Pump up the volume: Why actors in Serbia have been striking

On the ongoing student protests in Serbia and how cultural workers are showing solidarity.

I’m back in Belgrade this week where the current wave of student protests has continued apace. There are new developments every day, which is one of the reasons why I wanted to revisit this story. But it’s also a story of hope and resistance and given everything that’s going on in the world at the moment, a story that will have resonance beyond Serbia.

If you missed my earlier piece on the protests, and how the theatre community has been supporting them, you can read it here.

If you want to support my writing while keeping this site largely paywall-free (though there will be occasional paid subscriber bonus posts, like this recent round up of theatre I saw in London), you can do so for just £5 a month or £50 a year. Or just share this newsletter with someone you think might find it interesting. That helps too.

The theatres in Serbia went dark last week. From 10th-17th, all the country's major institutional spaces shut their doors as part of a country-wide actors’ strike. The decision to strike was taken as an act of solidarity with Serbian students who have, for over three months now, been engaged in a wave of anti-corruption protests that some have said are the largest the country has seen since 1968.

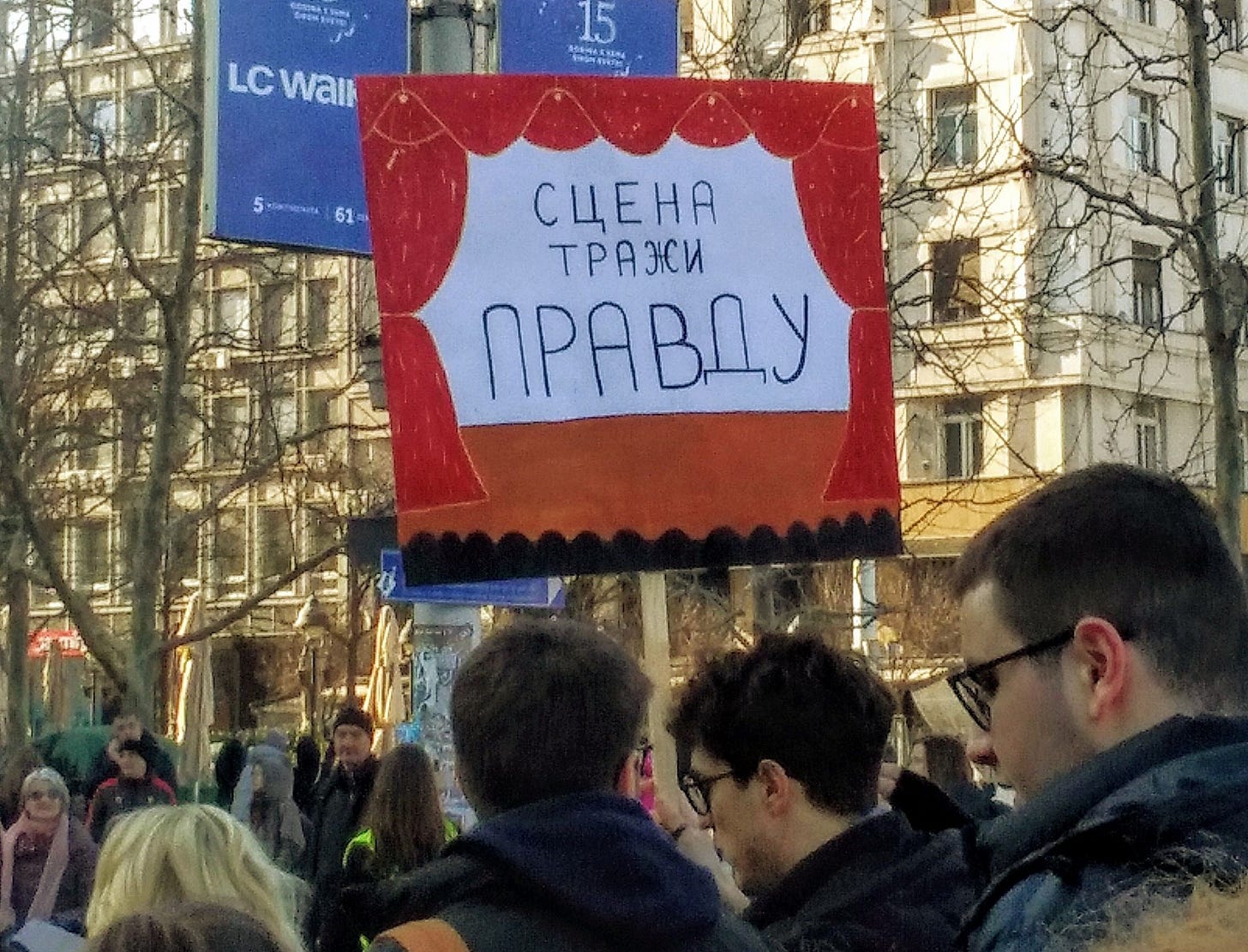

On 11th February, as students marched through the streets of Belgrade, ensembles from various theatres assembled in from their respective venues and greeted the students with placards, cheering and, in some cases, songs. Various performative acts were staged in front of some of the country’s theatres as well as at the rectorates of Belgrade and Novi Sad Universities and the strike culminated in a protest in Novi Sad, Serbia’s second city, on 17th February.

The strike was unprecedented in Serbia. Almost all theatres in Belgrade participated in the strike - Zvezdara Theatre initially mooted the idea of staying open and giving students free tickets but they eventually joined in - as well as all theatres in Novi Sad and theatres in several smaller towns including Sombor and Zrenjanin.

Serbian actors had already been demonstrating their support for the students, often by sporting red gloves – bloody hands have come to be a symbol of the anti-corruption protests – during curtain calls. “The audiences’ responses were remarkable,” says actor Dragana Varagić. “Now we are silent, so you can better hear the voices seeking justice. We, who work in theatre, know well how powerful silence can be.”

