Ripping up the rule book: Jeff James' radical reworking of The Winter's Tale

On a bold, Silicon Valley reimagining of Shakespeare's play in Latvia.

Hello and welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

This week I’m in Vienna for the Wiener Festwochen, one of Europe’s biggest cultural festivals and the first under the artistic directorship of Milo Rau. Here’s my review in The Stage of Kirill Serebrennikov’s Barocco, a fusion of opera and images of protest and resistance. I’ll be exploring some of the other work I saw in later newsletters.

Fans of folk horror fans might be interested in this piece I wrote for BBC Culture on Robin Redbreast, a creepy BBC Play for Today from the 1970s which is the inspiration behind an unsettling new show by actor Maxine Peake. It’s a real curio, combining elements of Rosemary’s Baby and The Wicker Man, the latter of which it predates, and I can see why Peake wanted to do something with it.

Before I hopped on my bus to Vienna, I had the opportunity to chat to director Jeff James on tearing apart Shakespeare’s plays, working with Ivo van Hove, his radical reworking of The Winter’s Tale for the Dailes Theatre in Latvia, and that one time he was accidentally responsible for a rat infestation.

If you find this newsletter interesting or valuable, please do share with those you think will feel similarly, or consider becoming a paid supporter. It’s a total joy to write, but takes a lot of work. I recognise times are tight, so I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to support my writing this way. I am aiming to keep as much of this newsletter free to read as possible, but there will be sporadic regular bonus editions for paid subscribers.

“There’s no fluids in this one,” laughs Jeff James. The director rose to prominence in the UK with a version of Jane Austen’s Persuasion in which the characters frolicked through banks of foam. His new adaptation of The Winter’s Tale, which opens this week in the Dailes Theatre in Riga, shares a similar approach to its source material -though without the bubbly stuff.

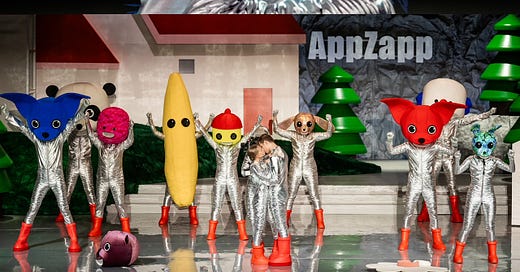

James has transplanted Shakespeare’s play into the world of tech billionaires. Leo Winter is the CEO of AppZapp, the California tech company behind Bohemia, a metaverse-style digital realm which you can only enter if you’re under the age of 21. No adults allowed.

When Leo becomes paranoid that his business partner Paul is the real father of his child, his jealousy escalates and there are consequences for everyone involved.

The Winter’s Tale is a play James has directed before, back in 2019, but coming to it again, now as a father himself, he found his relationship with, and understanding of, the play had shifted. Elements of the play, he says, “resonated with my personal experiences as a parent today.” The key difference is that Leontes is a king, a man of great power. To find an equivalent level of power today he had to look to the tech sector. “The man-child ego of Leontes maps quite well on to an Elon Musk kind of figure,” he explains.

Working in Europe gives him greater freedom to deviate from the text (the production is, tellingly, billed as being ‘After Shakespeare’). Since it’s being performed in Latvian, he says, there is already a process of translation in place. “I used that as an encouragement to myself to do a more radical transformation,” he says.

In fact there’s just one passage of Shakespeare’s verse in his version, the speech given by Time at the point in the play when Shakespeare took the formally bold move to move the story forward in time by 16 years. Time, in his production, will be played a renowned Latvian actor Indra Briķe, who played Hermione in the last significant production of The Winter's Tale in Latvia.

Untethered to language, he focused on the structure of the play, trying to “understand the structure of the original play at the deepest level possible.” He’d love to do something similarly bold in the UK, but to depart so radically from the text “would be illegal at the moment in British theatre.”

