Edinburgh Fringe round-up: Ugly Sisters, Instructions, The Happiness Index and Lessons on Revolution

On a group of shows doing interesting things with form.

I’m still at Edinburgh Fringe where I’ve notched up around 40 shows (which is such a weird way to consume art, but here we are), eaten a less than optimal amount of vegetables and discovered that if you really have to you can make it from Summerhall to the Pleasance Dome in eight minutes though you will be quite sweaty when you get there.

Keep an eye on The Stage for the latest reviews from me and the rest of the review team. In the meantime, I’ll be using this space to explore some of the other work I’m seeing.

Last week I looked at some of the (many) shows exploring grief, below are some of the shows I’ve found most formally exciting this year.

Here comes the slightly awkward part where I mention money. Café Europa is free and I’m really keen to keep it that way, but if you’d like to help sustain it, support my writing (and receive the occasional bonus edition - like this one about up-and-coming Greek director Mario Banushi - please consider becoming a paid supporter. You can do so for £5 or £50 a year. Or just share it with anyone you think will like it. That helps too.

Ugly Sisters, Underbelly

In 1970, Germaine Greer published The Female Eunuch, one of the seminal texts of second wave feminism. It had a profound impact at the time and remained essential reading when I was at university. In 1989, Greer published the essay On Why Sex Change is a Lie. In it she described an encounter with a trans woman, “a person in flapping draperies,” who thanked her for publishing the book. “Thank you so much for all you’ done for us girls!”

Greer recounts this exchange by sneeringly referring to her as ‘it’ and describing her hand as an “enormous, knuckly, hairy, be-ringed paw.” It’s a really mean-spirited bit of writing and it’s also the basis for this new show by young company piss/Carnation (great name), one of three recipients of the Untapped award, a scheme to support emerging makes.

This encounter between Greer and the trans woman sets of a spiralling exploration of womanhood and self-acceptance. The performers - Laurie Ward and Charli Cowgill - think themselves in the mind of the woman who had gone not just to meet Greer, but to thank her and what such a rejection must have felt like. They return to this moment again and again. In some versions of the retelling Greer, played by Cowgill in a sensible wig and (very unsensible) teetering Perspex heels, wearing a T-shirt that reads ‘adult human female’, ends up dead, deposited in the earth by people plucked by from the audience. She bounces back though, strutting and snapping across the stage. To be clear, this is not a piece that is any way advocating violence. Rather this is one of many symbolic gestures in a piece that is, crucially, not driven by anger, but more by sadness and disappointment that Greer’s feminism is not elastic enough to encompass their experiences.

The piece morphs and shifts, in one moment presenting us with a sexual experience between two trans women, the moment of passion undercut by the lingering, stinging rebuke: 'you'll never be a real girl'. There’s a real sense of risk and exposure here. When there are shows in town patting themselves on the back for saying the unsayable (while playing in a major venue and plenty of national press coverage), here’s a piece that finds a form to meld compassion with provocation. While it’s true that at the start, as Ward was racing around the stage in a knitted mask and ballgown while wielding a leaf-blower, I did a mental air-punch – this is exactly the kind of shit I want from the fringe - I was also struck by its generosity. This piece is not exclusionary, to Greer or anyone. The performers strip away the external trappings of gender and stand before us. It’s a show studded with gestures of tenderness - Cowgill invites someone from the audience to help braid her hair - and the ending is a delicate, perfectly judged gesture of solidarity

Instructions, Summerhall

Nathan Ellis’ work.txt was a play that was designed to be performed by its audience, it was a play about work that made its audience do the work, following a series of instructions and breaking the audience into segments, assigning them different tasks. According to Alice Saville’s review for Exeunt, “it felt like a church service, the mixture of stumbling reading aloud and earnestness, overlaid with something haunting and magical.”

Here Ellis builds on that idea, with a play that – as its name suggests – consists of a series of instructions, which a different actor is asked to follow each day. The actor has not rehearsed or seen the material beforehand, they are coming to the work as fresh as the audience. This is not an uncommon device– Nassim Soleimanpour does this in much of his work, but whereas in his work, it is often a way of reflecting on his absence in the room or in the country, as an artist in exile, Ellis has different aims.

The performer – Temi Wilkey on the day I see it (in Edinburgh with her own show, Main Character Energy) is fed orders through headphones and via a monitor in front of her, which she then follows. They tell her when to smile and what to say. They even instruct her to seek reassurance: “Am I doing OK?” she asks (reading from the screen).

A plot emerges. The actor is asked to play an actor auditioning for a film called Love in Paris, a generic romcom. She is asked to play a short scene and display a series of emotions, her face projected on the screen behind her. The actor is delighted to get the part, but then hears nothing more about the filming. Then the film is released and she discovers she is in it, without ever filming a scene.

The show is on one level about AI and the ways in which it might impact on the creative industry. But it’s also about the act of acting, and how it is a form of programming. We watch the actor make faces on command and stick out their tongue on cue. (The video of Temi is sometimes subject to a slight delay, adding an uncanny sheen to proceedings). And beyond that it’s maybe also a reflection on how so many of our interactions are about following instructions, about reacting to cues, making the right face at the right time. Writing about theatre I have deployed the trite phrase ‘It’s about what it is to be human’ on far too many occasions, but here it really applies.

