Word/play: Omar Elerian on directing Ionesco's Rhinoceros

On a new production of an absurdist classic at London's Almeida Theatre and why Ionesco's work still resonates.

Hello! This week I’m back in London - after a brief pitstop in Norway - and already my diary is filling up with shows.

Thanks to those who shared my last piece on the evolving situation in Serbia. It remains relatively under-reported given the scale of what’s going so I appreciate that. Here’s the newsletter, if you missed it.

If you want to support my writing while helping keep this Substack largely paywall-free (though there will be occasional paid subscriber bonus posts, like this one on Robert Lepage’s Faith, Money, War and Love), for this week you can still do so for just £4 a month or £40 a year. Or just share this newsletter with someone you think might find it interesting. That helps too.

The plays of Eugène Ionesco feature regularly in the repertoire of European theatres, but this is less true in the UK. A fringe production here or there maybe, but far less frequently on main stages. In 2022, Omar Elerian directed Ionesco’s The Chairs at London’s Almeida Theatre, a production notable for starring Kathryn Hunter and her late husband Marcello Magni. It was a production of vaudevillian melancholy and meta-theatre, performed with a mix of playfulness and precision by Hunter and Magni. (The Guardian called it a “hugely exciting revival”).

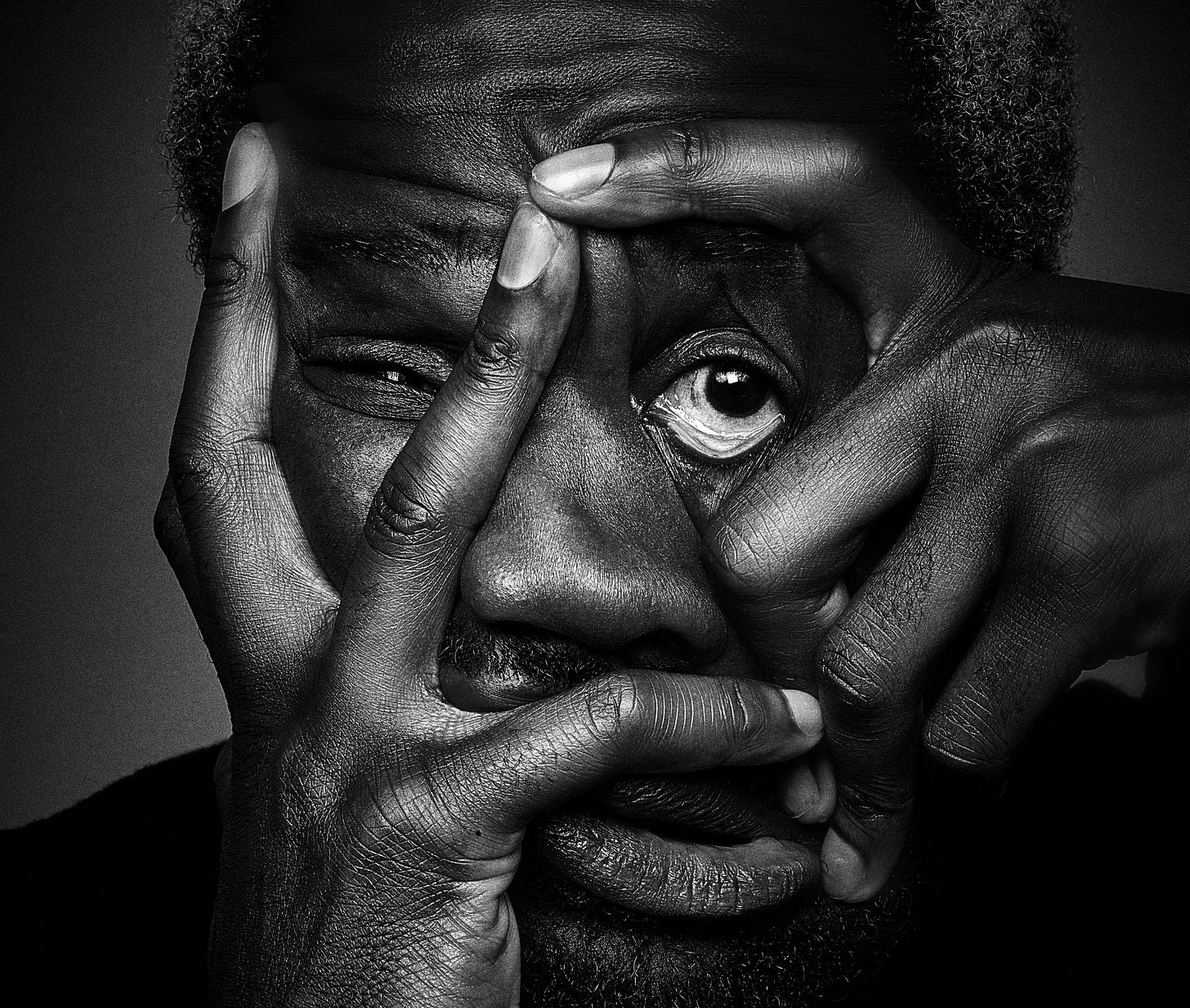

Now Elerian is back at the Almeida directing Ionesco’s 1959 play Rhinoceros with a cast including Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù, star of Slow Horses and UK horror His House (an underappreciated gem) and Sophie Steer (who has cropped up in this newsletter on more than one occasion).

What is it about Ionesco’s work, and specifically Rhinoceros – a play in which, one by one, the inhabitants of a small French town turn into rhinos – that appeals to Elerian? “Ionesco's interested in two things that interest me a lot, which are language and the conventions of theatre,” he says. People think of Rhinoceros as being a parable about the rise of Nazi fascism in Europe in between the two World Wars, he explains, “but rereading the play, and rereading a lot of Ionesco's writing, I was actually more intrigued by the fact that it's a play about conformism.”

“We live in a time where there is a huge polarization of thought,” he says. There’s little room for nuance when it comes to values. “If you accept one clause of values, then you automatically need to accept all the clauses on that side, and therefore you are against the other side.” This makes the play feel particularly timely and relevant to our current cultural moment.

Often, he says, “there is no time to develop an original or individual point of view, instead you are put into different categories, and then you start regurgitating ideas and prescriptions that belong to one side or the other.” Ionesco, he says, “nails the fact that this level of conformity exists across the political spectrum. It is not just the prerogative of the extreme right. Any idea or thought that becomes absolutist can draw people together, but at the same time, take away their capacity for reflection.”