While there’s no foam, there will be a huge LED wall that covers the stage “so you're only experiencing it through video.” This will create an alienation effect, but he would argue, listening to a play in Shakespearean verse is “the ultimate alienation effect.” James enjoys working with Shakespeare in the original language, but “that's not the only way to do these plays.” In Riga, he’s really enjoyed being able to “rip up the rulebook.”

“Muscular interventions”

My first encounter of James’ work was Stink Foot, at the Yard Theatre in London (a venue I’ve written about previously here) back in 2014, a reworking of Philoctetes in which he deployed a huge amount of what looked like treacle, though actually it turns out they used molasses. “We got sponsored by Tate and Lyle and we had to go there in a van and collect 125 kilogrammes of molasses. It’s essentially the same as treacle, but it’s a waste product, which they can't sell so they were happy to give it to us.” The actors ended up coated in sticky brown goop - a stand-in for rotting flesh - with a three-bar heater, shall we say, intensifying the sensory effect. “The Yard got infested by rats,” he says sheepishly.

On a very basic level, when you fill the stage with foam - or molasses - it changes how the actors engage with the space. In Winter’s Tale, a play which features a big shift in tone from tragedy to comedy at the midway point, there won’t be any sticky stuff, but there will be that massive LED screen plus an array of avatar heads. “I think those kind of muscular interventions are really useful and really fun,” he says.

James’ taste in theatre was shaped in part by the Young Vic in London. While participating in their directors’ programme, he met the then artistic director David Lan, and the director Joe Hill-Gibbins. “They were talking about all this cool stuff that was happening in Germany,” James said. This was before Sebastian Nübling’s Three Kingdoms had exposed a generation to the German approach to theatre (the impact this show had on those who saw it is something I explored in this previous edition). “I think the London stage at that point was pretty resistant to more expressionistic forms of theatre,” he says.

“Totally mind-blowing.”

James was excited by the kind of stuff Lan and Hill-Gibbins were talking about, so he went to Berlin for a week and immersed himself in theatre. He saw Thomas Ostermeier’s famous production of Hamlet and Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller’s production of John Gabriel Borkman at the Volksbühne where the actors were “all wearing kind of rubber faces like in Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” He neglected to check the run time. It turned out to be 12 hours long. “I left at 4am,” he says, slightly regretfully.

“That trip was life changing,” he says. “Totally mind-blowing.” Not speaking German well meant he really focused on the imagery, on what was happening on stage and less on what was being said. “That was a very useful training in thinking about how meaning is created without text.”

The Young Vic organised some more trips, to Poland and to Germany, for the young directors, including one to Munich Rezidenztheater that the director Rikki Henry, now making a name for himself on the German-theatre scene (and who I interviewed recently), also went on. Eventually James got a job as an intern director – like “an assistant-assistant director”, he explains – in Munich and gained more of “an understanding of how a repertory company worked and how the European rehearsal model worked.” Crucially he got to further immerse himself in German theatre. “I saw something like 60 shows.”

It was while he was in Munich that he first met Ivo van Hove. He was rehearsing a show in town and James, on discovering this, essentially “truanted out of the rehearsal space I was supposed to be in and sat in those rehearsals for a couple of weeks.” Later when Van Hove was looking for an assistant for his production of A View from the Bridge at the Young Vic, James got the job. He’s worked regularly with Van Hove ever since, and has been associate director on seven of Van Hove’s productions including his monster hit A View from the Bridge and Hedda Gabler.

What he enjoys about working with Van Hove – apart from his “life-friendly” rehearsal schedule - is that “he doesn't really mind where solutions come from and he's not precious about his relationships with the actors.” If his associate director comes up with something that works in the situation, that’s fine with him. “A lot of directors are anxious about all the ideas coming from them,” he says, but Ivo’s not like that. He ended up recreating A View from the Bridge in Van Hove’s absence several times over the years. Getting to know that show so intimately has “been really useful for me, as a director.”

As much as he enjoys working with Van Hove, eventually James had to find a way to “prioritise my work.” Though he did end up working with him again on the West End production of A Little Life, based on the novel by Hanya Yanagihara. “There was a sense that they were really proud of this show and really excited to take it to a British audience.”

