Up she rises: Ophelia's Got Talent and the body art of Florentina Holzinger

On a feast of sword-swallowing, body piercing - and tap-dancing at the Volksbühne.

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

This week I’m in Berlin, where I managed to snag a ticket for one of the most talked-about shows in town, Florentina Holzinger’s Ophelia’s Got Talent at the Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. While I was there I reviewed, La Danse D’Amazon, the new show by Rimini Protokoll for The Stage. I also contributed a story about one of my weirder experiences as a critic to the most recent edition of Fergus Morgan’s ever-excellent The Crush Bar (welcome to everyone who found their way here as a result).

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, then please consider sharing it with friends or colleagues or anyone who might find it useful. Thank you to my new paid subscribers! Please consider becoming a paid supporter if your organisation is able, as it really makes a difference and will allow me to expand my coverage. As is the way these days, I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to keep me caffeinated. I want to keep as much of the content free as possible, so all donations are very welcome.

In Robert Altman's 1993 film Short Cuts, a tapestry made up of Raymond Carver short stories, Julianne Moore’s character has an argument with her husband while wearing just a T-shirt. Below the waist she's naked. Now Altman had no qualms about humiliating his female characters on screen (see MASH, Nashville etc for evidence of this), but in exposing Moore in this way she is not made smaller. As vulnerable as she is in this moment, she is also formidable.

In Ophelia’s Got Talent, Florentina Holzinger’s 2022 show for Berlin’s Volksbühne, everyone on stage is naked, either from the waist down or fully nude bar various harnesses and microphone packs. This is par for the course in one of her shows. Holzinger clearly loves bodies and the things they can do. Bodies of all shapes, ages and abilities. The Austrian choreographer and dancer’s career has gone stratospheric over recent years. She’s become a sensation both in the German-speaking theatre world and internationally, touring her work to Asia, Australia and the US. She’s been profiled in German Vogue. Next year she’s been invited to penetrate the opera world. When I step outside the Volksbühne to take some air, two people approach me to ask if I’m selling my ticket.

Her work is fleshy, messy, daring and – crucially - often very funny and playful. The Guardian called her 2019 piece TANZ, the only show of hers so far to make it to the UK, a “gross out, body horror ballet.” Her work is not just an ick-fest, it is full of classical reference, and an alertness to the history of dance and performance art. Her performers are frequently naked and there are bodily fluids of all kinds on display. There are feats of strength and risk. Bodies are set on fire. There is synchronised shitting and onstage tattooing. There are axle grinders and chainsaws. Previous shows have included acts of hair hanging and body suspension, in which a person is held aloft by a series of hooks pierced through their skin. Audience members have been known to faint (as discussed by Holzinger here). When her production of Appolon Musagète played New York's Skirball in early 2020, it made one US critic walk out in repulsion.

There is also tenderness and openness in her work, an exploration of fragility and strength, the whole human spectrum. In her 2015 piece, Kein Applaus für Scheisse, a male performer put his head between Holzinger’s legs and extracted a piece of red string. In TANZ, a woman in her 80s gives birth to a rat-baby. In her 2021 show, A Divine Comedy a woman on a hospital bed is pleasured with a strap-on. Many of her recent pieces also feature machinery, cars, motorcycles, over which the performers drape themselves, the juxtaposition of skin and metal.

Water, water, everywhere - Ophelia’s Got Talent

The opening set up of Ophelia's Got Talent is that of a cheesy X-Factor-style talent show. Three judges (naked, obviously) watch a series of routines by female performers (also naked, including a aerial pole act and a sword swallower) and deliver their verdicts. This goes on for some time until one of the stunts appears to go catastrophically wrong. There are a few heart-in-mouth moments where no one in the audience is quite sure whether or not this is real (the woman next to me raised her hands to her mouth in alarm). This kind of fake-out is a classic tactic, but when done well, as it is here, it enhances the sense of jeopardy and risk.

Once the talent show format has been dispensed with, Holzinger delivers a series of vignettes all connected to women and water, full of mythic and archetypal imagery. This leads to some gorgeous sequences. There are overhead shots of bodies scything through water (shot via cameras attached to fishing rods). There is tap dancing. There is a chaotic brawl. They sing ‘What Shall We Do with the Drunken Sailor?’. They perform a very entertaining version of ‘No Dames,’ Channing Tatum's number from the Coen Brothers’ Hail Caesar (itself an On the Town pastiche). One of the performers, Saioa Alvarez Ruiz, does a sexy dance with her mobility aid and a kitchen plunger.

