Theatre of the thin place: Mario Banushi, fast rising star of the Greek stage

A look at the work of the young Greek director who's starting to make waves across European stages

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

This week we’re looking at a young Greek director Mario Banushi, who former Guardian critic Michael Billington called “an exciting new talent” and who I recently interviewed for Kosovo 2.0.

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, then please consider sharing it with friends or colleagues or, you know, anyone who might find it useful. Thank you to my new paid subscriber! Please consider becoming a paid supporter if your organisation is able, as it really makes a difference and will allow me to expand my coverage. As is the way these days, I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to keep me caffeinated. I want to keep as much of the content free as possible, so all donations are very welcome.

One by one the women start to judder, their bodies contorting, backs arching, limbs twitching, until, finally, one of them clambers onto the window frame and leaps out into the night.

This is one of many striking images in Mario Banushi’s Goodbye, Lindita, an at once very personal - it was inspired by the death of his stepmother - and richly sensory piece exploring Balkan rituals of mourning. It starts in near silence. A family move around a shadowed room, folding clothes and doing the vacuuming, life going on. But death is present and, in the first of many surprising moments, a chest of draws unfolds to reveal the body of a young woman. Her relatives gather around her. They keen and wail. They sprinkle handfuls of earth over her prone form. Then tenderly bathe and clothe her. They prepare her for her final journey.

There is no dialogue in Goodbye, Lindita, no defined characters, instead we have a series of beautifully constructed stage images and a focus on the sensual and atmospheric.

A visually rich triptych

Goodbye Lindita is the second part in a trilogy of pieces by Banushi, a young director who at the age of 25 is one of the fastest rising stars of the Greek theatre scene.

Banushi trained as an actor at the Athens conservatoire – he regularly appears in his own work – but soon after graduating in 2020, he started directing. Aged just 23 with no previous directing experience, he struggling to get funding and find a space for his first piece Ragada (which means Stretch Marks). A friend came to his rescue, and he ended up presenting it in the living room of a house in Athens.

In this setting it started to sell out. The success of Ragada led to Banushi receiving an invitation from the artistic director of National Theatre of Greece to create a new piece, but he was given a tiny window of time to come up with something. Still reeling after the recent deaths of his father and stepmother, with memories of their funerals fresh in his mind, Banushi decided to make a piece about grief. (You can hear Banushi talking about this process in a recent interview for BBC Arts Hour).

Goodbye, Lindita opened in March this year, and has proved so popular they’ve had to lay on extra performances. The concluding piece in the trilogy, Taverna Miresia: Mario, Bella, Anastasia - which was inspired by his father, or rather his absence - premiered at the Athens Epidaurus Festival this summer (the Guardian’s Arifa Akbar wrote about it here), where it sold out in only a few hours.

The child of Albanian immigrants, Banushi told me he was inspired by the stories his grandmother told him as a child, stories from her village, stories where the barriers between this world and the next are a bit thinner; he wanted to create that same sense of wonder and shock he felt as a boy in his audience. As a consequence, Goodbye, Lindita exists in a space of porosity, where the furniture and even the walls are untrustworthy, where hands emerge from picture frames, where things can reach through to us from the other side.

