Edinburgh Fringe round-up: My Mother's Funeral: The Show, Divine Invention and Sh!t Theatre: Or What's Left of Us

On a trio of shows exploring different aspects of grief, loss - and love.

I’ve been in Edinburgh for almost a week and by the time this goes out will have seen somewhere around 25 shows at the Edinburgh International Festival and the Fringe (which is why this week’s edition is a little late arriving in your inboxes). I haven’t even scratched the surface of this enormous festival, though I have been caught in the rain twice, and am currently getting by mainly on coffee and snatched snacks. The sense of being in a bubble has been intensified by the rest of the UK seemingly being intent on tearing itself in two; never has the fringe felt further away from the real world than this year. It is very discombobulating and all too easy to tune it all out as you dash from show to show.

Along with my colleagues at The Stage I’ve been filing a steady stream of reviews since last Friday. For the next few weeks, I’ll be using this newsletter to explore the work I see here in a more thematic way.

If you enjoy reading this, then please share with others you think might feel likewise. Café Europa is free and I’m keen to keep it that way, but if you’d like to help sustain it, support my writing (and receive the occasional bonus edition - like this one on Carolina Bianchi’s The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella), please consider becoming a paid supporter.

My Mother’s Funeral: The Show, Roundabout@Summerhall

The Roundabout is a pop-up in-the-round venue, a transportable theatre that can be set up anywhere. Created by new writing company Paines Plough, for the past 10 years it has travelled the UK, but every August, you can find it in the courtyard in Summerhall, the former veterinary college-turned-arts-centre.

The theatre seats around 160 and, inside, it kind of feels like a space capsule with its glittering LED ceiling. The nature of the space lends itself to certain kinds of work. It’s incredibly intimate with the audience seated around the performers, but not a space where you could place elaborate set. For this reason, it tends to programme solo shows and two-or-three handers. Duncan Macmillan’s all-conquering Lungs started out in the Roundabout and is the epitome of the Roundabout play.

This year one of the highlights of the Roundabout programme is My Mother’s Funeral: The Show, by Kelly Jones, a play about the twin impact of losing someone, the emotional and the financial.

The play starts out as a satire, taking swipes at the theatre industry and how under all the talk of diversity and inclusion there’s often a very narrow band of stories that working class artists are permitted to tell. The doors of intuitions are open but only if you’re willing to use your background as fodder. The literary manager in Jones’ play makes all the right supportive noises about her work but, really, he wants her to deliver a council estate story, the grimmer the better, a play that will let the audience pat themselves on the back for watching before heading off to their no doubt more comfortable homes. Abigail is not interested in writing that kind of work but then her mother dies suddenly, and she finds herself facing costs beyond what she can afford. She doesn’t want her mum to have a council burial, so she offers to write a properly raw and gritty play about what happens when you lose a parent and there’s no money.

While the comedy, at least in the first half, is quite broad, it speaks to a truth about the theatre industry and the relationship it has with authenticity. (Holly Beasley-Garrigan’s 2019 show Opal Fruits as also explored the pressure that artists from working class backgrounds can feel to mine their lives for art).

If Jones’ play was content only to do this, it would still a necessary rebuke to a culture that seemingly only values certain voices if they tell certain stories. However, it gradually shifts into a more nuanced portrait of grief. Abigail is so stressed about money that she can’t grieve properly whereas her brother can’t grieve because he believes he was always secondary in his mother’s eyes. His relationship with her was chilly and now he doesn’t know how to feel. They’re both stuck, emotionally, while their mother’s body is still in the hospital waiting to be claimed. Debra Baker as the mother who lives on in their memories really anchors the show, drawing out the warmth in the writing. Director Charlotte Bennett really understanding how to make the most of the Roundabout space and the last section of the play knits together these two aspects of the text – the satire and the family drama - in a very dynamic and ultimately very moving way.