Elerian is, to my mind, one of the most consistently interesting directors working in the UK. Born in Italy to an Egyptian-born Palestinian father and an Italian mother, he trained in Italy and studied at the renowned Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris, graduating in 2005. (“It’s not a theatre school as much as a school for life. It allows you to open up your perspective on the world,” he said in an earlier interview I did with him in The Stage). While resident Associate Director at the Bush Theatre, a role he held from 2012-19, he helmed Arinze Kene’s Misty, a genre-defying solo show exploring Blackness, storytelling and much else besides in which Kene was briefly encased in a huge orange latex balloon. It became a runaway hit, transferring to the West End and eventually having a run at The Shed in New York. While he was at the Bush, he also made Islands, a grotesque and excessive bouffon clown show about the UK’s status as a tax haven, which did decidedly less well (Time Out liked it, many others didn’t), but I think says a lot about his willingness to explore forms less familiar to UK audiences. I think the first time I encountered his work, however, was with the immensely charming solo show You’re Not Like The Other Girls Chrissy by Caroline Horton, with whom he went on to work on Islands.

He also has an ongoing collaborative relationship with Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour, the creator of White Rabbit, Red Rabbit, a play written to be performed unrehearsed by a different performer every night which has become something of a global phenomenon. They’ve since made two shows together - NASSIM and last year’s ECHO (Every Cold-Hearted Oxygen) at the Royal Court - and plan to do more. Together they have evolved Soleimanpour’s ‘cold read’ method of theatre-making. ECHO, which was also performed by a different actor at every performance, “is excellent on the nature of what it is to have a divided self as a result of emigration,” wrote Andrzej Lukowski in Time Out. (Here’s a great interview by Tom Wicker in The Stage on the making of that show).

“We're both artists who work in another culture and in another language,” says Elerian of his creative relationship with Soleimanpour. While the word ‘migrant’ has become “very loaded at the moment,” he says, their work is about what it is to lead a life away from where you are from. There’s a temporal element to living such a life which they are both interested in exploring. “There is a whole other timeline that develops.” The idea that migrants can simply ‘go back’ or ‘go home’ is, among other things, a gross simplification of what it’s actually like when you, by choice or as a result of external factors, find yourself living far from the place you come from. There is a process of divergence, a near permanent internal tug-of-war. “As a migrant, you're somebody who is always negotiating their space or their place into the world,” he says.

