil LaBute for “Radu Stanca” National Theater Sibiu. The festival opened on 20 June and runs until 29 June.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com