A plea for change: How Prima Facie became an international phenomenon

On the rise and rise of Suzie Miller's one-woman play about the ways in which the legal system fails victims of rape.

Welcome to Café Europa, a weekly newsletter dedicated to European theatre.

Hello to everyone who found their way here via last week’s edition on the making of Three Kingdoms. I try and offer a mix of reviews, artist profiles, festival coverage and topic-driven pieces, like this one on an artist’s “right to fail.” This week, in order to mix things up a bit, I’m profiling not a person, but a play.

Some plays capture the collective imagination. Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs is one - it feels like every other theatre in Europe has a production in the repertoire. Now Prima Facie, a one-woman play by Australian lawyer-turned-playwright Suzie Miller about the ways in which the legal system fails victims of rape, has with productions proliferating across Europe

Following its 2018 premiere in Australia and its triumphant production in London’s West End, Prima Facie has been licenced in 32 countries, with versions of the play opening in late 2023 and early 2024 in Germany, Austria, France, Spain, Poland, Czech Republic, Holland, Hungary, Iceland, Belgium, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Serbia, and China. There are more productions to come. The National Theatre of Finland production opens in April.

Prima Facie’s protagonist Tessa, a confident young barrister with a career in ascendent who suddenly finds herself on the other side of the system after she is raped by a colleague. Miller drew on her experiences as a criminal defence lawyer. “I just didn’t believe in the system,” she said in a piece in Guardian Australia. “The one area that I think they’ve got wrong, really wrong, is consent, lack of that, and believing women.”

The play had its premiere at Sydney’s Stables Theatre in 2019, produced by the Griffin Theatre Company with actor Sheridan Harbridge playing Tessa. In its review of the play, The Conversation wrote that “it is a voice of steely reckoning that contains within its very timbre the rage of being a woman.” The Sydney Morning Herald called it “an impassioned plea for long-overdue change.”

The London production, which opened in April 2022, starred Jodie Comer – star of Killing Eve - and it’s hard to convey how good she was in what was basically her stage debut. She starts out exuding confidence as the young barrister making a name for herself; she gives the appearance of someone whose belief in themselves is matched only by her unshakeable belief in the law. She describes the law as a horse race, herself and her fellow barristers as thoroughbreds. Comer bounds on top of her desk, capturing the thrill of the race.

We get flashes of another side of her in scenes with her mother, with Comer subtly codeswitching to illustrate the fact that the character comes from a different background to her privately educated colleagues. She does an excellent impression of them, however, and Tessa has no qualms about taking a rape victim apart on the stand. Emotion doesn’t come into it. “It’s the game,” she says.

Then a boozy night with a colleague whom she has previously slept with tips into horror, as he rapes her, ignoring her protestations, and she awakes to the realisation of what has happened to her. It goes beyond the act of physical violation; her whole sense of who she is has been shaken. He has taken something from her, and she is fundamentally altered. In Justin Martin’s production, a rain machine is used to accentuate this shift, leaving Comer drenched.

Tessa decides to go police, where she has to deal with all the various indignities of being questioned, probed and examined, of having to submit to people’s hands and to their scrutiny of her life, her memory, her body. In my review for The Stage, I wrote: “Miller’s play spends as much time detailing the aftermath of the assault as the build-up. We follow Tessa through the whole humiliating process: her body made a crime scene, her sexual past scrutinised, her testimony pulled apart.”

A digital display on the back wall makes clear the devastating delay between deciding to press charges and going to court, a problem in the UK court system where a backlog was only exacerbated by the pandemic, leading to people living in a kind of miserable limbo for even longer than was necessary.

The character of Tessa is transformed by her experiences and Comer captures this magnificently. She is vigorous and stage-filling in the beginning, but after her assault she is exposed and vulnerable but also determined to see this thing through the system.

UK critics were almost universal in their praise of Comer, with Sarah Crompton at WhatsOnStage, and Dominic Maxwell at the Times, among those writing glowingly about her, but some critics were a bit more sniffy about the play’s use of “righteous polemic.” It was called “preachy” and accused of being “soapbox theatre.” This was quite a difference to the way it was received in Australia. The play was never shy about its campaigning nature – the Guardian published this roundtable between Miller, Comer, a barrister and police officer about the way sexual assault cases are treated by the legal system. I do wonder if there’s something particularly British in this resistance, in regarding the play’s drum-banging nature as a mark against it.

