What comes next? Negotiating Peace and the plays of Jeton Neziraj

On a new play from Kosovo grappling with the peace-making process.

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

I’m currently in Kosovo, where I arrived last week for the premiere of Negotiating Peace - of which more below - mainlining one euro macchiatos and prepping for the workshop on criticism which is held with young writers in the region every year.

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, or find it helpful, then please consider sharing it with friends or colleagues or, you know, anyone who might find it useful. Please also consider becoming a paid supporter, as it really makes a difference and will allow me to expand my coverage. As is the way these days, I also have a Ko-fi account. I want to keep as much of the content free as possible, so all donations are very welcome.

Negotiating Peace

The panda was a surprise. Of all the things I expected to encounter in a play called Negotiating Peace written by a prominent Kosovar playwright, a man-sized panda, of the kind that kids have their pictures taken with in the streets, with the little whirring internal fans designed to stop the poor sap inside from keeling over, was not on the list.

But then Jeton Neziraj, and his regular director and collaborator Blerta Neziraj, thrive on bold gestures designed to make the audience sit up in their seats. Their work is often provocative and frequently irreverent but also driven by principle and a willingness to confront hypocrisy both domestic and global.

Negotiating Peace explores the process of diplomacy through which peace is brokered, the people sent to make that peace and the tactics they deploy. It takes its main inspiration from To End a War, a 1998 memoir by the American diplomat Richard Holbrooke, which documents his role in bringing together the Dayton Agreement of 1995 that ended the Bosnian War. It also draws from Ismail Kadare’s novel The General of the Dead Army, about a general searching for the remains of his dead countrymen.

This is not documentary theatre. Audiences will not get a straightforward account of how Dayton was negotiated. Instead, we are presented with a bleak comedy about the act of hashing out the fate of nations behind closed doors that sits at the midpoint between fable and satire.

Two negotiators, Madera, from the Republic of Banovina and Daniella, from Republic of Unmikistan, come together to try and reach an agreement about the contested Green Valley under the eyes of a Joe Robertson, the American emissary to the UN and the Holbrooke stand-in, General Amadeus, the only one present to have seen combat, and Maria, a civil society activist (and the butt of many of the jokes).

While it shares some DNA with Oslo - J T Rogers’ 2016 dramatization of the negotiations that led to the 1990s Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, which UK audiences saw at National Theatre in 2017 - it’s tonally a very different animal. There are dance sequences and dream sequences and did I mention the panda?

Neziraj’s work highlights absurdity and hypocrisy through amplification. We see the negotiators fret over protocol and bicker over the position of the chairs in the negotiating room in a way that feels at once exaggerated but also plausible. While Neziraj deals more in types than in characters, he captures the interplay of egos in the room, the pettiness and self-aggrandisement. Through extensive use of live video feeds, the play captures the scrutiny they are under. It also shows the downtime, the after-hours drinking, and the flashes of humanity beneath the professional veneer.

Polish designer Agata Skwarczyńska’s set consists of a round table, that while simple still manages to evoke Doctor Strangelove. Around this table, the negotiators debate the naming of streets (should a street that honours a war criminal be renamed Jim Carrey Street?) and sketch out a demilitarized zone on a napkin. They speculate that people are purposefully making noise outside to keep them from sleep. Madera argues that “peace negotiations are the essence of war, it's all that's left in the end … like an extension of the war,”

“Peace only becomes important to you when your fear of the refugees takes over, Daniella – played by Bosnian actor Ejla Bavcic - later accuses the American Joe Robertson, played by Norway’s Harald Thompson Rosentrom.

So much that seems extreme is inspired by or a reference to something that did happen, either in Dayton (as this Guardian archive piece illustrates) or around some similar table.

One of the production’s more interesting decisions is to make space for someone with their own personal experience of war and its resolution to speak within the frame of the show. On the night of the premiere, it was veteran Bosnian journalist Aida Cerkez, who shared her experience of Sarajevo under siege and the moment when, in her hotel room, she first heard there was peace. She concluded by singing the song she used to sing to distract herself as she drove her car up the road exposed to snipers’ bullets. Her testimony was incredibly powerful and the show is structured to allow different people to speak of their experiences during the tour.