These ideas also percolate through Elerian’s international work. His 2021 production of Syrian playwright Mudar Alhaggi’s Return of Danton, a co production between Collective Ma'louba and Theater an der Ruhr, was “a Rubik’s cube of a play” about a group of Syrian artists trying to make theatre in Germany. The Stage called it “a nuanced piece of metatheatre.” More recently his 2023 production of As You Like It (another play of migration and shifting identity) for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon cast older British stage stalwarts Geraldine James and Malcolm Sinclair as Rosalind and Orlando.

With both Rhinoceros and The Chairs, Elerian has also translated the text. Language is clearly something he takes a great interest in. “It was a great opportunity and privilege to be able to go back to the original and try to mine from it something that can then serve the vision of the production.” With both plays “I tend to be quite faithful to the letter of the text,” he says. “In both endeavours my approach was always to go back to the original and try to capture what Ionesco was trying to do with the French language and try to translate that effort into English.”

Rhino-sightings on UK stages have been few and far between. There was a cut-down version by Patrick J O’Reilly at the Belfast International Festival in 2023 and Turkish director Murat Daltaban’s production at the Edinburgh International Festival in 2017, but the last major London production of the play was by Dominic Cooke for the Royal Court back in 2007, starring a cusp-of-fame Benedict Cumberbatch. (Here’s an interesting review of that production).

Why are we a bit wary of Ionesco in the UK in comparison to mainland Europe? “I haven't developed a fully coherent theory yet,” says Elerian, “Bur he refuted psychological realism. And I think the British tradition of playwriting is much more steeped in social realism and the idea of theatre being the mirror of the world.” With Ionesco, he says, “the moment in which you start psychologizing these characters, you inevitably find yourself in a complete chaos of contradictions, because they are not thinking in a linear, consequential way.” A lot of Ionesco's plays based themselves on the structure of a farce, he says, and the tradition of farce and satire in countries like France and Italy and other Catholic countries goes back to the tradition of Carnival, he explains, “which is a specific Catholic tradition, which was all about the reversal of authority and turning the world upside down.”

With The Chairs he had the opportunity to explore this with Hunter and Magni as well as Toby Sedgwick. He is clearly delighted at having had the opportunity to work with them. “They are so good at their craft, he says. “Often, as a director, you set up a scene in the way you want, and then you leave space for the actors to make offers. And with Kathryn and Marcello, they could do every scene in 12 different ways - and they were all brilliant.”

Now he’s back in the rehearsal room, clearly relishing working on another Ionesco text, preparing to put a play about the mechanisms of conformity in front of an audience. “This show is an experiment on multiple levels,” he says. “The protagonist Berenger becomes a surrogate of the audience. He is thrown into a weird petri dish where all sorts of things are happening around him and to him. Everyone’s going mad and he’s the last man standing,” he says.

These ideas will be extended to the theatre itself. “A theatre is a place of norms,” he says. “It is a place of internalized rules. From the moment in which we accept the transaction of buying a ticket and going to a numbered seat, we know the rules of theatre. We know when to shut up and switch off our phones and when to applaud and when to laugh.” Part of the evening, he says, will involve making the audience aware of those conventions and making them aware that they are part of the crowd, that although they are individuals, and have individual agency, at the same time, will they behave in the way they individually want, or will they conform to the prescription of the crowd?”

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days.

Absalom, Absalom! - Séverine Chavrier, director of the Comédie de Genève, tackles William Faulkner’s Southern Gothic epic in a five-hour fusion of performance and music which premieres at the Odéon-Théâtre in Paris on 26th March.

Hospital of Ghosts - Lars von Trier’s cult 1990s haunted hospital miniseries, known in English as The Kingdom and arguably one of the inspirations for Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, is the basis for a massive five-hour stage adaptation by Jan-Christoph Gockel and and Karla Mäder. It has its premiere at Berlin’s Deutches Theater on 29th March

Rhinoceros – As discussed above, Omar Elerian follows up his production of The Chairs starring Kathryn Hunter and her late husband Marcello Magni a couple of years back, with another Ionesco absurdist classic. It premieres at London’s Almeida Theatre on 1st April.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, thoughts or other comments you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

What an incredible photograph! Great work Natasha, it's a terrific and inspiring article.