Since them the play has only gathered momentum. The London production transferred to Broadway, where Comer picked up a Tony Award to add to her Olivier. It was revived in Australia and new productions started to open all over Europe. Miller wrote a novelisation of the play; Comer is due to narrate the audiobook.

Why has this play taken off in such a spectacular fashion? There are no doubt pragmatic factors. It’s a one-person show, and therefor not overly costly to stage, and the character of Tessa is a corker of a role for a female performer, running through the whole emotional gamut. But, of course, it goes deeper than that. The play is a reminder that the MeToo movement did not create much in the way of systemic change, that in many places rape and sexual assault are still things to be swept under the carpet, that the systems ostensibly there to help victims often retraumatise them, and even if a rape case makes it to court, the chances of a successful prosecution remain low. It’s a play that doesn’t just acknowledge the endemic nature of sexual assault, it writes it into the text. Towards the end, Tessa encourages the audience to look first to their left and then to their right and think about how many women in the audience, statistically, will have suffered some form of sexual assault. The figures are grim. One in three women globally will be subject to some form of sexual assault in their lifetime. Miller’s approach might be blunt but it’s a very effective way of underscoring this point.

“It is important that men also speak out”

Hungarian director András Dömötör’s production for Berlin’s Deutsches Theater was one of many to open last autumn. It premiered in September and stars Mercy Dorcas Otieno as Tessa. It was shocking to face, says Dömötör’, how many women he knew had been raped or abused by men. “In Hungary, which is an even more patriarchal country than many West European ones, they are afraid to go the police as they fear not being believed and they don’t dare to risk their reputation.” It was his anger at this that fuelled him to direct Miller’s play. “It is important that men like me also speak out loud that this must be changed.”

Eline Arbo’s Dutch touring production of Prima Facie premiered in November and will be touring the Netherlands until the summer. The artistic director of Internationaal Theatre Amsterdam directed Maria Kraakman in the role Tessa. Arbo has said of the play, “in the Netherlands, we are lagging behind in protecting victims of sexual abuse. Prima Facie is a piece that is brilliantly exposes how the centuries-old legal system is maintained and who is actually protected by our laws."

Arbo’s production features two desks, one on either side of the stage which are used in a variety of ways (one of them even conceals a toilet bowl, into which Tessa will later heave). The stage is surrounded on three sides by white frames from which pieces of paper are suspended – these pieces of paper, each one representing some woman’s case file, come into their own at the end of the show. Kraakman gives a commanding performance, every inch the confident professional at the start, a woman comfortable taking up space. The scene of her assault and its aftermath is drawn out, as she groggily strips off her clothes until she is wearing only her underwear, rolling across the stage, hunching over a toilet, utterly exposed, before redressing herself in a shapeless t-shirt and shorts, looking smaller than before.

“What happened to her is something no one should have to abide”