It sounds obvious, but there’s a difference between making a play for people who have lived through war and one designed to contextualise things for an international audience. Again and again Neziraj uses humour to speak of the unspeakable, like the fact that during the Bosnian war, it is said that some wealthy foreigners paid large sums of money to act as snipers and shoot at civilians (the horrific topic of the documentary Safari Sarajevo).

For all that Jeton Neziraj and Blerta Neziraj delight in absurdism and surreal imagery, in weird interludes where the cast caper about in fetish gear and in jokes about people pissing their pants, the cold reality of war - the atrocities, the dead, the missing, the raped - is never forgotten. It underscores everything.

A pan-European approach to theatre-making

The Negotiating Peace creative team consisted of people from Kosovo, Ukraine, Serbia, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Italy, Czech Republic, Albania, North Macedonia, Norway, Poland and Estonia. (You can read more about this process in Nick Awde’s feature for SEEstage).

This is just the latest step in Qendra Multimedia’s increasing internationalisation of their work. In 2021, they co-produced Balkan Bordello, Jeton Neziraj’s take on the Oresteia, with New York’s LaMama Theatre and a mix of US, Serbian and Kosovan actors. Last year, The Handke Project, a furious piece about the Nobel committee’s decision to bestow an award on Peter Handke, featured a mixed cast of Kosovan, Bosnian, Italian and Serbian actors. Negotiating Peace takes this international approach even further, with cast members drawn from the various coproducing theatres. All these shows are performed in English, which is at once a necessary comprise and may also make them more appealing as touring productions. This isn’t a model unique to Qendra Multimedia. Haris Pašović’s The Best European Show, which opened last week in Poland, has a similar approach with five co-producing partners and cast members from eight nations (you can read about that more here).

While this form of international collaboration has some pragmatic benefits, allowing for a pooling of resources, the way it brings together different cultures can also be creatively eye-opening, allowing for differing perspectives and lived experience of war in the rehearsal room which feed into the production.

Though Kosovo declared independence in 2008, it’s worth noting that for people in the country still, applying for visas to enter Europe’s Schengen zone, is a laborious and costly process. This adds another layer of complexity to touring any production. Visa-free travel has repeatedly been kicked down the road by the EU, and used as a bargaining chip.