I interviewed Ellis back in 2022, about his (more conventionally narrative-driven) play Super High Resolution and he’s someone who thinks really interestingly about form, something evident in work.txt which has toured internationally, and here too.

Jonny and the Baptists: The Happiness Index, Assembly George Square

Jonny and the Baptists are a musical comedy duo. They consist of Jonny Donahoe, the star and co-creator of Duncan Macmillan’s Every Brilliant Thing, back at the fringe this year for 10th anniversary victory lap, and his co-writer and musician Paddy Gervers. They write silly songs about bonking in libraries and absurdist ditties about Quentin Blake. They’re also one of the most explicitly political comedy acts about, who once concluded a show with a call to abolish inherited wealth; in 2014, two years before Brexit they also made a show called Stop UKIP, which proved depressingly prescient in which they warned against treating Nigel Farage as a benign comedy character who likes a pint, instead of a credible threat to the political stability of the UK (see how well that went).

In 2021, I interviewed them along with Sh!t Theatre’s Rebecca Biscuit and Louise Mothersole as part of a piece about how double-acts, people accustomed to creating together, were fairing during the pandemic (in their case the short answer was: not well). This show is kind of about that. It’s about mental health, and the difficulty of accessing treatment in an NHS that has been gutted by 14 years of Tory austerity. It’s about their own struggles with depressions. It's also a show about love and how a creative partnership can blossom into an emotionally supportive relationship. This manifests in multiple ways. An injury means Gervers is less mobile than usual, so Donahoe has to race around the stage and do all the physical stuff.

Wearing colourful onesies and performing in front of a beach backdrop, with the word ‘help’ written in pebbles on the floor, they joke that they only got funding because they told the Arts Council they were doing The Tempest, which prompts a potted history of arts funding in the UK. The show takes its title from a survey commissioned when David Cameron was in power to assess and quantify the contentedness of the nation.

Their shows have always had a degree of narrative cohesion – yes, there are silly songs, but there is always an overarching theme. This is true here, with the show executing an emotional pivot in its last 10 minutes that genuinely upended me. Gervers lost his mother at a young age, something they have discussed in their work and in the play’s climactic moments the tone suddenly shifts from general sweaty tomfoolery to something more emotionally naked. Directed by James Rowland, a man with a strong track record at making audiences sob in his own storytelling work, this is a hard show to put in a box, but I have seen so many shows that signal what they’re doing and how they’re doing it in the first 10 minutes, so this was refreshing and it felt more dramaturgically rigorous than a lot of the more conventional theatre I’ve seen.

Lessons on Revolution, Summerhall

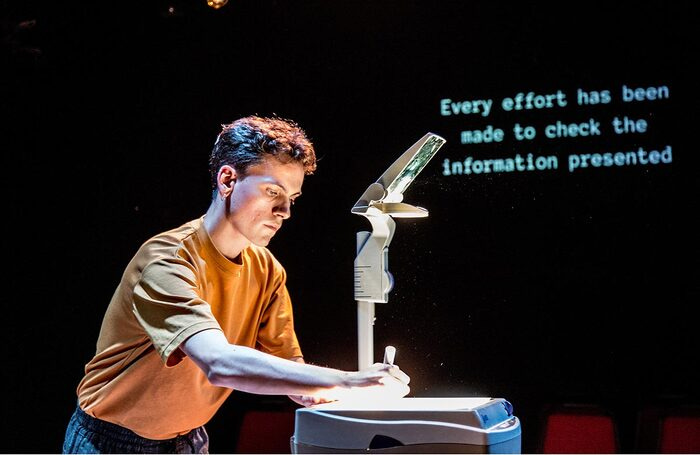

This piece of documentary theatre by Sam Rees and Gabriele Uboldi is shaping up to be one of my favourites of this year’s fringe. Here’s my review in The Stage. It’s a show about the student protests that took place at LSE in the 1960s, which led to more than 3,000 students occupying the school. It explains why they were protesting – concerns over connections between the institution and what was then Rhodesia - and who led the protest, using material from LSE’s archive (and an overhead projector) to tell the story.

What really struck me about the show was the form they’d chosen to tell the story, the way audience members were invited to speak certain lines, though only after checking beforehand that we were comfortable being asked to speak. The space, a small former locker room in the Summerhall basement, was imbued with the spirit of a student meeting hall with orange squash and biscuits on offer. There was a real sense of this being a collective endeavour, something shared.

Rees and Uboldi explore how the students organised and mobilised and find ways to connect the story they are telling with the place we are now politically. They also talk about their own experiences as young artists living in grotty, cramped, and potentially unsafe accommodation in London, and Uboldi describes how it feels to be a young queer migrant, how the life he has in the UK differs between the one he might have had in Italy. The way they knit the personal and political is so clever and delicate and lovely, and the show never loses sight of why they decided to tell this story and what we can learn from the protest movements of the past.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, or want to tell me about your fringe show, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

Of course if Johnny and The Baptists had applied to the Arts Council for money to do The Tempest, they would certainly have been turned down.