London round-up: Opening Night, An Enemy of the People, Nachtland, The Hills of California, Shifters and Foam

I went to London, saw some shows and had some thoughts.

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

This week I was in London, where, as you will see, I squeezed quite a lot of theatre into a relatively short visit.

If you find this newsletter enjoyable, interesting or otherwise useful, please do consider sharing, subscribing or, if you are able, becoming a paid supporter. I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to support my writing that way.

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre

Ivo van Hove. Rufus Wainwright. Sheridan Smith. Until a few months ago I suspect these are names you would not expect to hear in the same sentence, much less encounter in the same stage production. And yet here we have Ivo’s new production of John Cassavetes’ 1977 film Opening Night, a portrait of an actress in emotional turmoil.

Sheridan Smith plays Myrtle Gordon who, in the midst of previews for a new play The Second Woman, is starting to unravel. She’s struggling to connect with the text, in part because she worries that if she convinces as a woman in the grip of menopause, it’ll restrict the future parts she’ll get to play. Once she’s an older woman in people’s eyes, that will be that. She also worries that she is losing touch with her own emotions, which were easier to access as a younger woman. Her penchant for bourbon isn’t helping her already fragile mental state, and her distress is compounded after she witnesses the death of a 17-year-old fan in a car accident outside the theatre.

A documentary crew is filming the rehearsal process which is basically an excuse for the constant presence of cameras on stage. Images of the performers’ faces in tight close-up are projected on the back wall, capturing every pore in HD along with significant amounts of spittle during the musical numbers. As well as Blair Witch up-nostril shots, we also get overhead footage of the stage, which sometimes slips out of sync with the action. This intensifies as Myrtle starts to hallucinate the dead girl, embodied by Shira Haas, star of Netflix’s Unorthodox, an impish figure in a white lace dress. (Eventually Myrtle has to literally wrestle the ghost-girl out of her head).

Myrtle can’t get past the place in the play where the actor playing her ex Maurice is required to slap her on stage. Every time he does it, she collapses, and she is more generally resistant to the idea of being humiliated on stage (which, given some of Van Hove’s previous work, feels a little like meta-commentary). The show also contains the by now obligatory outdoor sequence as a wildly intoxicated Myrtle crawls into the theatre from the street (still looking impressively cool in leopard print jacket and shades), so plastered she can barely stand and then somehow her instincts kick in and she delivers the performance she was unable to access before.

Smith eats this up. Always a performer adept at blending pathos and comedy, she brings nuance and warmth to Myrtle. While Gena Rowlands performance in Cassavetes’ film felt more coolly controlled, Smith has a way of letting the audience in, like she’s missing an epidermal layer. She’s just so open. She brings humour too - when she complains she doesn’t get to be funny on stage, it feels realer for her than it does for Rowlands - and, ultimately, a sense of quiet triumph to the role.

All the men, including Hadley Fraser as director Manny, are a bit background in comparison. Nicola Hughes gives a roof-lifting vocal performance as the playwright Sarah, a woman on the other side of menopause who’s concerned about her creative vision not being respected, but the show doesn’t give her much room. Amy Lennox is even more underused as a character who is so thin, it basically just boils down to ‘wife.’

The songs are very Rufus Wainwright-y. The whole thing feels more concept album than full-on musical, the music more about sensory texture and heightened artifice, at times jazzy, at times operatic, though Wainwright’s insistence on repeatedly rhyming ‘magic’ with ‘tragic’ in the opening number did make me laugh.

This is actually Van Hove’s second crack at staging Opening Night, following his 2006 production with the Dutch ensemble at what was then Toneelgroep Amsterdam (here’s Variety’s review of the earlier production). He also covered similar thematic ground with All About Eve (sucking much of the joy out of the material in the process). Given that Jamie Lloyd’s Sunset Boulevard has only just vacated the West End, it does sometimes feel like playing an actor worrying about the work drying up is one of the leading parts still open to women past a certain point (also Smith is only 42, which maybe kind of the point of the show, but also ffs).

The show has split critics in a fascinating way. There have been some spectacularly negative reviews and a few champions – here and here – of its weirdness. And, to be fair, it is a weird show. It’s woozy, wonky, not wholly coherent, the different elements rarely gelling, but Smith, with her vivid mix of rawness and grace does wonders, making for a more enjoyable experience than some of Van Hove’s recent offerings.