“Ivo just jumps in and works through a play,” he says of the director’s working method. “There isn't really any exercises of character building. Everything comes out of the text, which I think is why the work is so clean and pure. And also, why it is so successful. His shows are very well made, because the time is spent on making the shows.”

His production of Persuasion – the one with all the foam - which he adapted with James Yeatman, opened at the Royal Exchange in Manchester in 2017. It was described by critics as “ruthlessly 21st century.” The word ‘irreverent’ cropped up in a lot of the reviews. When talking about his adaptation process, he described it in quite violent terms. “When you adapt a novel for the stage you have to beat the novel up, you have to hack away at it, cut it up and change it,” he said in this interview with Lyn Gardner.

Last year he directed Nina Segal’s similarly free adaptation of Ibsen, Shooting Hedda Gabler, a co-production between the Rose Theatre in Kingston and the Norwegian Ibsen Company, in which a former child star makes a movie version of Hedda with an imposing, controlling director called Henrik. The Guardian called it “a piercing, stylish reinvention of Ibsen’s classic.”

Now he’s getting to experience the European model of making work first hand. The Dailes Theatre has a permanent ensemble of 40 actors. At the start of the creative process, the general manager told him to use as many actors as he wanted. His production of Winter’s Tale features 15 people. “For totally understandable reasons, the conversation in the UK always goes the opposite way,” he says. “It’s always: could we do it with four actors or three actors or no actors.”

He was worried that, as an outsider, the ensemble might be a bit resistant, but he says, “the actors have been totally committed, really engaged with the project and have been brilliant, brilliant collaborators, actually.” The pay is also significantly better than it would be in the UK, he adds. “I’m basically being paid four times what I would get paid in the UK to do this show,” he says, echoing something that Swedish director Maria Aberg also raised when I spoke to her recently, on the difficulty of sustaining a career as a director in the UK.

James also feels that the UK theatre scene remains resistant to the kind of work David Lan was programming when he was at the Young Vic, though “unlike Rufus Wainwright, I don't think any of it is to do with Brexit.” Rather, James thinks, a formal conservatism still prevails. “There's like a long-held suspicion of formally experimental work,” he says, and there’s still an overwhelming interest in naturalism. Not that there’s anything wrong with naturalism, he clarifies, but when “it’s done in a lazy way, as it often seems to be, it is totally pointless.”

Working in Riga also affords him the opportunity to make work of scale that simply wouldn’t be possible in the UK. “If I could work make work at this scale in London, I would be very happy to do so,” he says, “but it’s not really feasible.”

While working outside of the UK for so many weeks has not been undisruptive to his life, especially with a young family, he says, “having been such a European theatre fanboy, to actually be out here, making a show with a repertory company, is thrilling.”

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days.

Bergen International Arts Festival – The Norwegian international cross-arts festival opens with a production of Peer Gynt starring Herbert Nordrum from the Oscar-nominated film The Worst Person in the World, alongside the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra. Work by Tim Crouch and Acosta Danza will in also feature in the festival which runs from 22nd May – 5th June

Kunstenfestivaldesarts – The Brussels-based festival of contemporary theatre, dance and performance started on 10th May and runs up until 1st June. Highlights of the coming week include Łukasz Twarkowski’s Respublika (which I am desperate to see) and a collaboration between choreographer Marlene Monteiro Freitas and Sevillian dancer Israel Galván.

Prague Fringe – This six-day fringe festival showcases hundreds of artists from all over the world in spaces across Prague’s Malá Strana district. Featuring a mix of theatre and comedy, and featuring everything from Ukrainian improv to Czech comedy to a Finnish show about spanking, this Edinburgh Fringe in miniature runs from 27th May until 1st June.

Thank you for reading! You can contact me about anything newsletter-related on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

Great post Natasha! Makes me want to buy a plane ticket and just wander from festival to festival to see all these incredible productions!! Tim Crouch! I did a performance of An Oak Tree with him.