A cry in the dark: Oliver Frljić's Incubator

On the Croatian director's provocative response to the war in Gaza.

I’m writing this on a bus back from Ljubljana to Belgrade, having spent roughly 36 hours in the Slovenian capital. My corner of southeast Europe is deficient in trains (something I suspect still surprises people) and, as a result, I spend a lot of time on buses. This particular overland journey was undertaken to catch the latest work of a director who has long fascinated me: Oliver Frljić. He was one of the artists that cemented my interest in work being made outside of the UK, and the prospect of a new production was enough to make me undertake this cross-Balkan whistlestop trip.

This is the part where I point out that if you want to support my writing and have access to occasional paid subscriber bonus posts, you can do so for just £5 a month or £50 a year. Or, if that’s not doable - you work in theatre, I get it - just share this newsletter with someone you think might find it interesting. That helps too.

Oliver Frljić is a director who's never encountered a hornets’ nest that he didn’t want to stick his arm in all the way up to the elbow. Or, as he explains it in this excellent interview with Duška Radosavljević, he knew early on he had little interest in making work that swerved away from areas of risk. A significant figure on the European scene and, until recently the co-artistic director of the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, with Incubator, Frljić is making a return to the Mladinsko Theatre in Slovenia, site of early international success and a fruitful creative relationship with the dramaturg (and outgoing artistic director of the Mladinsko) Goran Injac, to make a piece in response to the ongoing war in Gaza, a topic I think it’s fair to say few theatres are willing to touch at the moment, at least not so explicitly.

There’s no beating around the bush here. No veil of metaphor. Ten minutes in and someone holds up a cardboard sign with the words Al-Shifa on it, the largest hospital in the Gaza strip. The cast wear military gear with the letters IDF on their backs. The show is fuelled by the news, reported early in the conflict, that premature babies were dying after their incubators stop working when the hospital’s power was cut, which is framed as the ultimate afront.

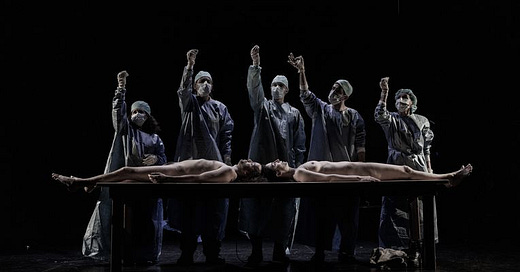

Like much of Frljić’s earlier work, Incubator is essentially a collection of skits and images with a unifying theme, devised with the cast. The actors begin by discussing their own passage into the world, when they were born and how much they weighed. The main props, and the focus of many scenes, are the incubators themselves, a machine designed to keep the most vulnerable – sick and premature babies – alive. (As he explains in this interview, there is personal resonance here as his own siblings were born prematurely but this clearly does not need to be the case for the image to be able to move you ). We see the red dots of rifle sights flutter over these incubators. We see them targeted with tinfoil bombs with the word ‘Gaza’ written on them.

Early on, one of the actors, Lina Akif, tells a series of bad taste jokes about Palestinians and then proceeds to laugh a too-loud, too-hard laugh that goes on for an almost painfully long time. The IDF soldiers take selfies of themselves standing over the bodies of journalists. Figures scuttle across the stage clutching plastic baby dolls only to be shot in the head.

Eventually the male performers drop their trousers and begin slow-motion humping the incubators to the strains of Smells Like Teen Spirit. As in his previous work, Frljić excels in finding imagery that interrogates moral boundaries and, in focusing so heavily on the slaughter of infants, he knows he’s playing on – or, arguably, simply deploying - antisemitic tropes, that imagery of infanticide is often used to evoke the blood libel, but he’s also acutely aware that a desire to avoid accusations of antisemitism can lead to self or institutional censorship, to no one saying anything. And how can that be tenable when babies are dying?

This queasy paradox is central to Incubator. Frljić’s imagery is never provocative for the sake of it. In interviews he comes across as thoughtful, rigorous and principled. He has made work in which an actor fellates a statue of Pope John Paul II, a woman in a hijab unfurls a flag from her vagina and a quintet of actors literally piss on a map of Yugoslavia. Are these things comparable with the imagery in Incubator? Does knowing that this is a tactic dilute the potential offensiveness? I watched the show having just read these recently published guidelines on confronting antisemitism and censorship in the arts, so they were very present in mind. I think it’s safe to say this show lands squarely in the grey area, albeit knowingly so.

Frljić has always been adept in anticipating and addressing the criticism that could be justifiably levelled at his work. As in several of his previous shows, Incubator contains a scene in which the performers debate each other’s biases. Here, the cast round on one of their number, Draga Potočnjak, who last year embarked on a hunger strike in solidarity with the plight of Palestinians, to ask her if she ever made any comparable statement about the victims of the October 7 massacre. Isn’t a failure to do so antisemitic? They accuse her of putting the company in a politically tricky position through her actions and not considering the potential impact on members of the ensemble who may be of Jewish heritage. At this point all eyes turn to Vito Weis, who then has to explain that while his name might sound Jewish, he himself is not. They keep questioning her. What is the point of her hunger strike, they ask? Isn’t it just the futile gesture of a privileged western white woman? If Potočnjak wanted to make a difference, why not do something more drastic? Why not take a real risk? They ask why she feels deeper reserves of rage and compassion for Gaza than, say, Yemen, Sudan or the casualties of any other global conflicts. They start singling out other members of the company and asking them to define where they stand and why. It becomes personal and barbed, with the actual conflict, the lives being lost, paling into the distance.

