Art can't heal you: Revisiting Carolina Bianchi's The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella

On rewatching a potent show about femicide and sexual violence.

Recently I’ve had the opportunity to rewatch a number of productions I’ve seen over the last couple of years, something I rarely get to do. One of the shows I was most keen to see again in a different context was Carolina Bianchi’s Cadela Força Trilogy - Chapter I: The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella, a piece I first saw - and wrote about - in Vienna earlier this year It’s a show I’ve been thinking about a lot since I saw it, so I welcomed the chance to revisit it, to explore how and if my feelings towards it had shifted, and to talk to Bianchi about the work.

Café Europa is free to read and it’s important to me that it stays that way, but it takes time to research and write, so if you find it valuable and would like to help support my writing, you can do so by becoming a paid subscriber or just help spread the word by sharing it with others who might like it.

The word ‘controversial’ has become attached to Carolina Bianchi’s The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella, the first part in her Cadela Força trilogy. It was deemed “ethically murky” by the New York Times and, in Australia, it was almost eclipsed by a debate over whether the show was even legal. All of this obscures what the show is doing. Yes, the show is in no way an easy watch. Yes. It makes audiences uncomfortable, but it should. This is a show about the way violence against women, sexual violence in particular, is baked into our culture, how femicide is endemic, how we live in a world where a man can go on an internet forum and invite people to rape his drugged and unconscious wife and over 50 men will eagerly agree to do so. It should make us fucking uncomfortable.

Watching the show for the second time, I was struck even more than before how this is a piece that locates itself at the juncture between performance art and theatre, how this is at once a piece in which the artist’s body is the medium and a highly in-demand piece of theatre which has been performed all over the world. While Marina Abramović and other artists have recreated key pieces of their work for retrospectives, Bianchi, whose background is in theatre, is engaged in a constant process of revival with this piece - and, I’d argue, ritual.

The show’s key gesture, in which she takes a drug on stage and then slowly succumbs to in front of the audience, is something Bianchi points out she is not the first to do. She’s following in the footsteps of others, locating her work in an artistic continuum. It’s also just one element, albeit a central one, in an almost two-and-half-hour long show in which a lot of other stuff happens.

