Body songs: Sex Education II and the Mladinsko Theatre showcase

On a multi-part performance exploring female sexual pleasure and Brecht as a blunt instrument.

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

This week in The Stage I interviewed Gemma Whelan, Yara Greyjoy in Game of Thrones, about returning to the stage to play Charlotte Brontë. Following last week’s exploration of Nina Rajić Kranjac’s Angels in America, we’re staying in Slovenia for the remainder of the Mladinsko Theatre Showcase, which included a six-hour exploration of female pleasure and a show based on Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts.

If you find this newsletter enjoyable, interesting or otherwise useful, please do consider sharing, subscribing or, if you are able, becoming a paid supporter. I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to support my writing that way. This newsletter is rewarding and enjoyable to write, but it takes time and effort.

A pool of lube spreads across the floor. It grows in size, forming a gleaming lake. This is the first instalment of Sex Education II, a five-part lecture-theatre series exploring different facets of female pleasure and sexual and reproductive rights, at Slovenia’s Mladinsko Theatre, where it was presented as part of their annual showcase.

The Mladinsko Theatre was founded in 1955 as a youth theatre in Ljubljana. Only during the late 1970s and 1980s, did it start to create work for an adult audience. These days the theatre focuses predominantly on devised and political theatre, and has a recognisable brand of provocative topical work, a prime example being Republic of Slovenia. While it is a state subsidised theatre, its slightly out-of-the-way location and general rebellious energy have more in keeping with an independent space. Under the artistic directorship of Goran Injac, it’s managed to build a reputation as a provocative, adventurous and often explicitly political space. (You can read more about Injac in this piece for SEEstage). I’ve been to several of their showcases, always confident I’ll encounter work that is challenging and adventurous.

Sex Education II certainly feels like something that would have been unlikely to emerge from any other Slovenian institutional space. Created by Tjaša Črnigoj, Lina Akif, Sendi Bakotić, Nika Rozman, Vanda Velagić, Tijana Todorović, Barbara Kapelj, Tea Vidmar, and Lene Lekše, and directed by Črnigoj, the pieces can be performed separately, or as was the case when I saw it, as an almost six-hour marathon at Mladinsko’s New Post Office, a space for smaller-scale performances, which, as the name suggests, is housed in a former post office located a short distance from the main building.

Drawing on interviews with women about their personal experiences as well as contributions from experts, each section of Sex Education II tackles a different topic, the first of which, Diagnosis, concerns the pain that many women experience during intercourse. Under-discussed, misunderstood, and still too often dismissed by medical professionals, this encompasses a spectrum of experiences up to and including vaginismus, a spasming of the pelvic floor muscles which can make vaginal penetration extremely painful and, for some, impossible.

As performer Nika Rozman empties a bottle of lube on the floor, we hear audio of women discussing how their experience of pain have impacted their relationship with their bodies and their partners, and how some doctors still prioritise their partner’s sexual needs over their discomfort, as well as Dr Gabrijela Simetinger, a sexologist who works with women who experience this condition (privately, as it’s not something health insurance covers), encouraging them to gradually become comfortable with their bodies and dealing with them as whole beings rather than malfunctioning parts. A mirror, she informs us, is one of the most useful pieces of equipment in her clinic, Rozman then uses a mirror to reflect images of vaginas of all shapes and sizes on the walls, before stripping to her underwear and skidding and sliding around in the pool of lube. Several times she crashes to the floor, her skin slick with the stuff. It’s at once silly and risky, the perfect performative gesture for the topic in question.

The piece concludes with musician Tea Vidmar using vaginal dilators to create a kind of ululating coda. Throughout the project her music is used to provide an extra layer of sensory texture, whether singing or providing unconventional musical accompaniement.

The second section digs into the issue of consent. We are invited into a different space in the New Post Office building in which a lot of material on the subject is on display on the walls, including a definition of enthusiastic consent. We are presented with video and audio in which women recount sexual encounters in which they felt pressurised to go ahead with things with which they weren’t comfortable and those in which they were clear and firm about their boundaries. We begin seated but are invited to inspect the texts on the walls. A performer begins emptying bags of garden soil on the floor, forming a black carpet in the middle of the room. Clad in a white boiler suit, Rozman uses her body, her hands and her buttocks, to displace some of the soil, via a series of almost ritualistic motions. As Vidmar plucks discordantly at the innards of piano, the word consentire is written in the dirt.