An Enemy of the People, Duke of York’s Theatre

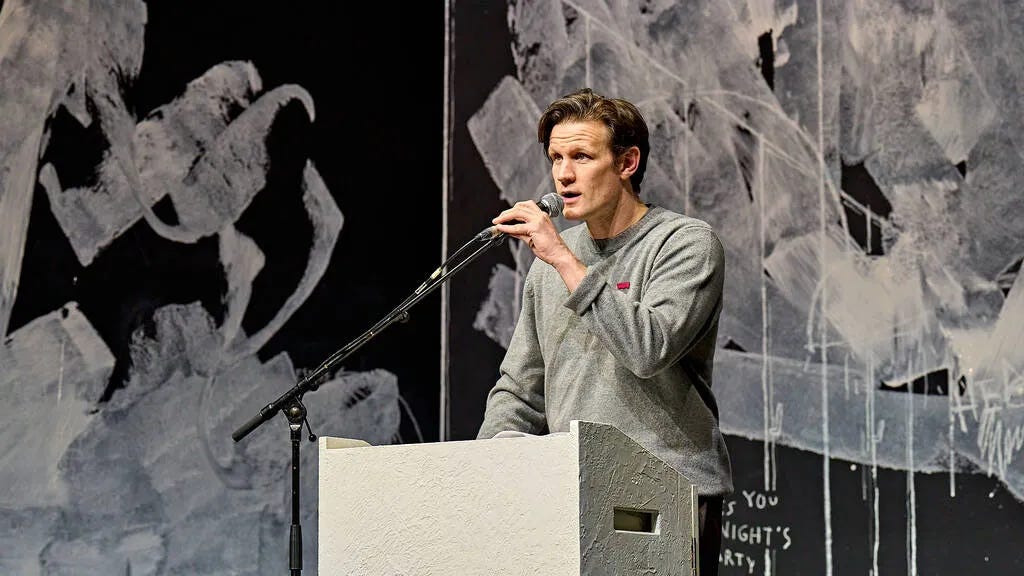

Thomas Ostermeier’s production of An Enemy of the People has s been around for a long time. Having premiered at the Avignon Festival back in 2012, it’s become one of the best known shows in the Schaubühne repertoire and has toured globally. London audiences had the opportunity to see it at the Barbican in 2014. As the production hits adolescence, a new English staging has opened in the West End with a UK cast including former Doctor Who Matt Smith. He plays another doctor, Thomas Stockmann who realises that the waters of his town’s spa/cash-cow are contaminated with industrial waste and tries to publish an exposé in the press only to find the town’s other residents, including his uptight politician brother, are reluctant to take action and jeopardise the town’s main source of income.

Ostermeier and Florian Borchmeyer’s adaptation has been reworked by Duncan Macmillan, with references to Covid and the current political climate, but otherwise the production is a facsimile of the original, with the cast jamming together in the opening scenes.

Famously the production hinges on a townhall debate in which Stockmann, having had his naïve idealism shattered, delivers a lectern-thumping speech about the state we’re in. He rails against moral bankruptcy and the “liberal majority.” This country doesn’t have a cost-of-living crisis, he rages, it has an inequality crisis, his rhetoric becoming increasingly more incendiary as he goes on.

Then the audience is invited to weigh in. People are tentative at first but once one person has spoken, others raise their hands. There are some impassioned contributions, (including one from my companion, about the erosion of the right to protest). But when it gets particularly interesting, when one audience member flags up the eye-watering cost of her stalls ticket, the cast kind of make a joke of it, and steer the debate elsewhere, instead of letting the discussion run.

Tonally the show feels somewhat broader than I remember the German production being (which, to be fair, I only saw online), a little more on-the-nose, the performances bigger. Paul Hilton is a slippery, liquorice-limbed politico, slithering around the stage in his blue suit, while Zachary Hart is jester-like in the way he primes the audience for the interaction ahead. Smith and Jessica Findlay Brown, as his wife Katharina, are more restrained. Smith has the air of a righteous teenager who naively assumes he’ll be valorised for bringing the situation to light. He impressively funnels this energy into his oratory scene. But, perhaps because of the West End framing, the whole thing feels a little contained. This is true even if of the climatic paintball scene. Its chaos feels excessively organised. The one exception is the moment in which Shubham Saraf gets a bucket of paint straight in the face.

Incidentally, the show’s producers Wessex Grove (also the team behind Opening Night) previously brought Ivo van Hove’s production of A Little Life to London, once again with a British cast replacing the original Internationaal Theater Amsterdam ensemble. It’s an interesting model. On the one hand it feels a bit like photocopy theatre, art as franchise, but I can also appreciate that it is a canny and increasingly common - Eline Arbo recently remounted her production of The Hours with a Danish cast at the Theatre Royal in Demark, for example - way of extending the life of a piece of theatre, and allowing it to reach more people.