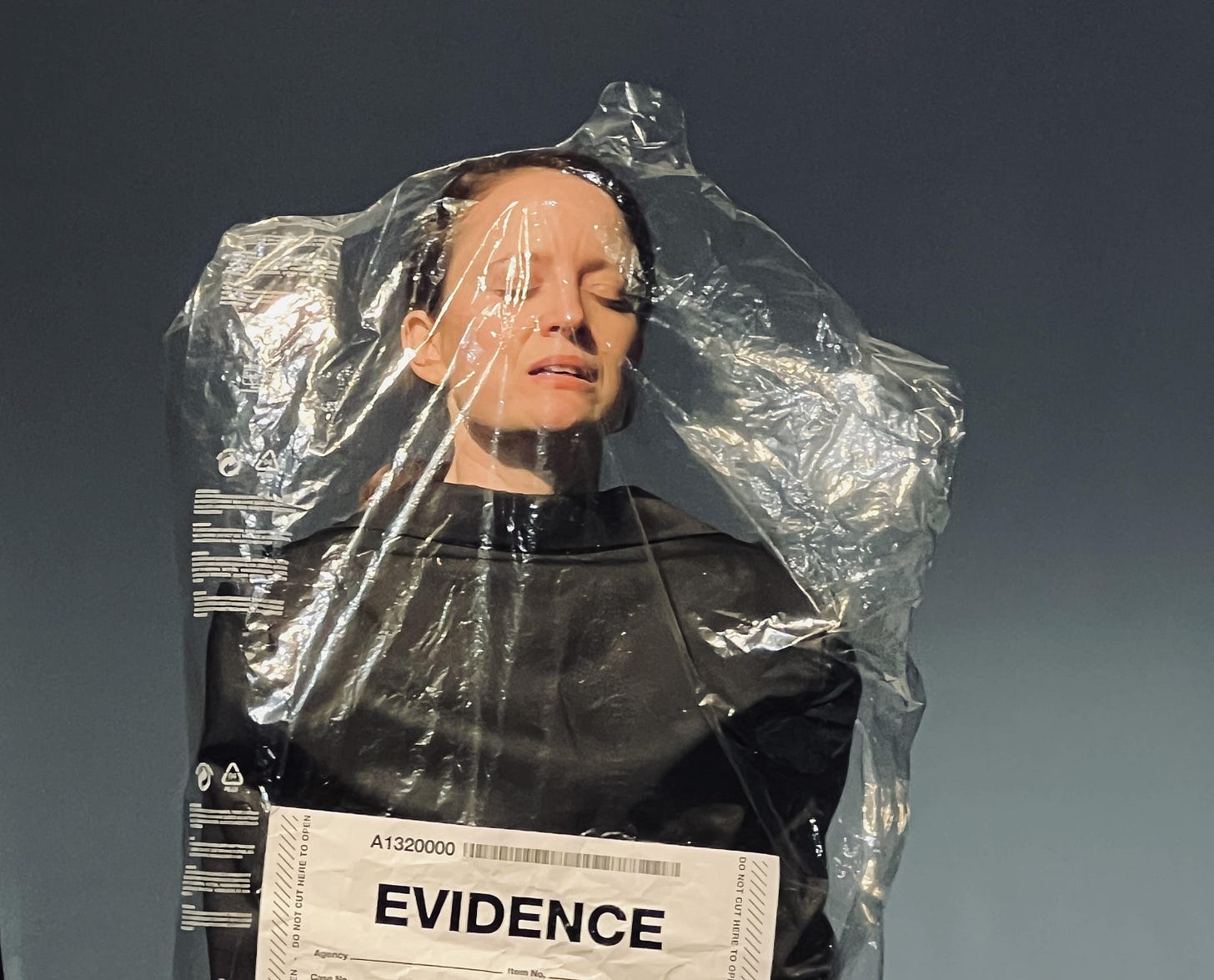

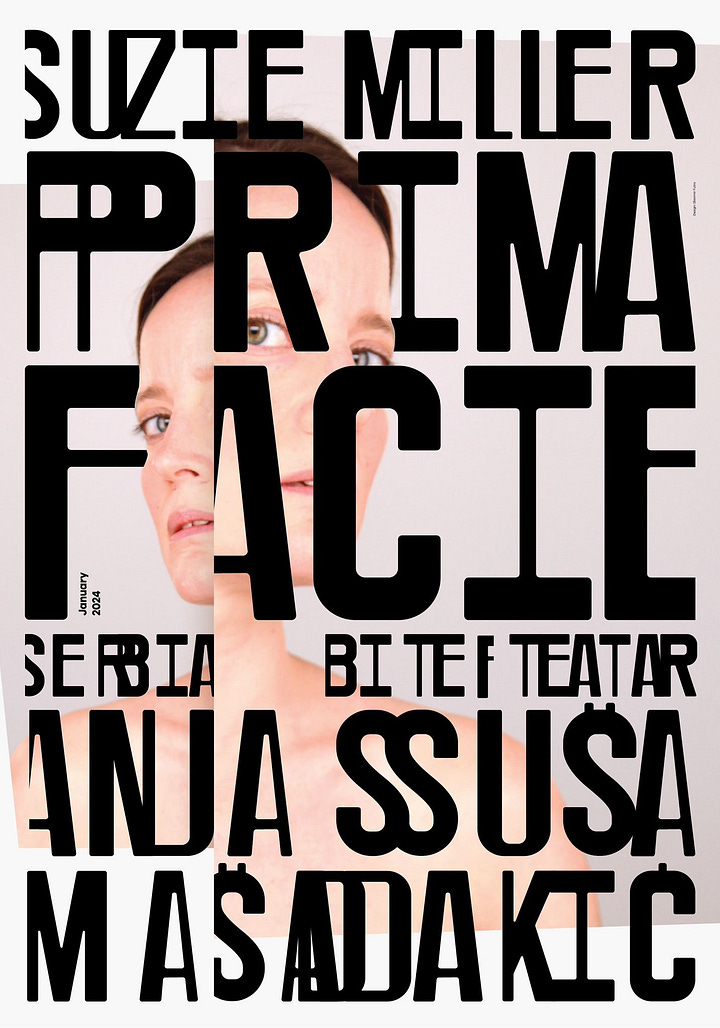

The Serbian production is directed by Anja Suša, one of the region’s best-known directors and a former curator of Belgrade International Theatre Festival (BITEF) and Maša Dakić plays Tessa. It opened at the end of January at the Bitef Teatar, a building which was originally constructed as a church and has a suitably imposing atmosphere. Suša places 12 empty chairs on one side of the stage, an invisible jury – with the audience, one could argue, serving a similar role. She really leans into the idea of the body-as-crime-scene, with a metal autopsy table on one side of the stage, and clothing in evidence bags. At one point, Dakić puts one of these over her head. Strips of white laminate plastic descend from the ceiling and extend across the floor. Dakić is nimble and vigorous, all swagger to start with, delivering Tessa’s opening ‘racing’ speech into a microphone at breakneck speed.

Playing Tessa, says Dakić, “enabled me to use so many tools as an actress, but also encouraged me to explore so much of who I am and how I communicate, even in every-day situations. She has given me so much dignity, so much courage and a sense of enjoyment in being a woman that I haven’t felt before, not on stage nor in life. I feel lucky and grateful in so many ways, that I got to be the Serbian version of Tessa.”

When she’s on stage, says Dakić, “she tries to portray the smile we see in women all the time. But, oftentimes, there’s something behind it that reflects an entirely different emotion.” Dakić also singles out movement director Damjan Kecojević for his choreography of the hospital examination scene, though costume also plays a role with Dakić variously wearing an almost comically outsized puffy coat and a backward suit jacket.