For the third section, entitled Ability, we are seated in a more conventional end-on fashion, for an exploration of the experiences of women with various physical disabilities of intimacy, desire and dating. One woman with a degenerative condition describes how she maintains a healthy sex life with her husband that satisfies her sexual appetite even as mobility decreases. Another describes her journey to regaining her confidence after a spinal injury, while another discusses the experience of using dating apps when you have a visible limb difference. Though we hear their voices, the women are represented by a series of pen drawings on overhead projectors by performer. We also hear from a care agency who work with people, including those with learning disabilities, who require assistance to manage their sex live. We do not hear from anyone who requires carer assistance, however, which feels like an omission from a show thar is otherwise generally careful and inclusive. (Personally, I would have valued more lesbian and queer voices too, though there were a few).

The fourth section (following a lunch break) is called Play and is about the role that fantasy, fetish and kink can play in the bedroom. It's formally much looser and more exuberant than the previous sections with Akif, now dressed in a gown and a rebellious wig, introducing us to the art of shibari, Japanese rope play, before escorting us into a neon-splashed space where we hear from women who enjoy being dominated, sex party attendees and and those who adopt ‘furry’ animal personas online.

The last piece, entitled Fight, transports us to yet another space in the New Post Office building and, also, back in time, to the former Yugoslavia. The piece, performed by Croatian actors Croatian Sendi Bakotić and Vanda Velagić, begins with a trip into the concrete underbelly of the building for a discussion of methods of underground abortion, before heading upstairs for a history lesson on women’s reproductive rights in the former Yugoslavia. Abortion was a pressing societal issue after the Second World War, with women often dying from botched backstreet procedures. Later, they soak underwear in red dye and string them from a washing line.

The core of the show explores how politician Vida Tomšič and gynaecologist Dr Franc Novak, campaigned for family planning as a human right in what was then Yugoslavia. Bakotić and Velagić detail their quest to find out more about Yugoslav-produced diaphragms and we follow their journey through the archives to track down the little rings of rubber that transformed so many women’s lives.

As fascinating as it is as a history lesson, it hits all the harder given the alarming way in which women’s reproductive rights are being rolled back. We watched this piece shortly after the French voted to make terminating a pregnancy a “guaranteed freedom” in the constitution, which was reported in some quarters as a first. However, as other people – including this article –were quick to point out it was enshrined in the constitution of the SFR Yugoslavia in 1974.