Going underground – Teatri ODA, Pristina’s nightclub-turned-theatre

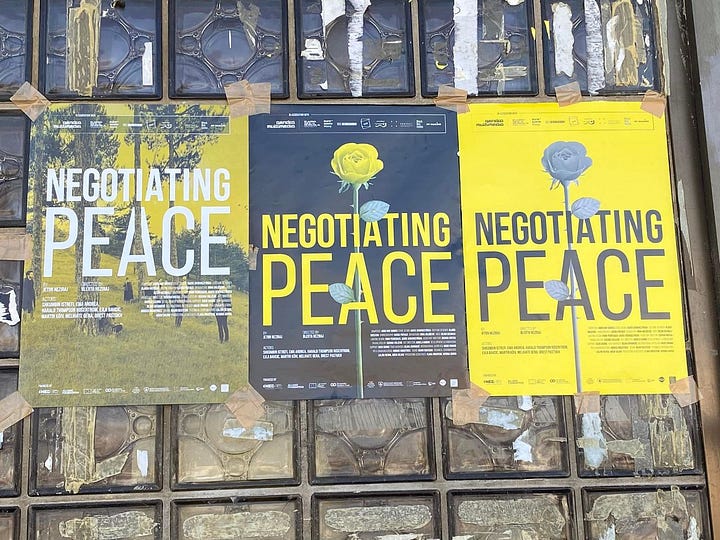

The premiere of Negotiating Peace took place in Teatri ODA, one of only three theatres in Prishtina, and one of the only independent theatres in the country. Located in the basement of the Palace of Youth and Sport, one of Prishtina's landmark Yugoslav era buildings which looks a bit like a concrete stegosaurus. It was once a nightclub, and in some ways still feels like one. You enter through metal doors in a carpark overlooked by the football stadium. Posters for the latest shows are pasted over old ones like gig flyers. A palimpsest of performances past. To reach the theatre you go down a flight of stairs into a room covered with wine-red striped wallpaper and photos of old productions on the wall, a bar at one end dispensing glasses of raki and bottles of gassy Peja lager. Up until recently the air used to have a furry quality, from all the cigarette smoke, but new, mostly adhered to rules have sent the smokers outside.

To pull off a technically sophisticated show with various live video feeds and projections in a space of this nature was impressive to say the least.

“Kafka of the Balkans”

Jeton Neziraj has been called the “Kafka of the Balkans”, which is handy shorthand, but only part of the story. He is skilled at pissing people off and recently caused a small storm in Serbian media because of comments made about a production at a theatre of the Serbian minority. In the past his plays have required a police presence for broaching sensitive domestic subjects, and he was briefly artistic director of the National Theatre of Kosovo but didn’t last too long in a role that requires a degree of political game-playing. His work has tackled corruption in healthcare (The Hypocrites, or The English Patient) and the building industry. (In Five Seasons: An Enemy of the People).

One of my favourite of his plays, Father and Father, is a relatively - and uncharacteristically - domestic drama that slowly reveals itself to be a story of haunting, of the emotional limbo of not knowing the fate of loved ones, a requiem to the 1600 still missing after the 1998/99 war. (You can read Verity Healey’s excellent review here).

There were times when Negotiating Peace felt in conflict with itself, the more dream-like, surreal elements jarring with the barbed satire of the negotiation scenes. The decision to make the ineffectual civil society representative an over-the-top parody of an environmental activist constantly banging on about recycled paper felt misjudged, a cheap joke, and I’m honestly still not completely sure what the panda was doing there, but Neziraj’s plays always have an urgency to them, this one more than most.

It was almost impossible not to watch such a play through the lens of current events that have in some ways overtaken it, both internationally – with the horrific events in Gaza - and domestically, with tensions in the north of the country still elevated after a shootout in a monastery last month left that three assailants and one Kosovan police officer dead and led to Serbian troops massing on the border for a mercifully brief but alarming period.

For all that the play satirises the process, the bottom line, as Blerta Neziraj said ahead of the premiere, is that Dayton stopped the war in Bosnia. Peace was achieved (the quality of that peace is another matter). The play scrutinises the inadequacies of the peace-making process and the fallible humans who make peace while always alert to the fact of what peace means.

This week in European theatre

Each week I do a small round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events. If you have recommendations for this section, please do let me know.

The Hours - Eline Arbo’s acclaimed production based on Michael Cunningham’s book about three women living at different points in the 20th century , including Virginia Woolf, returns to the ITA repertoire. The production in which Arbo creates a world in which the writer shares the space with his characters, will be performed at Internationaal Theater Amsterdam from 2nd - 12th November, with English surtitles on 2nd and 9th November.

The Beginning - Bert and Nasi are currently touring their new dance piece, a follow-up to The End, through Europe and the UK. The show has been made with the help of local communities in several locations across Europe and sees them working with 15 non professional participants, all aged 60 and over, wherever the show is performed. UK audiences can see The Beginning at South Street in Reading on 2nd November.

Fast Forward Festival – Dresden’s showcase of work by young directors features seven performances by emerging directors from across Europe, including Greece’s Mario Banushi, with Goodbye, Lindita, a richly visual, wordless piece about mourning rituals, and Findland’s Minna Lund with a mash-up of Fight Club and The Cherry Orchard called Message from Tyler - Memento Mori, Cherry Orchard (I know, right). The festival takes place at various venues in Dresden between 2nd-5th November. I will be writing about it in a future edition of Café Europa

Thanks for reading!

If you have any feedback, tips, thoughts or other comments you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com