The strike was not just a show of solidarity with the students, however, but also an answer to the students’ request that people start addressing the systemic problems in their own fields and institutions. The striking cultural workers made a series of demands including an increase to the budget for culture and better salaries and working conditions, as well for state media to stop prosecuting theatre workers who support student protests. One cultural worker at Šabac Theatre recently lost her job as a direct result of attending the protests and actors are regularly singled out on state media for their support of these, and previous, protests.

In addition to the strike action, the theatre community has been supporting the students in other ways. There have been several performances for students at their faculty buildings. Varagić has participated in some of these, performing the hit show Our Son for students, against a backdrop of banners and protest posters. Post-show discussions after these performances are often “very emotional on both sides,” she says, “but also provide lively discussions on various topics related to the shows and political crisis we are in.”

The students have also continued to produce their own work, including a student-directed production of Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, which was performed in Novi Sad recently, for an audience of their fellow students. (Here’s an article in English about that performance by Serbian critic Divna Stojanov)).

These protests were sparked by the tragic deaths of 15 people after a canopy collapsed at Novi Sad railway station on 1st November. For many people this was a tipping point, the deaths a direct consequence of a corrupt and broken system in which loyalty to the ruling Serbian Progressive party (SNS), which has been in power since 2012, is valued more than competence.

On 22nd November, students of the Faculty of Dramatic Arts were attacked while holding a silent vigil for the dead. They blockaded their faculty in response, demanding that those responsible both for the train station collapse and the attacks on them, be held to account. Other faculties followed suit. Since then, the protests have continued to grow and evolve. Rarely a day passes without some kind of protest or action. The students have organised mass gatherings. They have blocked bridges. They handed 1000 identical letters to the Serbian Supreme Public Prosecutor asking that she do her job properly. On 27th January, they staged a 24 hour-occupation of a major highway intersection in Belgrade, camping out overnight. Throughout all this, they have remained steadfast and clear in their demands. They are fighting for their right to live in a country where the rule of law is observed and where the institutions function as they should.

