The crying game: Robert Icke's Manhunt

On a new play about Raoul Moat and the responsibility of telling true-life stories on stage.

This is the April bonus edition for my growing number of paid subscribers. I’m really grateful for your support. It makes a real difference. If you would like to become a paid supporter, you can do so for £5 a month or £50 a year. If that’s not an option and you’re still keen to read this, drop me a line and I’ll share it with you. There will also be the regular free-to-read newsletter in your inbox on Wednesday.

For a week in July 2010, Raoul Moat’s name was everywhere. Recently released from prison where he was serving time for assaulting a child, the 37-year-old shot his ex-girlfriend Samantha Stobbart and her new partner Christopher Brown (wounding her and killing him). Then he shot and blinded police officer David Rathband, before hiding out in the hills around Rothbury in Northumberland. The story of the subsequent manhunt – the largest in UK history - was all over the newspapers at the time, all over social media. The coverage was feverish and lurid - and a little weird. Celebrity woodsman Ray Mears got involved at one point. You couldn’t escape it. The manhunt eventually concluded when Moat killed himself during a standoff with armed police. And that was that.

Except, no, obviously, it wasn’t because Moat’s story has been the subject of numerous books, countless podcast episodes and even an ITV series, The Hunt for Raoul Moat. His story keeps getting retold and retold. Now it’s the subject of a new play by Robert Icke, a director with a reputation for creating stylish and lucid versions of classical texts, the Oresteia, The Wild Duck, The Doctor and most recently a tense, contemporary Oedipus which netted Lesley Manville an Olivier Award (a production which originated at Internationaal Theater Amsterdam).

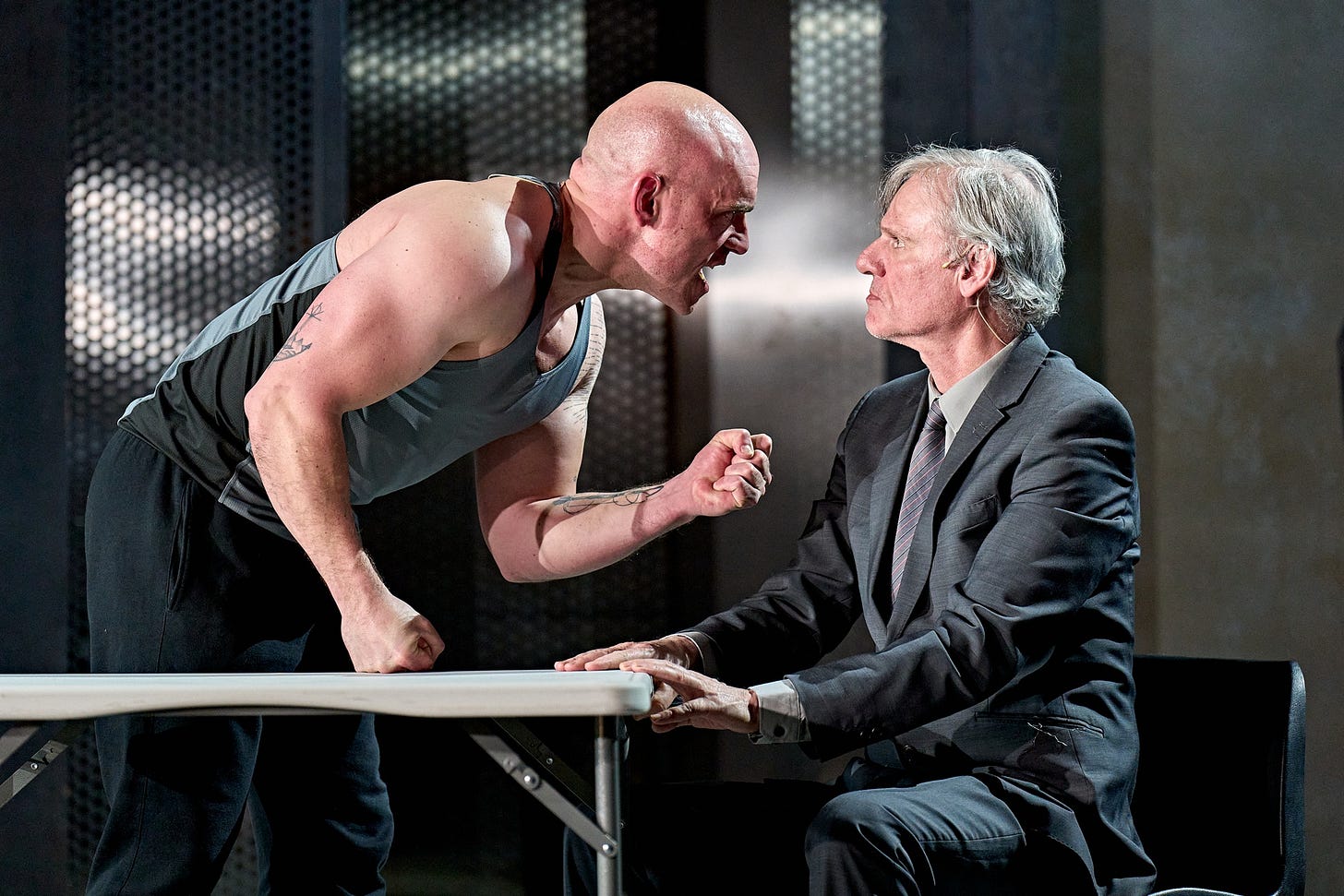

Moat is played by Samuel Edward-Cook, who dominates the stage, pumped up and physically imposing, his scalp glistening with sweat. The first thing we see is that head, shot from above as he nervously paces his cell. Icke essentially invites us into Moat’s mind. We hear his voice. His words. Icke frames the play as a trial, a kind of posthumous cross examination in which he’s regularly questioned by a barrister. Sometimes a character will say something, and Moat will point out that they never actually said this in real life. Sometimes the barrister will put it to him that he’s exaggerated something or made something up - he fabricates an absent French father, for example, having never known who his real father was. He’s presented as someone with a massive capacity for self-pity, for painting himself as the victim and for placing blame on others, on social services, on the police, on the system. That’s not to say there weren’t failings in these areas, but Moat clearly feels he’s being harassed, picked on, hard done by - that everyone’s to blame but him.

We know he is not to be trusted as a narrator but what’s unclear is what Icke wants us to do with that. I’m a fan of ambiguity but there’s a muddiness of intention here. The form Icke has chosen, writing from Moat’s point of view, giving us access to his anxieties about his body – he was obsessed with bulking up, with being as big as possible, viewing his muscles as armour - about his relationship with Sam, about his sense that the whole world was against him, creates a sense of connection. Obviously, Icke wants this connection to be complicated and uncomfortable for the audience, but the play still fails to answer the question of why it’s telling Moat’s story again, now.

Because it is Moat’s story. It’s definitely not the story of the woman he shot. The play talks about the age difference between them but glosses over the fact she was 16 when they first started seeing each other. It glosses over his history of domestic violence and being abusive towards women. That’s not to say Icke doesn’t show Moat being violent towards Samantha. He does. He has Edward-Cook grab Sally Messham, who plays Samantha (and also played her in the ITV drama), by the hair and hurl her across the floor, when he’s not flinging chairs around Hildegard Bechtler’s perforated metal set every time he loses his temper, which is often. But these moments, as with the rest of the play, are very much seen through his lens.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Café Europa to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.