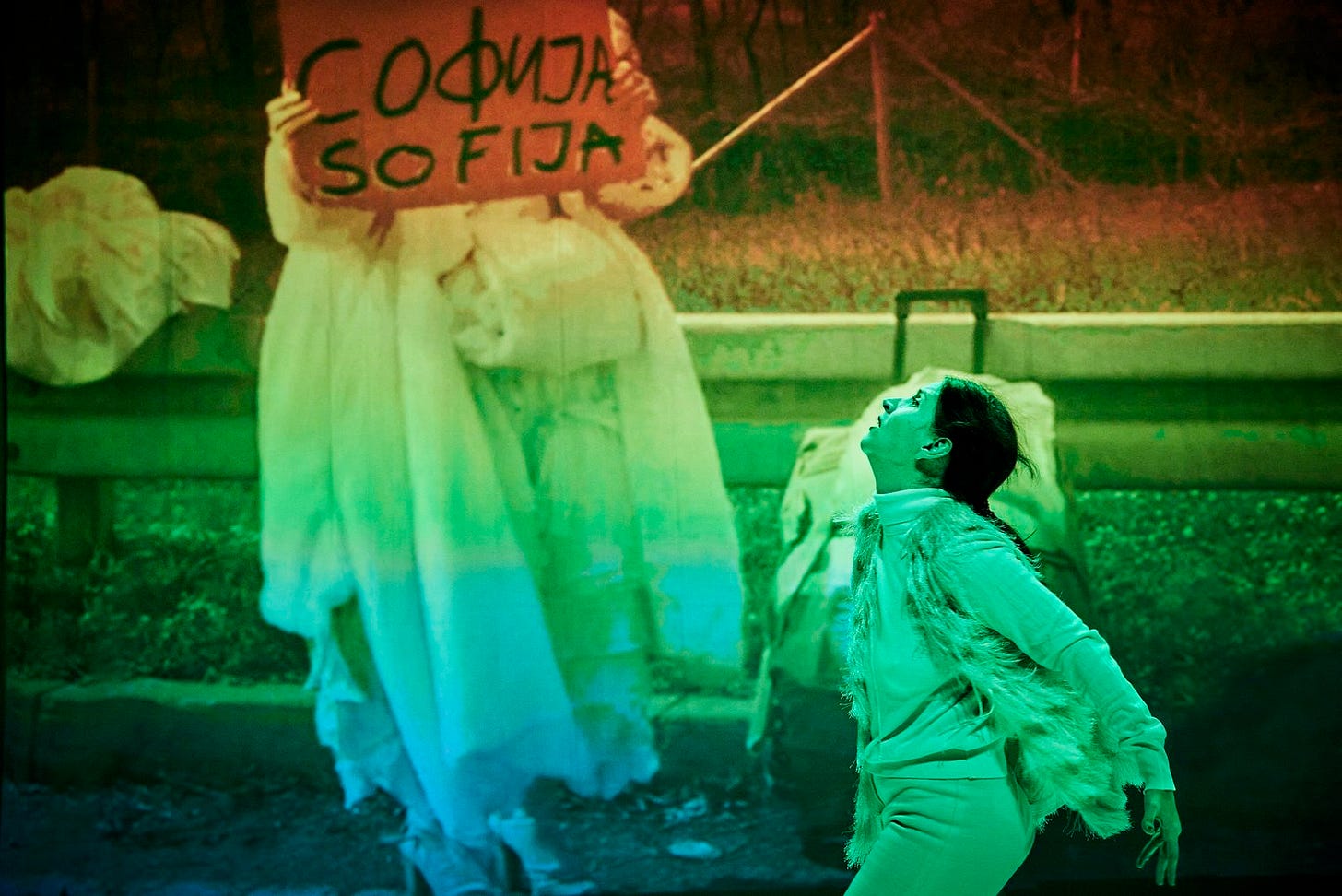

The first half is often described as lecture-theatre. Bianchi sits at a desk with her notes in front of her and mixes herself a vodka and tonic into which she pours a baggy of white powder. There is also a candle on the table and a mound of earth under the desk that resembles a grave. Bathed in sickly green light, it feels like she is mixing a potion, casting a spell.

During this section, which also includes explorations of violence against women as depicted in renaissance art, Bianchi describes her fascination with Pippa Bacca, the Italian performance artist who, along with her collaborator Silvia Moro, planned a piece called Brides on Tour, in which they would hitchhike across the Balkans and the Middle East while wearing wedding dresses. The piece was intended to promote world peace, but at some point, Moro and Bacca parted ways. The original idea was for them to travel with whoever stopped to pick them up, but Moro expressed reluctance to do this and Bacca continued alone. She was later raped and murdered somewhere near Istanbul. (In a grim twist, Bacca’s killer would take her stolen camera to a wedding and use it to take pictures of the bride’s face).

Bianchi goes on to talk about other artists, in particular about Ana Mendieta, who died in 1985 at the age of 36, when she fell from her 34th-storey flat after an argument with her husband, the sculptor Carl Andre. She talks about Tania Bruguer, who put a loaded gun to her head and pulled the trigger in a piece called ‘auto-sabotage.’ She talks about her own practice and how she explored different performative avenues, including cutting words into her own thigh. But she keeps circling back to Bacca. She despises her for her naivete, for her internalised patriarchal ideas about purity, motherhood and womanhood, for her faith that her white dress would shield her form the violence of men. I had forgotten how furious she is in this moment, how scornful, not just of Bacca but at a form of feminism that thinks solidarity will ever be enough in the face of such violence.

(As she launches into a ferocious, full-throttle karaoke performance, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t wonder about the choreography of this moment - which is amazing - about how much of the lurching and unsteadiness is down to her skill as a performer as well as being a result of whatever she has ingested).

One of the criticisms that is made of the show is that it loses something after Bianchi falls asleep and the stage is overtaken by the eight performers from the Brazilian Cara de Cavalo collective. That it becomes baggier. That it lacks the rigour of the earlier scenes. There is truth in this. It does lose something. But it also needs to, it has to. For the remainder of the show, until her groggy reawakening, Bianchi is at once absent and present. Her body is there, head lolling and limbs bare, but we miss her. We miss her charismatic, magnetic and assured presence on stage. We miss her clarity and vehemence. Her voice remains with us in the form of text displayed on a screen at the back of the stage, but it is disembodied, an interior monologue. This text continues to describe different forms of violence and violation, detailing an appalling crime committed by a Brazilian footballer against the woman who had his child (a crime which barely seemed to dent his popularity in his home country) and discussing a section of Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666 in which he describes the murders of more than 100 women and girls between 1993 and 1997 in Mexico.