Nachtland, Young Vic

The original production of Marius von Mayenburg’s play Nachtland also originated at the Schaubühne, premiering there in 2022. Patrick Marber directs the UK production of a play engineered to push buttons. Siblings Nicola (Dorothea Myer-Bennett, a late-in-the-day replacement for Romola Garai) and Philipp (John Heffernan) are arguing over the possessions of their recently deceased father when Nicola’s husband Fabian (Gunnar Cauthry) finds a painting in the attic. The painting is kitsch as hell, a twee little church scene, and they’re debating whether to throw it out when they spot the artist’s signature - A Hitler

Now Nicola and Philip find themselves in a position where, if they can prove the painting’s provenance, that is an authentic Hitler artwork, they can potentially make a boatload of money, something which goes down as well as you can expect with Philipp’s Jewish wife Judith (Jenna Augen). The idea that they would profit of such a thing repulses her, but her protestations are dismissed by Philipp and met with increasingly blatant antisemitism from Nicola.

It is a play designed to make its audience uncomfortable, to the point it almost has a visible tick-list of culturally sensitive topics designed to make a contemporary German audience squirm. The characters are not so much characters as ciphers, mouthpieces for the arguments the play wants to make. Subtle it is not.

In the Schaubühne production, which von Mayenburg himself directed, the stage was covered in ugly brown shag pile carpet - something under which inconvenient things can be swept. Marber’s production takes place on a thrust stage dominated by designer Anna Fleischle’s set, the side of a ruined house that looks as if a bomb has carved a path through it. There’s a flatness, however, to Marber’s production, as if he couldn’t quite figure out where to pitch it in terms of tone. This is reflected in the performances. You get a sense of actors groping around for some hook on which to hang their characters. Angus Wright, as an art buyer who is fascinated with Hitler and who eventually offers to up the price if Judith will have dinner with him, seems most at ease with the material, giving a flamboyant, seductive performance. The others seem less comfortable. Marber’s production contains a scene where Wright gyrates around the stage in slashed leather shorts, but this stylistic detour and willingness to send-up cultural stereotypes is momentary and the production feels theatrically underpowered, never quite locating the right balance of absurdism and irony, which in turn makes the arguments about tainted art and the weight of the past feel heavy-handed.

The Hills of California, Harold Pinter Theatre

Following The Ferryman, Jez Butterworth has teamed up again with Sam Mendes, this time bypassing the Royal Court to open straight in the West End, with The Hills of California, a time-hopping family saga of broken dreams set in Blackpool hotel during the heatwave of 1976.

The Webb sisters have returned to the family home to be with their mother in her last days. She is expiring from stomach cancer in an upstairs room. As children she groomed them for stardom, drilling them to become Blackpool’s equivalent of the Andrews Sisters. Quiet Jill (Helena Wilson) has put her own life on hold to look after her mother, Ruby (Ophelia Lovibond has resigned herself to the tedium of married life, though she is prone to panic attacks; Gloria (Leanne Best) is brittleness personified, spiky and resentful. Only eldest Joan escaped to live a glamorous life overseas.

The play shifts back and forwards in time between the 1970s and the 1950s of their youth, Rob Howell’s multi-level set rotating as we are transported back to the past. Laura Donnelly plays Veronica, the Webb family matriarch, who having raised four girls alone, is determined to steer them towards success. The first half of the play spends a lot of time establishing the sibling dynamics in both the past and the present, the rivalries and resentments as well as the affection, the shared past. With the arrival of an American producer at the boarding house, the lengths to which Veronica will go become apparent. Mendes does a superb job of building tension in the lead up to this moment.

The second half of the play, in which prodigal Joan finally returns, we learn about the fallout of Veronica’s actions, and the family mythology starts to collapse in on itself, is less dramatically satisfying. In part this is because Butterworth and Donnelly have made Veronica such a big presence in the play that it suffers when she is absent (even if Donnelly herself is not). Veronica is not a caricature of a monstrous stage mother, she is more complicated than that, as proud as she is rigorous, a woman familiar with disappointment and regret, a combination that leads her to make an appalling decision.

Whereas The Ferryman used its length to build towards a devastating conclusion, here the play feels a bit padded out in places (not everything needs to be three hours long, Jez) and the plot strands introduced in the second half only clutter things up. There’s some intriguing ambiguity surrounding Joan’s story, where she’s been and what she’s been doing in the intervening years, but the play never wholly leans into this. The play is never less than engaging, and Butterworth knows how to write a layered character (and Donnelly knows how to play one), but all of this can’t stop it from feeling a bit over-stretched.

Shifters, Bush Theatre

Benedict Lombe won the 2022 Susan Smith Blackburn Prize for her debut play Lava. Her new play Shifters takes the form of two-hander about Dre (Tosin Cole) and Des, short for Destiny (Heather Agyepong), two sometime lovers who first met when they are at school. The two are from different backgrounds. He is a British Nigerian being raised by his beloved gran; she is British Congolese being raised by her neurologist father after the loss of her mum. Despite the economic and cultural differences, there is a connection between them. Lombe’s play shifts backwards and forwards in time, granting us glimpses of their lives over the years, resisting the urge to make everything explicit, leaving us to fill in the gaps.