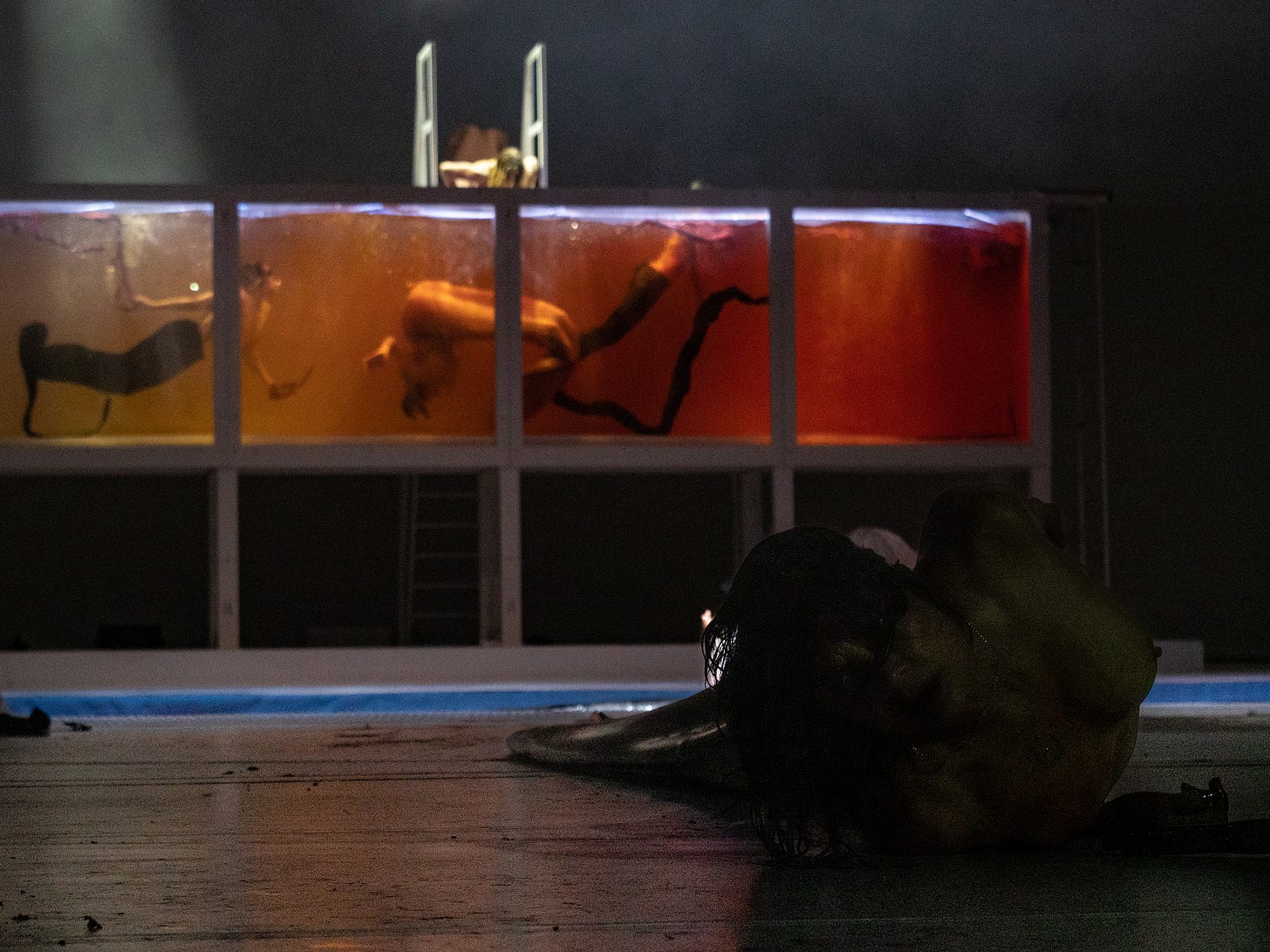

Water is the dominant motif. There are not one but three different water tanks on stage. An escapologist’s tank, another larger tank at the back of the stage and an actual swimming pool. Some of the performers spend large chunks of the show submerged. Others dive and splash in the tank at the back, which towards the end turns an ominous shade of red.

If they bother with clothes at all, the performers wear sailor’s tunics and inky mermaid’s tails. The show's host is dressed as a cartoon pirate, with a bottle of rum always close at hand. Even the camera operator is naked save for a pair of waders.

Later on in the piece, a storm is created using an industrial strength wind machine. The performers stagger around, the stage, their tunics billowing and hair streaming. Then a helicopter - a helicopter! - descends from above and the naked women clamber upon its metal chassis. They writhe and grind as the pirate humps the wind machine.

Ophelia does not put in an appearance until mid-way through as one performer recites Gertrude’s description of her death as Holzinger flops about inelegantly, refusing to drown gracefully, to lay Millais-like in the water.

I've had several conversations about her work that boil down to "ok, but what about the dramaturgy?" and I do understand that reaction. There is a throw everything at the wall approach to Ophelia's Got Talent. It can feel a bit like the dramaturgical equivalent of Gary Oldman in Leon bellowing "Bring me everyone!" (And if you had the resources of the Volksbühne at your disposal, why wouldn't you?).