These scenes are intended to be Dante-esque, a plunge into the abyss, a hazy dream-space in which Bianchi’s body drifts while surrounded by woozy, boozy, sticky-skinned dancers, but these scenes are also marked by a degree of care. There is care in the way her troupe cradle and carry her, tenderness in the way they place in her in the boot of a car, and exceptional gentleness in the way they later lift her onto the bonnet of the same car, spread her legs and insert a camera into her vagina as if giving her a gynaecological examination. The footage is projected onto a screen as the camera probes inside her. It is deeply intrusive and yet weirdly intimate. It captures the cold, clinical nature of an examination carried out after a sexual assault as well as being an enormous act of trust between Bianchi and her troupe.

The show also speaks of memory and how date rape drugs can rob you of your ability to remember what happened to you and your body, leaving behind holes that are difficult to fill, terrible expanses of unknowing. In this context, the focus on recreation and re-enactment makes even more sense, albeit in the grimmest of ways.

Watching the show again, I also found myself wondering about both the psychological and physical toll of performing it repeatedly in front of international festival audiences for well over a year now. Obviously Bianchi is an artist how has spent years working on this piece and thinking deeply about this stuff and yet she cannot have anticipated this show becoming such a phenomenon, a piece that every festival wants to programme. Does that reshape your relationship with the material? (Or is this a banal question to ask?)

This is a show that raises so many questions about the relationship between art and harm and violence and the body, about self-destructive impulses and the erasure of self. It actively resists providing answers and yet its moral stance is never in doubt.

When I watched it for first time I remember feeling her absence keenly in the second half. I remember even being a little bored towards the end, but on rewatching it, this imbalance feels fundamental to what the piece is doing. It needs to lose its way a little. And while the moment of her waking, her gradual return to the world, has real power it also comes with the understanding that everything we’ve witnessed will happen again.

“A performative act inside a theatre piece” - An interview with Carolina Bianchi

Carolina Bianchi is not from a performance art background. “My background is in theatre, completely,” she explains to me backstage at the Terazije Theatre in Belgrade, where she will perform later that evening. She actually started out as an actor, she says. “though writing was always part of my practice.”

When still in Brazil, she made work that touched on the topics of sexual violence – including a 2018 show called Lobo (Wolf) inspired by the life of the Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who was raped as a teenager. The work was theatrical, whereas The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella very explicitly locates itself in the arena of performance art. What prompted this shift in her practice?

Having moved to Amsterdam in 2020 to complete her Masters’ studies, Bianchi became “completely obsessed” with the story of Pippa Bacca and the fact she died in the process of making “a performance that also talks about hope and kindness and hospitality, that shows how human beings can be good in any circumstances.”

To make a show about Bacca’s art and death, she realised she needed to connect her artistic practice with Bacca in a direct way, “in order to be close to her.” Bianchi started to research the art of other female performers who explored violence in their work, and often connected that violence with their own bodies. She studied the work of Marina Abramović, Ana Mendieta and Regina Jose Galindo.

“It was important to be able to see whether people like Bacca could be placed inside this genealogy or not,” she says, to place a frame around this work. At the same time, Bianchi was thinking about how to "apply myself as a performer inside of this work.” She wanted to create a piece of performance art that contained “a strong gesture of the body,” and eventually alighted on the concept of taking this drug on stage.

Key to the piece is the idea that, by performing this gesture, by ingesting this drug, “there is something that is lost.” Something needed to disappear inside the show, she explains, and taking the drug is “my gesture of disappearing,” It's something concrete, she adds. “It's not only a metaphorical disappearance, but also the disappearance of the conscious woman who is guiding you on this journey.” Bianchi is the only figure on stage for the first half of the performance. She commands the audience’s attention and then she falls asleep - she disappears. The taking of the drug is also, she says, “a way of looping myself and my personal history into the show.”

Brazil has one of the highest rates of femicide in the world. The show describes some horrific incidents of violence against women and the culture in which the perpetrators not only escape punishment but are often valorised. The issue of femicide and male violence is, of course, not limited to Brazil. Men murder women with depressing regularity all over the word. The show has proved resonant wherever it plays, including Serbia, where men who murder partners or female family members are often given lenient sentences. It is also a country, as Bianchi points out, living with the legacy of weaponised rape during the war.

Part of the show’s development took place in Belgrade. While she was studying in Amsterdam, Bianchi became friends with Andrej Nosov, the director of Serbian NGO and theatre production company, Heartefact. Nosov was there at of the earliest presentations of the piece in 2021, part of an audience of only eight people due to Covid restrictions. This was the first time Bianchi had ever taken the date rape drug in front of an audience and explored what it did to her body. Having watched the performance, Nosov invited her to Serbia for a residency during Heartefact’s Pride Festival, which takes place during Pride Week in Belgrade. This was, she says, “a really strong experience for me, because I made a lot of connections between Sao Paulo, where I was living before, and Belgrade.”