Miller’s text, she says, is “storytelling at its best, fuelled by her legal knowledge and insight, so that you are educated without it being preachy.” What impact has the play had on a Serbian audience? Dakić tells me that after one performance, a young woman told her that “she thought the people in the audience felt more receptive to the topic than maybe a few years back, before these big sexual assault cases in Serbia saw the light of day.” That’s part of the play’s power, she says. It isn’t letting this topic fall out of public discourse. “I think just by repeating and constantly reminding them, people become less scared.” She describes the events depicted in the play as “still taboo” and said it’s necessary for the audience to recognise that what happened to Tessa is criminal. “Something no one should have to abide.” She wants everyone to go away thinking about the play and what it depicts, and “rethink again, rethink again, rethink again.”

Dakić is referring to the fact that Serbian theatre recently had its own moment of reckoning. In 2021, drama teacher Miroslav Aleksić was accused of rape and sexual assault by several former students. He was eventually charged. Around the same time actor Danijela Štajnfeld’s released the documentary film Hold Me Right in which she talked to survivors of rape and discussed her own rape years earlier by a well-known Serbian actor. Though she did not reveal his name in the film, eventually she disclosed that the man accused in the film was Branislav Lečić, prominent Serbian actor and former Minister of Culture. The case was eventually dismissed in the courts due to insufficient evidence, but this did not stop Lečić embarking on a smear campaign against Štajnfeld. Lečić continues to perform in Serbian theatres, though at least one ensemble refuses to work with him and, when he was announced as a judge at the Susreti Theatre Festival in Brčko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 2022, it triggered a mass walk out, where one by one the productions withdrew from the competition programme in protest at his presence on the jury.