Des becomes a successful artist. Dre’s dreams take him in different directions. Life conspires to keep them apart even though they both have a feeling they should be together. The play slides around in time, gradually shading in the losses and challenges they’ve faced along the way, including struggles with mental health, or in Dre’s case, learning how to be a parent. The play leaves a lot unsaid, and constantly tempers its moments of romance with moments of more down-to-earth reality.

The Bush Theatre’s artistic director Lynette Linton directs a slow burning production that allows the relationship space to unfold. The set is a sleek black square lit by strips of neon, the stage naked except for four boxes, which are gradually unpacked to reveal more boxes, with shifts in lighting used to indicate the shifts in time. I could have done with a bit more physical dynamism, but there was an easy warmth to both the performances.

Comparisons have been drawn between this play and Nick Payne’s Constellations, but whereas that play was a tear-machine, Lombe’s play is more subtle, showing how people and relationships can contain multiples. (At the Wednesday matinee I attended it was also sold out, another sign that the Bush Theatre knows its audience).

Foam, Finborough Theatre

The new play by Harry McDonald at the Finborough Theatre, takes inspiration from the double-life of Nicky Crane, a notorious British neo-Nazi who it was later revealed to be gay, dying of an AIDS-related illness in the 1990s. A member of the far-right British Movement, Crane had a reputation for racially motivated violence, including an attack on a Black family at a bus stop, but he also a presence of London’s gay scene, even working security at gay clubs. How did he hold these things together inside himself?

McDonald’s play consists of five encounters, each of which takes places in a public toilet. In the first, a newly shaven-headed teenage Nicky encounters an elegant upper crust type called Mosley (Matthew Baldwin) who wants to recruit him to the cause. Named for, and styled like, Oswald Mosely, the founder of the British Union of Fascists, he is charismatic and seductive, the scene between them capturing the allure of such movements to young men, with their uniform – Mosley gifts Nicky his first pair of bovver boots – and their club-like nature, but there’s also a subversive, sexual element to their encounter, with Mosley bending before Nicky to masochistically lick those boots - and a repulsion/attraction dynamic ripples through the whole play.

In the following scenes, Nicky encounters a young photographer and an amateur porn director, both played by Kishore Walker, both seduced by the image Nicky presents to the world to the point they are able to overlook his beliefs and capacity for violence. Nicky also encounters Bird (Keanu Adolphus Johnson), a young Black man in the gay club where he is working the door. Bird clocks him for what he is, since they served time in the same prison, but is nonetheless intrigued by his duality. Bird advocates using violence against violence to combat fascism, and while they are opposed to everything the other represents, there is a sense of recognition between them. The final scene sees a now physically diminished Nicky in hospital, resisting his lover Craig’s attempts to care for him (Baldwin again, excellent in both roles)

McDonald doesn’t exactly try to solve the puzzle of who Nicky was, he recognises the impossibility of that, rather Foam (it took me an inexcusably long time to figure out why it was called foam) examines the ways in which his queerness co-existed with his Hitler-worship, while also shining a light on subcultural overlap in the 1970s and 80s, and the way some people found the skinhead look exciting and transgressive, a turn on.

The production benefits from a strong performance from Jake Richards as Nicky, combining menace with flashes of real vulnerability, inarticulate belligerence and big kid physicality. Matthew Illife’s production does suffer from pacing issues, with pauses held too long allowing tension to evaporate, but with our politicians using increasingly extremist language, and the far right on the rise everywhere you look, McDonald’s willingness to look hate in the face feels very necessary.

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events over the next seven days.

Macbeth – Following her acclaimed version of Annie Ernaux’s Memoire de Fille, the Italian director Silvia Costa will direct Shakespeare’s play of power and ambition at the Comédie- Française in Paris, where it opens on 26th March.

Malinda – Fritzi Wartenberg returns to the Berliner Ensemble, where amongst other things she previously directed Ella Hickson’s magnificent play The Writer, to direct a new stage version of Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel about a woman - another writer - and her love affairs with two different men. It premieres on 27th March.

Gunter – UK company Dirty Hare made a splash at last year’s Edinburgh Fringe with this atmosphere, music-infused devised show inspired by a true account of 17th century witch trials. The Fringe First-winning show comes to the Jerwood Theatre Upstairs at London’s Royal Court, from 3rd-25th April

Thanks for reading! You can reach me about anything newsletter related on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

"Not everything has to be 3 hours long, Jez" made me laugh