Bohemian rhapsody: Jeff James' virtual reality retelling of The Winter's Tale

On what happens when you fuse Shakespeare's 'problem' play with the world of online gaming.

Earlier this year, I spoke to director Jeff James about his new production for Latvia’s Dailes Theatre, a pretty radical reworking/rewriting of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale relocated to Silicon Valley. Last weekend, I finally got a chance to visit Riga and see the production for myself, more on which below.

Café Europa is free to read and it’s important to me that it stays that way, but it takes time to research and write, so if you find it valuable and would like to help support my writing, you can do so by becoming a paid subscriber or you can share it with others who might like it. Or just hit the ‘like’ button. Everything helps.

“The wearing of virtual reality headsets during take-off and landing is not allowed.” This was how the safety announcement concluded on my return flight from Riga. I don’t know about you but this was a new one on me. Are people really wearing VR headsets on planes in such numbers that such an announcement is necessary? Personally I don’t even like to listen to music. I need to be alert to every little blip and judder, but I can understand why some people might want to immerse themselves in another world while crammed in a metal tube hurtling through the air.

The possibilities of virtual reality and immersive gaming form the core of Jeff James’ - very - free adaptation of Shakespeare's The Winter’s Tale for the Dailes Theatre in Riga. Housed in a blocky 1960s building with a main hall capable of seating up to 980, the Dailes Theatre is the largest professional theatre in the Baltic region. The repertoire has a decidedly Anglophile bent, featuring work by Alistair McDowall, Lucy Prebble, Duncan Macmillan (Lungs, inevitably), Dennis Kelly and a production of Stoppard’s Leopoldstadt directed by John Malkovich as well as Mischief Theatre’s comedy The Play that Goes Wrong. It’s also the producer of Lukasz Twarkowski’s Rotkho, one of the hottest tickets on the European festival circuit. It’s big stage with a large ensemble and considerable resources; so, basically, a gift to a director.

A regular associate director of Ivo Van Hove, most recently on A Little Life in the West End, James made a splash in the UK with an adaptation of Jane Austen's Persuasion that saw the actors frolicking through banks of foam, while his adaptation of Sophocles’ Philoctetes, retitled Stinkfoot, for London’s Yard Theatre featured gallons of treacle - molasses actually – and several three-bar heaters, with predictable olfactory effects. While there are no foam or fluids in his Winter's Tale, it’s far from a conventional adaptation, rather a complete rewriting of the play, in which Leontes is now tech billionaire Leo Winter. As the writers of Succession, among others, are always telling us, media moguls and tech billionaires are our equivalent of kings.

Winter is the CEO of AppZapp, a company which makes an advanced form of virtual reality tech. The only problem is their new game, Bohemia, feels so real that some people’s brains can't handle it. If you die in the game, there's a small chance you'll expire in real life (bear attacks are proving to be particularly lethal). Children seem immune to this potentially catastrophic bug - something to do with brain plasticity - and so instead of calling a halt to the launch, they decide to age-restrict it and market it to the under-21s, creating a virtual space that no adult can enter (can’t see anything going wrong there). Leo describes it as: “A magical walled garden in which our children can play.”

Winter has other things on his mind aside from his product launch. He's convinced himself that his pregnant wife Hermione has cheated on him with company co-director Paul and that the child she's carrying is not his. Even a DNA test won't convince him otherwise. He remains unshakeable in his belief. There are obvious parallels with Steve Jobs here, who refused to acknowledge his daughter he had with his first wife was his for years, not to mention Elon Musk and his fellow pro-natalists’ unhealthy obsession with their genetic line. James captures how the self-belief that enables someone to become a tech visionary often walks hand in hand with a deep need to exert control over everything, even the mess and risk of procreating. Even when Leo is presented with his new-born daughter Rose (played by one of four real-life babies), he remains, not just unmoved but repelled by her and orders his friend Ant to “make her disappear”.

Despite the Silicon Valley setting, the plot thus far elegantly mirrors that of Shakespeare (albeit with some embellishments, including an opening scene where a heavily pregnant Hermione uses an AppZapp headset to help her masturbate).