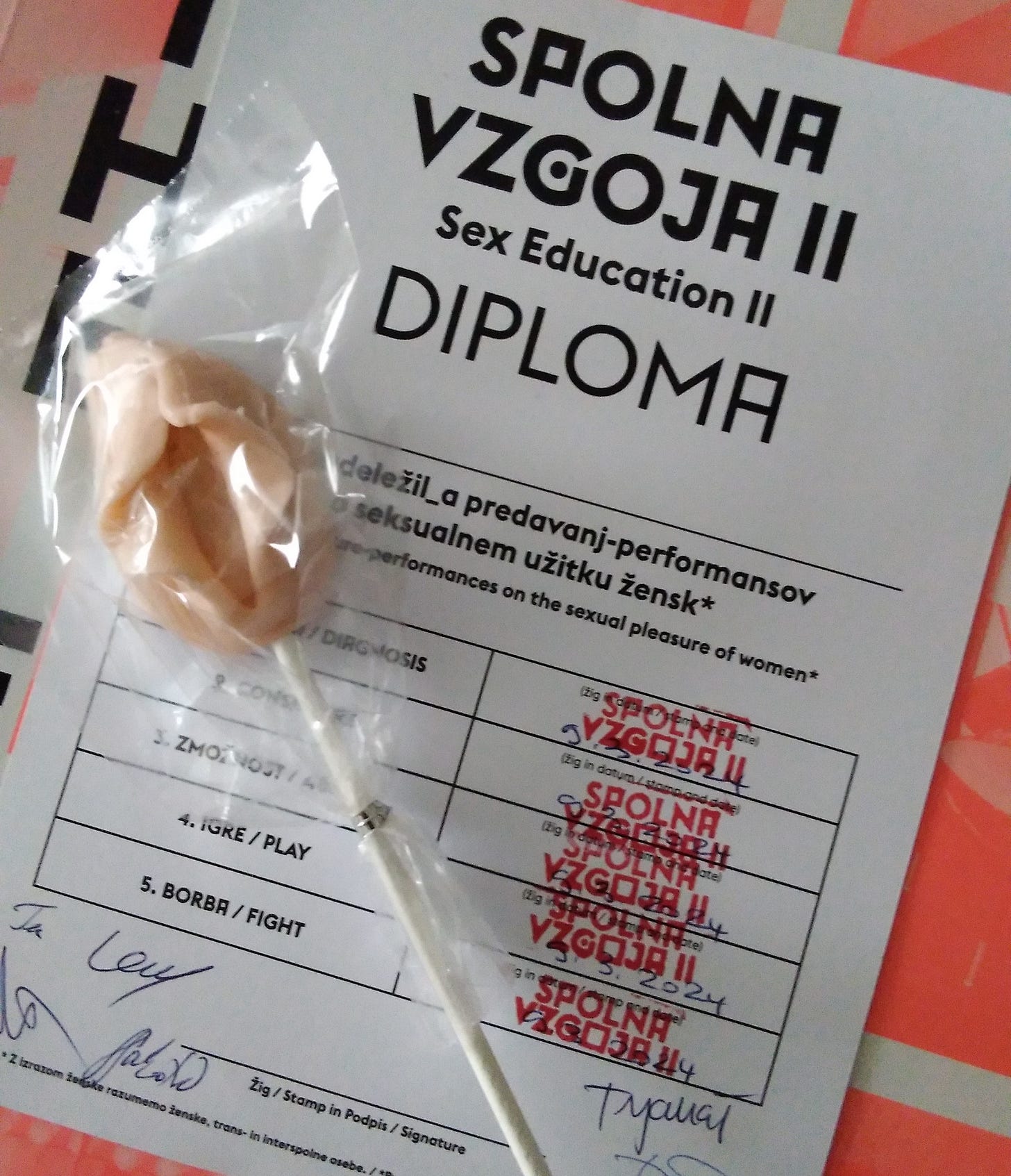

While the Fight section would work as a stand-alone show, watching it as the cumulation of this bigger experience how much of women’s experience of desire, pleasure and pain has been relegated to sidebar if it is discussed or acknowledged at all. There was a genuine thrill to having this much space made for these topics to be explored in depth and detail (plus we got a vulva lolly).

Family portraits: The Argonauts

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts is a mix of memoir and refection on motherhood, family, pregnancy and her relationship with the trans artist Harry Dodge. Polish director Michał Borczuch and adaptor Tomasz Śpiewak have spliced Nelson’s book with material from interviews conducted by the actors of the show. The subjects of these interviews were all involved in some non-heteronormative relationship, a young trans individual and their girlfriend, an older male gay married couple. These interviews are recreated by the performers on stage. Maggie is often seated at her kitchen table, writing away or reading from her work. Some of the ideas raised are radical and fascinating, like the idea of pregnancy as a fundamentally queer experience.

Two platforms have been erected at the front of the stage, which designer Dorota Nawrot had populated with stained glass windows, including one featuring a vial of testosterone (which for me brought to mind Polish dramatist and stained-glass artist Stanislaw Wyspianski).

There’s a lot of discussion about gender and transformation, the weight of public perception and prejudice faced by non-heteronormative families, and what it is to love and live outside societal expectations. Damjana Černe plays an AI who talks about self-love and liberating nature of the single woman, with the road ahead of her.

The interview sequences feel rambling, a feeling perhaps heightened by watching it directly after Sex Education II (literally, we had about a 15 minute break before the next show started) which wove interview material into the show with clarity and care. The scenes between Nelson, Harry and their family meander too - for a while they just hang out eating noodles - and not in a way that feels controlled or meaningful.

Not everything needs to be fast-paced and confrontational, and maybe this says something about my attention span, but I found it a bit of theatrically underpower, though I did come away determined to read the book, to absorb more of Nelson’s ideas.

Laughter and loathing: Fear and Misery of the Third Reich

Sebastijan Horvat is a director fond of disruption. In his version of Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (which I keep finding myself talking about years later), the audience is invited to help construct the set during the interval and ends sitting knee-to-knee with each other within the set as the play continues around them. He recently directed a bold three-part production of Heiner Muller’s Cement in which the text was fractured into three parts and performed with three separate ensembles in the three different cities, at SNG Drama Ljubljana, Zagreb Youth Theatre (ZKM) and Belgrade Drama Theatre, each part significantly different in form (more on this project in this interview). He has such an exciting theatre brain, that when the first third of his production of Brecht’s Fear and Misery of the Third Reich turned out to be fairly traditional in delivery, I found myself waiting for a rug-pull.