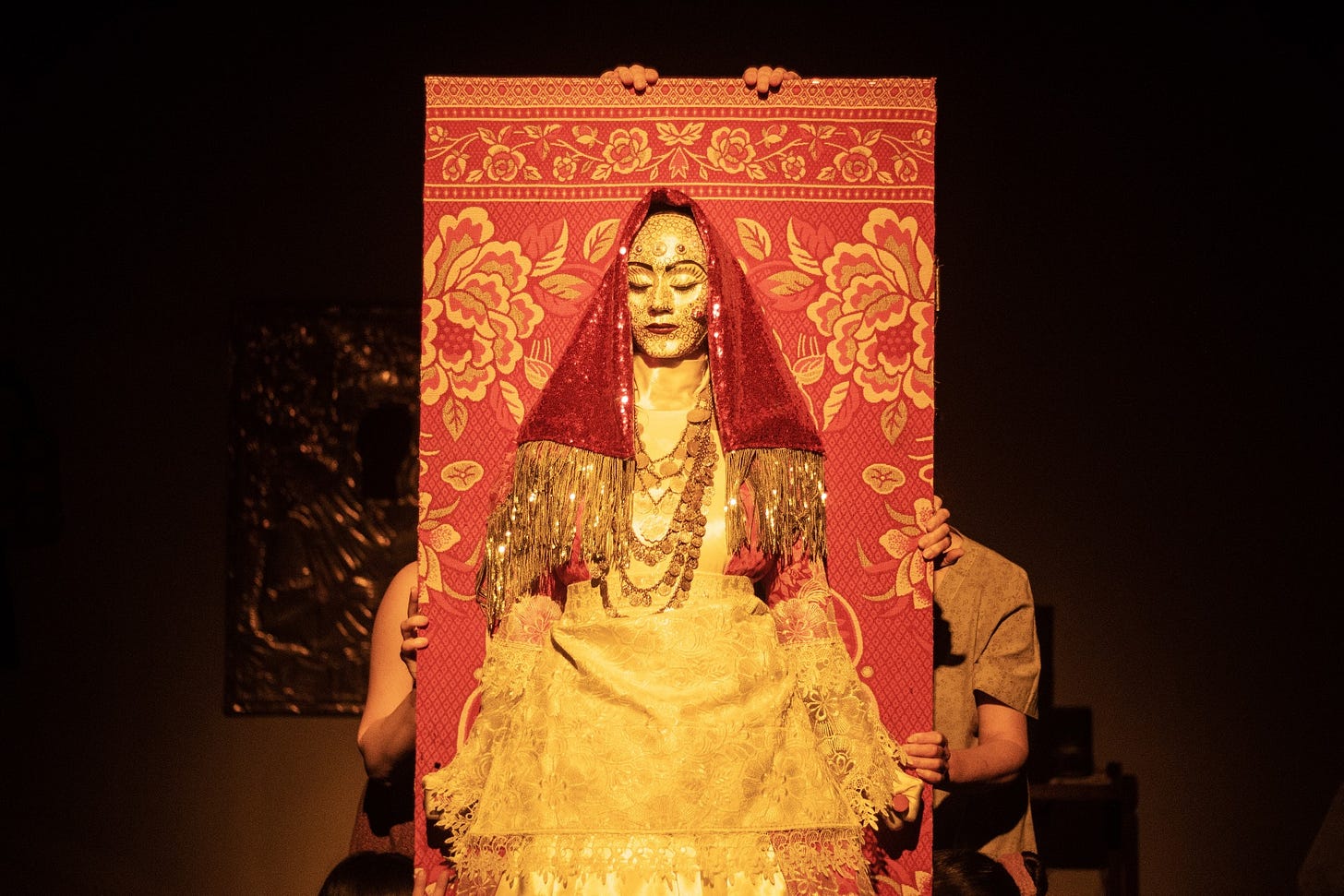

In the most striking moments in Goodbye, Lindita, the dead woman is clothed in white, red and gold traditional costume - bridal attire – before a death mask is placed over her face. This was inspired by the tradition in some rural communities when an unmarried woman dies of placing her in a wedding dress, as if her unmarried status was an affront to the natural order, something to be corrected in death.

Banushi offers no critique of the patriarchal custom. (One of the criticisms I heard of his work was its lack of social engagement). But what his work has in abundance is an already well-honed aesthetic sense, a richness of imagery. While he mentioned Tarkovsky, Sergej Parajanov and Pasolini as cinematic reference points, being differently orientated in my tastes I found myself thinking of Nic Roeg (what is Don’t Look Now if not the ultimate grief horror?), of folk horror classics like The Wicker Man and more recent films like Natalie Erica James’ matrilineal horror Relic, and as well as the work of the Belgian dance theatre troupe Peeping Tom. I think this is in part for the way Banushi utilises bodies. His work is very fleshy. Breasts are very present. There are naked bodies of all ages and shapes (mostly, though not always, female). In Goodbye, Lindita, we are presented with the paradox of the actor’s vibrancy vs her inertness, an uncanny living corpse. She is ritually bathed. A hand snakes between her legs. Later in the piece everyone disrobes, and their bodies are gripped by glitching, twitching spasms – physical manifestations of grief or of a spirit trapped between realms? (The soul tends to linger in the Balkans, it does not depart quietly).

The image of the Black Madonna is also central. Banushi took his inspiration from an icon ne encountered in a church on the island of Kythira. Inside the otherwise empty church he came across a lone woman kneeling before the icon in prayer. This image stayed with him. A replica of the icon hangs on the wall in Goodbye, Lindita. Later, we see her embodied by a performer. This is beautifully presented though also means that the only Black female performer in the piece is relegated to this otherworldly role. The final image is one of the most striking, an elderly woman crawling towards a welcoming and tender Madonna figure (Madonna/mother imagery ripples through his work), before being enfolded to her bosom.