For the play’s pivotal speech, in which Tessa encourages the audience to look to the left and right, Dakić secretes herself under the autopsy table. Her intent with this scene, she says, is to allow the audience “to reflect, listen and - see. To find their own voice at that moment.”

“When you see that something is wrong, it can no longer be unseen.”

Lucie Ferenzova directed the play for Švandovo divadlo na Smíchově in a suburb of Prague. The actor Marie Štípková had been looking for a play to sink her teeth into and chose Prima Facie, and together with dramaturg David Košťák, designer Jana Hauskrechtová and costume designer Zuzana Scerankova, they discussed how to portray a world in which Tessa can go from feeling confidence to being the victim of a system “built up by men over centuries.”

They really leaned into the metaphor of the race, which Tessa uses in the beginning. Štípková starts off wearing a jockey costume, and as the play progresses the actress changes her jacket, so that it becomes increasingly ill-fitting. In addition to Štípková, there is a second performer on stage, Markéta Ptáčníková, and a drum kit, and the play is accompanied by live percussion.

Ferenzova’s production also uses a camera to shoot Tessa from above as she gives her testimony. When she looks into the camera, “she is looking into the system,” says Ferenoza. “The gaze becomes increasingly accusatory,” she says, “until it blurs.” By the end of the play, the drums have become a symbol of the machinery of the system. Ptáčníková’s presence is also crucial to the rape scene, where Tessa describes feeling a disembodied state. “The women intertwine on stage,” says Ferenzova, with Štípková observing her the other woman from afar.

Ferenzova attributes the play’s success to the cleverness of its construction and the way it depicts Tessa as two characters, “the lawyer, who knows how to work within -and has adapted to - a system built by men, and the victim of rape who finds the system inadequate for the needs of women.” Both perspectives exist with the same woman. Ultimately, says Ferenzova, Tessa defies the system to make her final speech. “We see that something is wrong, and when we know it, it can no longer be unseen. We may not know what, but somewhere, sometime, something has to change.” It is a message, she says, that goes beyond the legal system.

The response to her production has been positive. “I think the Czech audience feels the very urgent message that a long-silenced voice needs to be heard.” But, she adds, there have also been interesting responses (especially from the male members of the audience) that this is a form of propaganda and “that it is inciting a revolution that is not needed.” There have also been some people, mainly older women, who that the rape in the play is not really rape. However, these responses are in the minority, she stresses, concluding with a reminder that the Czech Republic has “again failed to ratify the Istanbul Convention, so we still have a lot to deal with in this regard... unfortunately. More texts like Prima Facie!”

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other exciting upcoming events over the next seven days

Mini NT – The Ivan Vazov National Theatre in Sofia, Bulgaria, is holding its first international showcase. Productions include The Hague, Moby Dick, Jernej Lorenci’s Orpheus. It opened on 27th February with Robert Wilson’s production of The Tempest and continues until the 2nd March (more on this in an upcoming edition).

INK -Renowned Greek director and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou brings his most recent piece of hyper-visual dance theatre to London this week as part of an ongoing international tour, with a run at Sadler’s Wells between 28th February and 2nd March.

JK Opole showcase – Poland’s JK Opole Theatre will be presenting a collection of its best productions of recent years for an international audience. The programme includes Four Good Reasons to Leave All of This Behind, helmed by artistic director Norbert Rakowski, and A Manual for Cleaning Women, directed by Olga Ciężkowska. It will also include an in-depth discussion of the Polish theatre system. The showcase takes place between 1st -3rd March.

Thank you for reading. If you find this newsletter enjoyable, interesting or otherwise valuable, please do share it or, if you are able, consider becoming a paid supporter. I publish monthly bonus subscriber editions - like this one about the Royal Court’s international department. I also have a Ko-fi account, if you want to support my writing that way. You can contact me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com