The show was performed in Kino Šiška, a super-cool cinema turned music venue and performance space. The audience was seated around a catwalk-style stage. As I said, the first scenes of Brecht’s 1938 text a series of playlets, felt like the kind of thing you could see anywhere. There are title cards and period-appropriate costumes, a rendition of O Tannenbaum juxtaposed with casual cruelty.

Then, roughly half way through, we shift to a more recognisably contemporary setting. A white family are sitting down to dinner when an immigrant - Lina Akif – appears at their door. They fall over themselves to feed her and provide for her, as she grows increasingly demanding, helping herself first to their food, then to their phones, forcing them to dance awkwardly before eventually stabbing one of them.

When talking about this performance ahead of the premiere, Horvat described it as a piece “about fascism today, about populism and the far right” and the way far right movements have “appropriated the concepts of transgression and counterculture.”

A sense of cultural-flipping and mirror-lifting is very much on display. There is fiddle-playing and there is vigorous, shirtless dancing; there is a monologue from one of the actors railing against the tyranny and exploitative nature of the devising process. A golden pig is hefted on stage, and the cast take turns fingering its anus. People cavort in SS caps and feather boas. It is grotesque and excessive, carnivalesque, a lot more in keeping with contemporary theatrical tastes, with a dash of parody of Mladinsko’s own mode of making work thrown in for good measure.

The show concludes with an extended scene featuring Stane Tomazin. While the Mladinsko ensemble are all comfortable and capable of using bodies as instruments, Tomazin frequently stands out for his comic skills - a bone-deep understanding of how to draw a laugh - his versaility and his sense of utter fearlessness.

In the 10-hour no title yet, (which I wrote about previously here), he turned a comic side-character into a monumental study of ego and the complex power dynamics that characterise the actor-director relationship while variously wearing a black crochet dress and lip-syncing to Nick Cave or slathering his naked body in Slovenian cream-cake while skidding around on plastic sheeting. As Louis in Angels in America, he engaged in tender yet ravenous outdoor love scene with another man, fully naked despite the chilly spring air. In Horvat’s production, he stands before us on stage, a cis white man, and starts talking about permissibility, who gets to say what. He recognises that what he’s saying is problematic and sashays off stage, returning with his T-shirt rolled up, a crude stereotype of a gay man. Again, he backs himself into a cul-de-sac and returns in a wig and heels, as a “trans bisexual woman.” This process is repeated several times over until he is rolled on stage in a wheelchair, aping the gestures of someone with learning disabilities, with smears of black paint on his face. By the end of the show, he is covered in beer and tomato sauce.

This is something I found hard not to view through a British lens, specifically the whole sequence made me think of Little Britain, a UK television sketch show that occupied a primetime slot in the 2000s, written and performed by Matt Lucas and the charm vacuum that is David Walliams, which was stuffed with caricatures of working class, women of colour. Ugly, ugly stuff that percolated into the playground. Now, Horvat is obviously using these tactics to poke at several nests here, using Tomazin’s charm and comic skills as a weapon, generating laughter (uneasy at first, but increasingly more fulsome) about transgression and offence, at the saying of the ‘unsayable.’

Occasionally during this process you’ll see a flash of distress in Tomazin’s eyes – “I’m definitely going to hell,” he mutters at one point. This sense of internal ethical wrestling was in some ways more interesting than this parade of grotesquery. Watching someone cross a moral line in front of your eyes is fascinating and I wish the production had delved more into this.

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events over the next seven days

The Welkin – Staying with Sebastijan Horvat, his next project is a production of Lucy Kirkwood’s 2020 play about a young woman in 18th century Suffolk accused of murder, whose fate - and whose pregnancy - must be decided by a jury of women. It premieres at SNG Drama Ljubljana on 23rd March.

They – It’s now possible to watch Maxine Peake, Sarah Frankcom and Imogen Knight’s collaboration from last year’s Manchester International Festival, an adaptation of Kay Dick’s 1977 dystopian novel They: A Sequence of Unease - set in a world where art is being eradicated - on demand until May.

I’m a Girl You Can Hold IRL – Young novelist and playwright Zelal Yeşilyurt’s new play explores sex, loneliness and robotics in a modern Pygmalion tale which premieres at Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theatre on the 23rd Match.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, thoughts or other comments you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com