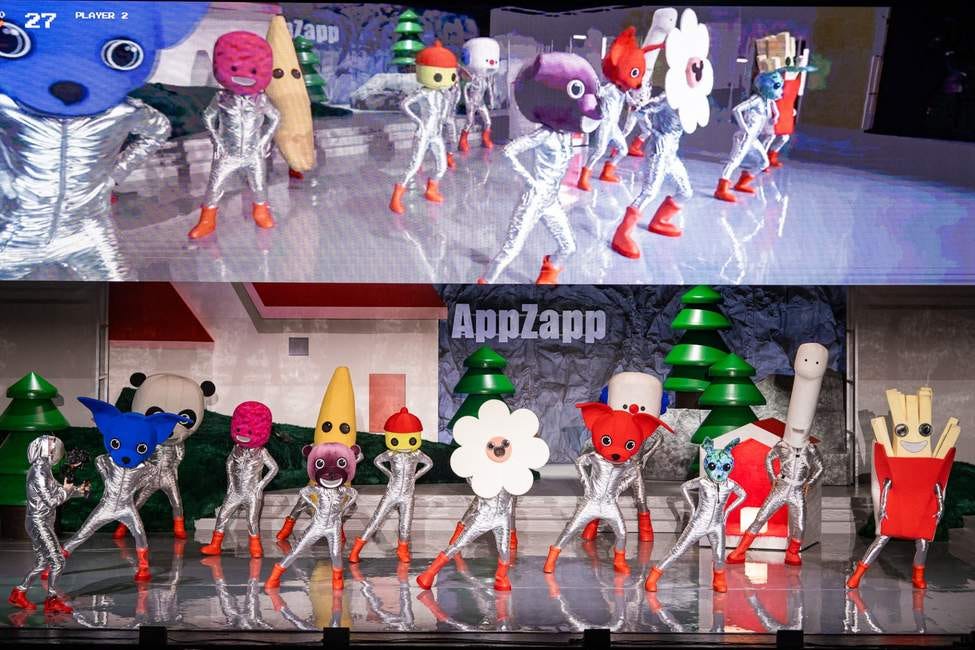

But all this is really build-up for the moment we enter Bohemia. This is proper coup de theatre, a real ‘We're Not in Kansas Anymore’ moment. A massive digital screen descends from above like a safety curtain. A title screen flashes up and we get our first glimpse of the in-game world as Ant decides to hide baby Rose in the digital realm, somewhere she can grow up in safety.

The passing of 16 years is marked by actor Indra Briķe as Time, speaking the only passage lifted directly from Shakespeare, Brike performed in the role of Hermione at the Dailes Theatre three decades ago. As she speaks her face is gradually digitally de-aged. This is a technique Van Hove has used too, digitally ageing Gillian Anderson in his stylish, if mirthless take on All About Eve, but whereas that made me want to throw things at the stage in frustration, here it's used to more striking and poignant effect.

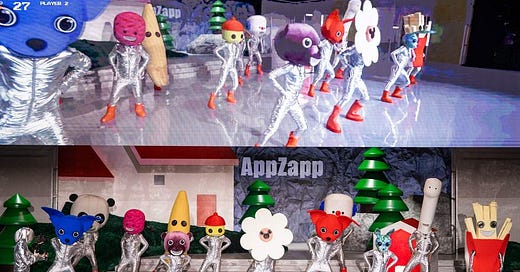

James sets Shakespeare’s pastoral scenes inside the game. Rosanna Vize’s vivid, poppy set with its fur-lined houses and fake plastic trees that look like oversize Lego pieces, a cross between the set of a kids’ TV show and the office of a particularly wanky Soho ad agency, comes into its own, as the backdrop to this multiplayer role-playing game, a sort of Second Life with an 8-bit aesthetic.

The performers wear silver jumpsuits that look like they are made out of space blankets, chunky orange boots and bulky avatar heads shaped like animals - bears (obvs) and bunnies - Lego-like humanoids or, in one case, a banana (costumes also by Vize). The cast perform behind the massive screen - we can only see their feet - while their image is projected on the screen and overlaid with graphics. (Somewhat wonderfully, the back of the video screen becomes a stand-in for the night sky, the blinking connections constellations). Deploying a limited range of movements, the characters communicate primarily via a kind of gestural emoji language. When they are sad, they rub their eyes as the word ‘crying’ appears on screen. When they are surprised, they raise their hands to their faces as the word ‘shock’ pops up. All the in-game interactions take place in this way. (Here’s an interesting piece on how our brains process emojis, which argues they aren’t debasing language, rather they’re enhancing it). There’s something kind of audacious in the way it distils Shakespeare into this kind of digital shorthand, gutting the play of poetry. James has argued that Shakespeare’s language is alienating, and that translating it into a more contemporary form of communication, will allow the audience to correct more directly with the themes of the play.