So far I’ve written a lot about the visual aspects of the production, but sound plays a key role in his work. Taverna Miresia features haunting vocals by Greek singer Savina Yannatou, while Goodbye, Lindita features a disconcerting soundscape of fireworks and dogs barking, the mournful choral quality one encounters inside an Orthodox church coupled with birdsong and the chirrup of the television set. Towards the end the scent of intense permeates the theatre, sweet and heady.

In his debut piece, Ragada, you can see the formation of his style. Singers emerge from fridges. Flour is dusted over a woman’s naked body. Under the lights it lifts from her skin, like mist, like a fleeing spirit. Dough is moulded into the shape of breasts. A woman in a wedding dress cloaks herself like a ghost. We even get a bit of Bobby Darin’s ‘Blue Velvet.’ Here are the first appearances of motifs that will recur in his work: the washing of bodies, the veiling of faces, figures leaping through windows, the overlap between the domestic and the supernatural.

“An exciting new talent”

Goodbye, Lindita has not just proved popular at home in Athens. This autumn it embarked on a European tour, affording international audiences the chance to see it. At BITEF in October (you can read my review for The Stage here), the performance received the coveted Special Award Jovan Ćirilov. It was also recently in Dresden, where I saw it for the second time, as part of Fast Forward, which showcases Europe’s brightest emerging directorial talent (which I wrote about a couple of weeks ago). Next year it will play ITA as part of the Brandhaarden Festival, which in 2024 will partner with the Onassis Foundation and have a Greek focus.

He even has Michael Billington’s seal of approval. Here he is being exquisitely Billington about Goodbye, Lindita, which he saw as part of Greek theatre showcase earlier this year.

“At times I was reminded of the hyperrealism of the Bavarian dramatist, Franz Xaver Kroetz: Banushi makes great play of the way that families use telly-watching to nullify their emotions. At other moments Magritte came to mind: a door suddenly turns into a coffin, an arm miraculously appears from a wall as if the dead reach out to the living.”

“A new era for Greek theatre”

Banushi’s producer Nikos Mavrakis has worked with him since the beginning, with his company Too Far East Productions. ”As a director, Mario feels like home. He stands out for his warm heart and kindness,” he says. “Three years later we see our collective work coming to fruition and his hard work and talent being recognised. It is really rewarding.”

How, as a producer, does Mavrakis account for Banushi’s popularity? “Maybe the audience craves a piece of poetry, honesty and miresia - miresia is Albanian for kindness,” he says.

“It is very rare for a performance of the National Theatre or the Athens Festival to have such a significant international tour. It is even rarer for that to happen for an Albanian director based in Greece, says Mavrakis who is currently in the process of booking the tour of Taverna Miresia and seeking co-producers for Banushi’s next work.

“It marks the beginning of a new era for Greek and Albanian theatre. And we couldn't wish for a better example of a director to lead this effort. Mario is an example, not only for his kindness, but also because of his inclusive and collaborative artistic practice.”

While its wordlessness renders his work more accessible (and one might argue better suited to touring), the appeal of Banushi’s work lies in the way it intermixes religious imagery with the superstitious, the way it theatricalises the mystical, the way pain and memory are woven with folklore. Perhaps in the wake of a devastating pandemic which has been followed by a succession of brutal ongoing conflicts, with death filling our screens and dreams, this presentation of the rituals of grief offers audience’s something primal, but for me the appeal lies in the atmospheric world-building, the intoxicating sense of the strange, the dash of old magic.

This week in European theatre

Each week I do a small round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events. If you have recommendations for this section, please do let me know.

MIRfestival – We’re staying in Greece for an international contemporary art festival with a focus on experimental work and visual new media. Dance, live art, lecture theatre and work not easily put into boxes is on the menu from a mixture of Greek and international artists. The festival runs from 23rd-30th November.

DunaPart - Organized by Trafó House of Contemporary Arts, the biannual DunaPart festival is designed to showcase the work of the Hungarian independent performing arts scene, which has been seriously squeezed under Orban, to an international audience and create new connections. Featuring theatre, dance, puppetry and cross-form work, the packed four-day programme takes place in Budapest between 23rd- 26th November.

la danse d’amazon - Part of the mammoth ULYSSES European Odyssey project, this new piece from Rimini Protokoll sees them collaborate with the anti-consumerist group Peng! Collective and the Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz on a circus spectacle which takes aim at online retail behemoth Amazon and coincides with a campaign and a day of action on ‘Black Friday.’ It premieres on 23rd November at the Cabuwazi circus tent in Berlin.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, thoughts or other comments you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com