“On one hand, this feels like a fairly simple request,” explains theatre critic – and student - Borisav Matić. “On the other hand, it’s a utopian demand. If these institutions truly started functioning again, the whole society would transform, including the situation on the cultural scene. Theatre artists are aware of that – by joining the students’ battle, they are also fighting for themselves,”

It’s not only theatre workers who have been expressing solidarity with the students. Farmers - and their tractors - have been present at several protests. Lawyers and education workers have organised strike actions, and on 24th January, a general strike was held which saw cultural spaces and many shops and businesses shut their doors. Nor are the protests limited to the big cities. The spirit of resistance has been spreading around the country, to the smaller towns and even to the villages.

The protests haven’t been free of incident. On several occasions cars have driven at the protestors, on one occasion seriously injuring a young woman, while in Novi Sad, masked thugs beat up another female protester, breaking her jaw. This hasn’t deterred the students, if anything it’s galvanised them further.

In recent weeks the students have started marching, cycling and, in some instances, running across the country. This is an inspired idea in many ways, since it allows them to come into contact with people from smaller places. At the end of January, the students embarked on a two day walk from Belgrade to Novi Sad, roughly 70 kilometres with an overnight stop. This walk took them through small towns and villages where you might expect support for the ruling party to be strong, but, more often than not, they’ve been met with cheers and tears and open arms (and food, a lot of food – wherever they’ve gone they’ve been greeted by roasted meat and pots of gulas and beans, and in some cases pogača, a kind of traditional bread, served with a pinch a salt – a symbolic gesture of welcome).

While it took a long time for the world’s media to notice what was going on in Serbia , the New York Times published this piece and there has been several articles in the Guardian, including this one. There have also been an increasing number of diaspora protests everywhere from London to Las Vegas. Marina Abramović published a statement of support of the students; Madonna posted a story in support of Serbian students on Instagram (which is not a sentence I expected to find myself writing). Novak Djokovic has been spotted wearing a ‘Students Are Champions’ t-shirt.

This past weekend, students concluded a gruelling four-day hike to Kragujevac, a city in central Serbia to coincide with Serbian Statehood Day. The 15th February is a significant day in Serbia, marking the publication of the first constitution in Serbia in Kragujevac in 1835. Some students carried copies of the Serbian constitution in their hands as they marched. Along the way, they received a similarly warm reception wherever they went. They were hugged and fed and offered medical care for their battered and bleeding feet. When the authorities attempted to thwart their plans to sleep in public buildings, locals found them places to sleep. In one case a family let them bed down for the night in the plastic greenhouses on their farm. When they finally arrived in Kragujevac, they were met with more cheers and fireworks, a real heroes’ welcome. The day afterwards a convoy of taxi drivers volunteered to take them home free of charge.

While the tragedy in Novi Sad triggered this wave of protests, they speak to a wider discontent with the current regime. On the face of things Serbia is economically healthy. The country has a strong tech sector, unemployment is falling, wages are rising, but at the same time rent has skyrocketed in recent years and food prices in supermarkets are on a par with, or sometimes higher, than many western countries meaning that your money doesn’t go as far. Obviously this true of many places, but that doesn’t capture the reality of what it’s like to live in this country as a young person, fearful for your future. Living under such a system takes a toll. As Varagić explains, Serbia is a country where people with “no expertise run some of the biggest public companies, where you can buy a university diploma but cannot get a job in a public sector with your real diploma unless you are a member of a ruling party, where judges and prosecutors are silent and invisible.”

The media plays a large role in this. It’s hard to overstate how much the President Aleksandar Vučić dominates the media. Barely a day passes without him appearing on television talking about how well Serbia is doing, sometimes with the aid of a chalkboard, or being ‘interviewed’ on friendly channels like Pink or Happy. The students have, however, succeeded in decentring him from the national narrative. They are simply not interested in what he has to say, and he does not have a game-plan for this.