I’m not sure I wholly buy this but at the same time I can’t help but admire the way James has napped the play onto his game world, a space where people can roam around in disguise and assume other identities. Some of the parallels James has created are ingenious. Here Clown, the slightly dim Young Shepherd, is an unworldly kid who falls for a scam by ‘a Nigerian prince’ with an inheritance he can only access if some generous person transfers some money into his account. Rose, who knows nothing of the world, falls for Flinn, the son of Leo’s rival Paul, who uses the game as a place of escape from his parents. The play raises a lot of interesting questions about the nature of online relationships. Can you form a genuine connection with someone without ever meeting in the real world? Can you fall in love? Does an in-game kiss count as cheating? And what about friendships? Can you find your people there? Watching it I was reminded of this moving article in the Times about a young man with a degenerative condition who lived a rich other life inside World of Warcraft.

At times it also put me in mind of Gabrielle Zevin’s novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, in which the grieving game designer protagonist loses herself in the world of one of her creations following the death of her husband, as well as The Truman Show in terms of how it explores Rose’s growing realisation that her world has limits, and that she has the power to exit it if she wishes. Because her whole life has taken place inside the game, she has little conception of who she might be on the outside; she worries she may not even be real.

Like the source material this is a play of two halves, one part tragedy, one part colourful romp. The Bohemia sequence requires a lot of expositional legwork to set up and the early scenes of an increasingly belligerent Leo torpedoing his own life can feel a little theatrically flat at times, though this is perhaps necessary to create a tonal contrast with what comes later.

Because the production devotes so much time to explaining how the game world works, it also opens itself up to nit-picking. Despite the adults-only rule it seems remarkably easy to infiltrate Bohemia as a grown up. You just have to lie about your date of birth - and to be sanguine about potential bear attacks, I guess - and you’re in. AppZapp must spend a fucking fortune on lawyers. James also glosses over how it is physically possible for Rose to live in the game. There’s a brief mention of nutrient vats, which brings to mind some kind of Matrix style goo-pod, but the production, perhaps wisely, declines to elaborate on how this works.

Instead, it focuses on Rose’s deepening existential questions, her need to know herself and where she came from. Madara Viļčuka does an amazing job of constructing a character while sporting a plush purple bear head. The whole cast do well in executing the stylised in-game movements while wearing what are presumably oppressively sweaty costumes.

James also finds a clever and bittersweet way of showing Leo coming to terms with the pain he caused (and dealing with the whole statue thing). But while the play does not let him off the hook, it still centres him at the end. While this is in keeping with the original, the fact that Leo seems pretty willing to let his daughter die at one point, means I honestly couldn’t bring myself to care all that much about his distress. As Leo, Mārtiņš Meiers does an admirable job of conveying just how broken he has been by his actions, but given how willing James has been to deviate from the text up until this point, I would have like to see much more of a focus on how Rose copes emotionally with meeting the father who disowned her, not to mention the whole figuring-out-how-to function-in-the-world thing. If you’ve gone so far, why not go further?

In equal measure smart and daft – it even includes a jig to Beyonce’s ‘Texas Hold ‘Em; – Jeff James production might not wholly succeed in making you empathise with a billionaire, but it is slick, accessible and funny, and raises some interesting questions about lives lived online. If it ultimately suffers a little from cleaving too close to the source - lopsided structure, divisive ending and all - it’s hard not to admire its playful approach and sense of invention.

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days

The Flock – Inspired by Thom van Dooren's book The Wake of Crows: Living and Dying in Shared Worlds, the new devised piece by Žiga Divjak will explore themes of migration, integration and ecological collapse. It opens at Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana on 16th October

Six Against Turkey – Kosovo’s chief provocateur Jeton Neziraj’s new play draws on real event in which six men were extradited to Turkey from Kosovo as possible plotters following the coup of 2015. Drawing on Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes and deploying traditional puppetry, the show is directed by regular collaborator Blerta Neziraj and the premiere takes place at the ODA Theatre in Prishtina on 16th October.

The Martian Chronicles - French theatre-maker Philippe Quesne’s new show draws on Ray Bradbury's 1950 collection of short stories imagining an American society setting up home on Mars in the aftermath of a nuclear war. It premieres in Basel Theatre in Switzerland on 16th October.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com