Divine Invention, Summerhall

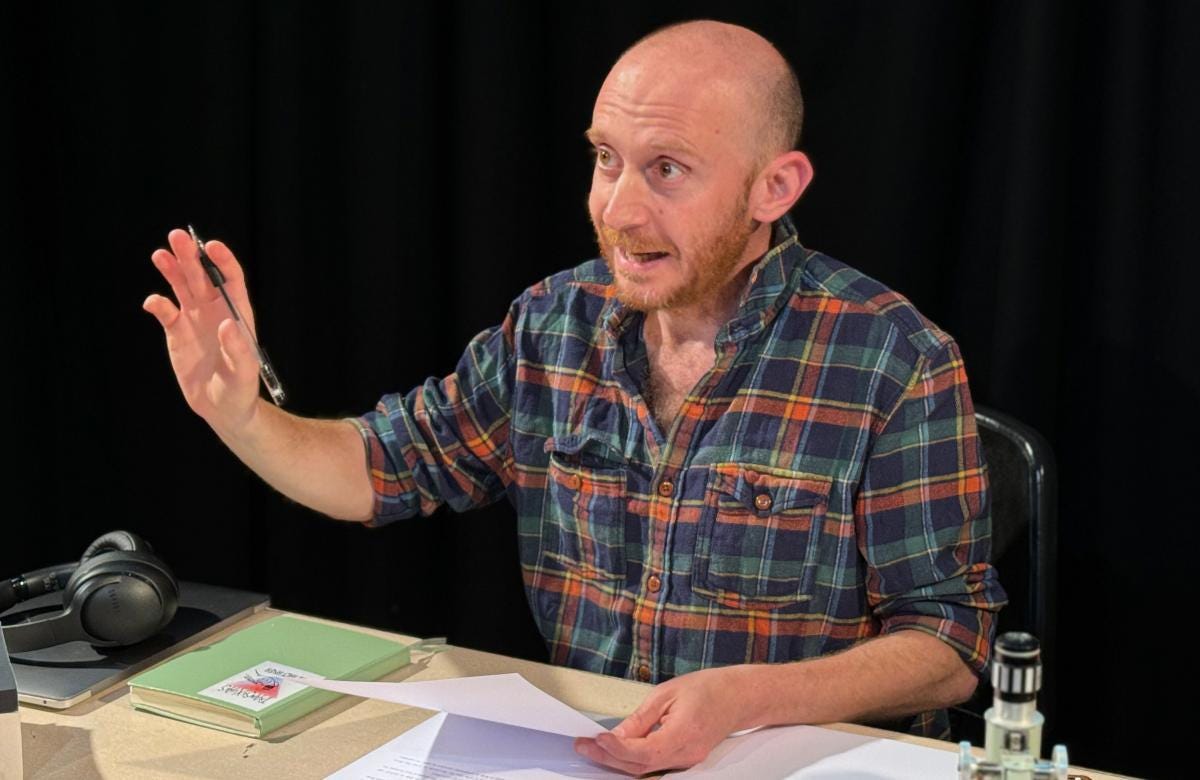

The term lecture-theatre is a term you encounter a lot on the fringe, but while you could apply it to Divine Invention, by the Franco-Uruguayan playwright Sergio Blanco, I think essay theatre might be more accurate. Though, actually no, that’s not quite right either. Blanco uses the term ‘auto-fictional conference,’ something that is part memoir, part meditation on love, though death also plays a significant role in this complex layered text delivered by Daniel Goldman, Bianco’s regular collaborator (though usually in a directorial capacity and not as a performer) and translator.

Goldman was the founding artistic director of CASA Latin American Theatre Festival which he ran between 2007 and 2019, and has worked on a number of Blanco’s plays in the UK, including Thebes Land and, most recently, When You Pass Over Me Tomb, a text which explored mortality and desire (and even necrophilia).

Goldman sits at the desk covered in items, a microscope, a Superman comic book, a rib bone, the printed text in front of him. The text itself is subtitled ‘The Celebration of Love’ and broken down into 30 sections, fragments perhaps. Goldman recites these. Each fragment contains a memory or an idea. Blanco will often refer to studies he has encountered, to scientific discoveries about what happens to us cognitively when we fall in love.

He talks about the artist Francis Bacon, whose lover and muse George Dyer overdosed in a hotel room, on the eve of the artist’s retrospective. He talks about his own sexual awakening, his dawning attraction towards a boy in a boxing club, the bodily quality of their love, the silent fucking in the shower stalls.

It’s also, by virtue of being auto-fictional, a text about being a writer, the various projects and places Blanco finds himself in. It’s a text about what it is to fall in love with a city.