Since the show premiered in Avignon last July, it has played festivals around the world. It’s the kind of trajectory it’s impossible to anticipate an artist. It’s the kind of success that can also exert a toll and bring its own set of pressures. Working together with people she trusts helps, she says in this respect, “in the sense of being able to do what you want to do and not what people expect you to do. Having worked for a long time in Brazil on the independent scene, she now has institutional support for the first time in her career.

The trilogy will continue with The Brotherhood which will explore “masculinity pacts”, the codes and connections that exist between men and the role that sexual violence plays in them. This second chapter, which Bianchi says will move away from the performance art arena back to something more theatrical, will premiere at KVS in Brussels in May next year.

Bianchi was also supported in making the piece by Carolina Mendonça, her dramaturg and partner in this research process. It feels like this relationship is vital. They have been friends for 20 years, and Bianchi thinks the fact they have a shared need to talk about this kind of violence and trauma has made the process “less lonely.” Making this project has been a process with two layers, she explains, “combining a very lonely process with a very collective one.”

The production has received acclaim and awards since its premiere including the French Critics’ Syndicate Award for Best Foreign Premiere in the 2023/2024 theatre season and the Jovan Ćirilov Special Award at this year’s BITEF. But there has also been pushback. There have been walkouts and incidents of audience members passing out, though Bianchi was impressed that one woman who fainted in Vienna came right back in again to watch the end of the show. In Australia earlier this year, where Bianchi performed at the Rising Festival in Melbourne, things went even further. In addition to handwringing in the media about the show’s content, legal concerns were raised that the show might even be in breach of Victoria’s strict consent laws. Despite this, says Bianchi, the audience response was warm and supportive. “The experience with the audience in Melbourne was so beautiful. It was almost like a kind of revenge to the situation. It was really welcoming, and we had one of the best reviews of the story of our show there.”

While the incident in Australia is the most extreme, touring a show like this presents its own challenges, both to them as a company and to the programmers. Her producer says they deal with this by imbedding explanations both inside the work and externally, explaining what happens during the performance and being clear in their communications with publicity departments and with the press. “It's a performative act inside of a theatre piece,” says Bianchi. They are still coming to grips with what it means to repeat this on stage in different cities and contexts. “I think everybody is learning, in a way, us, the producers, the houses, the festivals.”

The show’s key statement – written on the number plate of the car that we see in the second part of the show is: Fuck catharsis. This feels like the show’s mantra. “This kind of trauma of sexual violence cannot be solved,” she says. “You can’t just say: I’m done with this now.” She describes the trauma as a wound that can “transform itself so it’s not always the same shape. It changes. It can move.” The idea that she’s doing this show as an act of healing or release is something she rejects. “I'm really against this,” she says. “I'm strong in my opinions about this. I don’t believe that this can heal you,” she continues.

“With people who suffer traumas, there is an expectation that for you to be accepted in society again, you need to heal.” There is a tendency to place a time limit on trauma. To continue to talk about it eventually becomes less and less acceptable. Catharsis as a kind of purging, an expulsion, is a term that comes from theatre, and Bianchi does not deny that the show contains some element of catharsis. “It can be felt in the show,” she says, “but for me, there is a refusal to go to this place.”

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days

Void – In a move away from Ultima Vez’s more familiar, extravagant style, choreographer Wim Vandekeybus’ comparatively minimalist new show will, apparently, centre those who live outside societal norms. It premieres at KVS in Brussels on 23rd October.

Wasteland: Peter Pan - Director Jessica Weisskirchen and author Patty Kim Hamilton – recently shortlisted for the Papatango Prize for her play Peeling Oranges; – draw out the darkness in JM Barrie's classic to reimagine it as a dystopia. It premieres at Deutsches Theater in Berlin on 25th October.

Kosovo/Albania Theatre Showcase - Having been held in Prishtina for the past six years, the annual showcase of Kosovo theatre relocates to Tirana in Albania, that sees organizers Qendra Multimedia joining forces with the National Theatre in Tirana and the National Experimental Theatre to present a mixed programme of Kosovan and Albanian theatre to an international audience. The showcase takes place between 29th October-2nd November.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com

Oh my what an article! Natasha you've done it again - it made me want to hop on a plane to come be an audience member for this. It brought up so many questions about the piece, the artist and also my approach to art. Thanks so much for what you do and how you share your passion for performance and how it can affect us. Take care!