Vučić has alternated between attempts to appease the students and discredit them, accusing them of being manipulated by “foreign influences” and talking of ominous forces out to destroy Serbia. On the day of the gathering in Kragujevac, the ruling party staged a counter-rally in the northern city of Sremska Mitrovica, in which people were bussed in from neighbouring Republika Srpska, the Serbian majority entity in Bosnia. To an audience of party loyalists and those who had been pressured to attend, he declared himself victorious over the “colour revolution.” In Kragujevac meanwhile, the students held their silent vigil and sang songs together. Fifteen empty chairs were assembled for each of the people who died in Novi Sad. The contrast was marked. The students also scrupulously cleaned up after themselves, as they do wherever they go.

What sets these protests apart from other recent protests in the country is how the students have organised themselves. They have no leader, no figurehead. Everything they do is decided by plenum. They also have no political affiliation. They are pooling their skills, drawing on their different fields of study, be it economics, engineering, politics, law or the dramatic arts, and they are incredibly social media savvy. In a landscape of “media darkness they use social media effectively,” says Varagić. In keeping with the tradition of past Serbian protests, the students also understand the value of humour, turning up at one protest with an enormous sandwich stuffed with money (a Serbian in-joke, since Vučić has been known to entice people to attend rallies with the promise of free sandwiches).

This is a fast-moving situation. Every day some new action is announced. Just last night a blockade was announced at the Belgrade Cultural Centre. Even as one protest is taking place another is being planned. What’s lacking is a clear end-goal. There’s no real way their demands can be met without widespread systemic change and it’s hard to imagine how that can happen under the current regime. The question of how long they can keep this up feels ever more pressing.

I asked Matić how he has been feeling through all of this. “In November, after the canopy collapse and before the sufficient reaction from the public, I felt depressed,” he said. “In December, I felt incredibly excited because such a student movement was forming that Europe hadn’t seen anything like it since 1968. In January, I felt anxious because violent attacks by pro-government hooligans were at a high. Now, in February, I feel as if we’re in a new normal, that is, we are in a long-haul fight. But what connects these periods since December is the feeling of hope that social change is possible, a feeling that has shattered the resentment and apathy that have kept the status quo in place for so many years, even decades, in Serbia.”

“We thought this generation was just waiting for a chance to leave the country,” says Varagić, “as so many highly educated young people have left before seeking better lives elsewhere, but we were wrong. The students in the protests want to stay. And they have a lot to say.”

Thanks to the students, she says, “words like hope, empathy, nonviolence, and knowledge are back in use.” They have brought “decent, thoughtful and proactive language into the public discourse.” In their actions and the way in which they organise themselves, she says, “the students bring hope that we can make the system work for the public good if we work together.”

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days

Mother Courage – Belgian director Lisaboa Houbrechts, who clearly has an affinity for theatre’s most complex female characters having previously directed productions of Medea and Yerma, takes on Brecht’s anti-war play, staging the original in its entirety with a diverse multilingual cast. It opens at KVS in Brussels on 20th February.

Otherland - Chris Bush – the UK playwright behind, amongst many, many other things, the musical Standing At The Sky’s Edge and the Katie Mitchell-directed (Not) the End of the World at the Schaubühne - has a new play about breaking-up and other transitions at London’s Almeida Theatre. Directed by Ann Yee and featuring an all-female cast, it opens on 20th February. Here’s a really great interview with Bush about the play for Exeunt.

Romeo and Juliet – German writer and director Bonn Park’s production of Shakespeare’s tragedy of young people falling in love in a climate of hate is billed as an ‘Italo disco opera,’ which certainly makes it sound more intriguing than most productions of the oft-staged play. Featuring music by composer Ben Roessler, it has its world premiere at Zurich Schauspielhaus on 22nd February.

Thank you for reading!