The text is peppered with quotes, like Fernando Pessoa’s reflection that “love is mortal demonstration of immortality.” It is at times like having access to someone’s library or the inside of their head, with the text veering down different synaptic avenues. Some of the most beautiful and striking passages are about death and its intersection with life. Blanco lists figures from history and literature who have ended their life for love. He describes the first corpse he ever encountered. The most moving moment for me is when Blanco recalls the anthropologist Margaret Mead’s observation that an ancient, healed femur bone marks the start of civilisation because it means someone must have loved that person to have watched over them and cared for them while they recovered.

Goldman delivers all this in a gentle, measured way, a compelling presence sitting at his desk. This is a play that invites you to listen. It requires your attention. It is a very still and quiet, but in a place as overwhelming as Edinburgh during the fringe, this stillness is not just welcome but necessary.

Sh!t Theatre: Or What’s Left of Us, Summerhall

Sh!t Theatre have long been one of my favourite UK companies. Their work is superficially scrappy but actually incredibly well-crafted and politically potent. Their 2016 show Letters to Windsor House remains one of the best pieces I’ve ever seen on the precarity of renting in London. (They basically used the mail addressed to former tenants that arrived at their shared flat to explore the instability of life in a big city, and they did so while dressed up as cardboard post-boxes and singing songs about adult diapers).

In 2019’s Sh!t Theatre Drink Rum with Expats they turned their attention to Malta and made a piece about the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean and political corruption. Underneath the silliness, sea shanties and copious quantities of rum, there was a seam of hard, bright anger running through. It was raucous and funny and daft and anarchic and excellent.

Drinking and singing are recurring elements in Rebecca Biscuit and Louise Mothersole’s work, something true of their latest piece, Or What’s Left of Us, their first at the fringe in some time. It’s a show about folk music, on one level, about them starting to explore the UK folk scene, getting off their tits at folk festivals and going to various folk clubs, including one in Yorkshire which was firebombed after their visit. Who would firebomb a folk club, they wonder?

They sing a lot of traditional songs during the show. They sing John Barleycorn, a celebration of the grain from which beer is made, and they sing the Scottish folk song Parting Glass, the song you sing at the end of an evening to send people on their way. They got into folk, they explain, because they needed an outlet, a way of creating together, making something together, at a time of turbulence in their lives. Folk songs are often about death, they are containers for pain and people have been singing them for centuries. Folk felt like a good fit.

Instead of their usual white face paint they are costumed like residents of Summerisle and sport streaks of black beneath their eyes as if they have been weeping. As in all their work, there is a show is a thing of real craft. As ever what appears a little slapdash and reveals itself to be elegantly structured. There are call-backs and punchlines to previously seeded jokes. There is a recuring motif about those Japanese bowls that have been broken and pieced back together, whole but not unmarked. There is also pain, controlled, but always present, always there.

The beauty of the singing (which is beautiful) is increasingly punctured by flashes of red light as folk music giving way to folk horror. The last 10 minutes are absolutely brutal, as honest and raw as it gets, as they address head-on the losses they have suffered, the loss of Louise’s father, and Becca’s partner, Adam Brace, who was also their creative collaborator, their director (or ‘directurg’ as he was sometimes credited). Adam was not someone I knew well, but he was someone I was always pleased to see, and I looked forward to our annual pint(s) in the Summerhall courtyard. He was, I think, one of the first people I interviewed for Exeunt, when he was making work with Simple8. (The interview is a little drily written and doesn’t include his digression about being drunk in the Hogarth Museum, better to read this lovely profile of him here in The Stage). His fingerprints are still everywhere at the fringe, in the work of other artists he helped shape, his shadow is long, and this show is an incredible memorial and purge and celebration all wrapped into one; it is, as they said, a kind of wake in the form of a theatre show.

Normally after the show, they invite people to sing with them in the bar but, on the day I see the show, there was a private event going on (thank you National Theatre of Scotland) so I just sort of walked around feeling dazed and had a little weep in the street. The show sort of unlocked something in me. I thought about Adam, of course, but also about the uncle who died two years and a day ago and of whom I was very fond, and other people who are gone (and then I went and drank quite a lot of wine). Because while it’s show about their grief, it also makes space for everyone’s grief and is big enough to hold it. It doesn’t hide from the horror of their losses, but like those folks songs, it makes a space to put that pain – and share it.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, or want to tell me about your fringe show, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

Or What's Left of Us and My Mother's Funeral are easily in my top 5 as well so far - I saw them both in the same day and had SO many feelings! I can't wait to check out Divine Intervention as well.