Elsewhere I’ve heard her work described a welcome alternative to German dick-swinging directing culture, as a new form of feminine dramaturgy. I’m not wholly sold on this, but I do feel some of the criticism levelled at her work - that it is excessive, exploitative, too gross, too over-stuffed, too much - has a different flavour to that directed at her similarly confrontational male peers (at the same time I did find myself wishing the initial talent show segment was shorter and for a bit less pirate banter).

The element of Ophelia’s Got Talent that provoked the most post-show debate was the inclusion of a group of children. The kids, young girls of various ages, join the ensemble on stage halfway through and are there on and off for the rest of the performance, dancing and singing and swimming. Ophelia is billed as a show for over-18s, and there were concerns about questions of consent and their exposure to the material, but their presence also led to one of the most affecting sequence where these children hold up mirrors to the older performers. It was so simple a gesture it bordered on the trite, and yet it was moving, it was powerful.

Shock and awe, shame and pain

In between the set-pieces in Ophelia’s Got Talent, there are moments in which performers relate personal traumas. Holzinger discusses her childhood eating disorder. Another performer talks about a horrifying sexual assault during which she was raped and tied up. She tells this story while whole laying with her legs spread in front of another performer wearing a swan costume and wielding a speculum. As in much of work there's an ongoing interrogation of the role shame plays in our lives, exposing and exploring the experiences and the biological processes that we hide away, that we keep covered up. I found it interesting that some of these confessional sequences made me more uncomfortable than any of the physical business, though having said that I did find myself holding my breath every time someone got out a pair of rubber gloves and the antiseptic and/or lube, so it obviously was having an effect. For me, the show’s most striking moment followed Holzinger’s discussion of eating disorders, when two performers insert nasal gastric tubes, through which they run water. In this way they become a kind of human Renaissance fountain. It was at once visually witty, physically audacious and resonant.

Holzinger has talked about her delight in physical experimentation, in testing what the body is capable of doing, what it is capable of enduring. To this end she’s gathered a band of performers around her (including professional sword swallower Fibi Eyewalker and pole artist Sophie Duncan), a community of skilled women who use their bodies as instruments.

Is her work shocking? I guess it’s a question of framing. In previous interviews, she has talked about taking inspiration from Coney Island side shows, and about how you can draw a line between these and the body-art experiments of the 70s. Marina Abramovic was carving stars into her stomach decades ago. Most of the extreme acts draw from a long tradition of similar performance, from both sideshow tents and live art spaces. (Over my years of Edinburgh fringe going, I’ve seen multiple nails hammered up nostrils - hell, even Derren Brown does this - and people using their bodies in a variety of creative ways). Holzinger places these things on major German stages, within an institutional frame, and dials the volume up. There’s a sense that Holzinger is having a blast filling these spaces in this way. As she explains in this interview:

“I wanted people to be uncertain of where everything was going right from the start, to be on their toes from the first second – like, “Where the fuck did I end up?” – and for them to assume that there are no boundaries, which to be honest, there are none. If done with care and love, anything is possible.”

Towards the end of the show, following the aborted helicopter rescue, the mood gets darker, the waters murkier. There is a spectacular bottle drop sequence, in which a rain of plastic receptacles tumbles from above, contaminating the pool. The performers drag themselves around the shadowy stage, tails trailing behind them, though I have to say I found the lurch into climate catastrophe and environmental collapse felt a bit like an add-on, an afterthought.

Though Ophelia feels like it has about six potential endings, it finally concludes with a joyous dance to Ed Sheeran’s ‘Bad Habits’ which gets the audience on their feet. Despite the fact that someone got an actual tattoo on stage, it’s this sense of camaraderie, of female strength and community on stage that left the deepest impression, the sheer delight the cast take in undoing and unpacking the way the female form has been presented across art, across time.

This week in European theatre

Each week I do a small round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events. If you have recommendations for this section, please do let me know.

Prima Facie – Eline Arbo, who recently took over the role of artistic director of ITA, replacing Ivo van Hove, helms a new touring production of Suzie Miller’s one-woman play about the failings of the legal system in cases of sexual assault. The performance stars ITA ensemble member Marie Kraakman and opens in De Schuur, Haarlem on 30th November.

No Horizon - Japanese theatre artist, writer and director Toshiki Okada, whose previous show Doughnuts was selected for Theatertreffen Berlin 2022, returns to the Thalia Theater with a new piece exploring the nature of public spaces. It has its world premiere in Hamburg on 2nd December.

Notre vie dans l‘art – The new play by US playwright and director Richard Nelson – writer of The Apple Family play cycle and The Gabriels premieres his new work in Paris as part of Festival d'Automne. His first new work to be created in France, the play explores an evening spent by Stanislavski and his acting troupe from the Moscow Art Theatre in Chicago in 1923. Performed by the Théâtre du Soleil company, it opens on 6th December

Thanks for reading!

If you have any feedback, tips, thoughts or other comments you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com