Archly deconstructive scenes like these are a characteristic of Frljić’s work. In many ways Incubator echoes his 2010 show Damned by the Traitor of His Homeland!, also made with the Mladinsko ensemble, which probed several Slovenian sore spots and had the actors challenging each other’s right to define themselves as Slovenian. It’s a tactic he uses a lot, acknowledging and weaving the performers’ own positions into the performance. More than one of his shows contains a scene in which the actors lambast him for leaving them having to perform this contentious material while he fucks off to the next project.

This was probably most apposite in The Curse, his 2017 production for Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, which tackled sexual abuse in the Catholic Church and included the papal fellatio scene. It enraged the Polish authorities and led to threats being made against the actors. The Polish Culture Minister at the time rescinded funding for the Malta Festival (which, confusingly, is in Poland) which Frljić and Injac were guest curating at the time. The festival went ahead with a newly inserted scene in Frljić’s own production of Turbofolk which told the Polish Culture Minster to fuck off.

Incubator feels like a different form of ‘fuck you,’ but one born of out of frustration, and perhaps a sense of artistic impotence, a compelling need to speak out, to shout out, to do something, as Israel maintains a stranglehold on aid getting into Gaza.

A later scene, detailing the history of hostage exchange, explores the implications of many hundreds of Palestinian prisoners frequently being released in exchange for a single Israeli, and how it illustrates that a Palestinian life is worth only a certain percentage of an Israeli life. The maths for this equation is written out on Blaz Shef’s naked back, before an amount of meat equivalent to two Palestinians is prepped and seasoned before being cooked on a grill. This is wheeled off stage, but the smell of grilling beef seeps through the auditorium anyway. Eventually, the meat is fashioned into kebabs and offered to the audience. I’m fully aware that allusions to cannibalism are also loaded and coded, and while I think this show is intentionally poking these tropes, testing the limits as Frljić’s work so often does, I think it veers close to the line at times.

(Incidentally, it’s only later when someone holds up a picture of the Nevermind album cover that I twig why Nirvana has played such a big part in the soundtrack. Frljić is clearly not content to let the audience make the connection on their own – there’s little space for subtlety here).

Then Lina Akif then squats at the front of the stage, spreads her legs and smears her inner thighs with red as if going through a protracted labour without assistance or pain relief, howling with the same unrelenting force with which she laughed earlier in the show, screaming and screaming and screaming. Eventually the glistening crimson baby doll which emerges from between her legs enacts a little puppet show, playing Edward Said opposite a baby Hannah Arendt.

While Frljić’s work in Berlin has included the somewhat prescient Alternative for Deutschland? - in which the Gorki’s reputation as a ‘post-migrant’ theatre was deconstructed by the largely migrant members of its own ensemble, while also shining a light on the rise of the far right AfD in Germany - recent years have seen him pivot towards material based on literary works. His epic production of The Brothers Karamazov at the Zagreb Youth Theatre (ZKM), was widely acclaimed – he joked that he’d been away for so long, the Croatian audiences had forgotten why they hated him. Recent productions at the Gorki have included versions of Alice in Wonderland and Frankenstein. The most recent production of his I saw there was a version of Kafka’s The Trial, which felt a bit muted and by-numbers until the abrupt inclusion of an image of Aaron Bushnell, the young US serviceman who set himself on fire in protest against US complicity with what was taking place in Gaza, in the final moments. It felt like the work of a director with one hand tied behind his back.

One could argue that Incubator is a backward step, a return to a mode of making work that grew familiar enough for one conservative Croatian commentator to dismiss it as a mechanical principle, a formula, a kind of Frljić-engine which combines symbols of national or religious sensitivity with the crass or profane to appal/amuse a polite theatregoing crowd. Or you could read it as a kickback against artistic restrictions as they manifest in Germany in respect of making any work, or even any statement, about Israel’s actions in Gaza. As they state in the show, there’s absolutely no way you could do this in a country like Germany, or even Sweden. (It’s telling that in the UK the show that says the most about these issues is a play that is ostensibly about a cantankerous children’s author). Is there something adolescent about Frljić’s approach? Undoubtedly. But there’s also a sense of obligation, a sense that theatre has a duty to speak out and speak loudly, to fill the silence, to react to horror of such magnitude. If it can’t do that, what is theatre for? Am I convinced that this is the best way to do that? Not wholly, even though I was completely here for it when he was intent on dredging up things unspoken and collectively suppressed in a post-Yugoslav context.

The production ends with a section looking at how different countries have circumnavigated or simply dismissed the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant for Benjamin Netanyahu. Strangely absent from this discussion is the fact that Slovenia recognises the state of Palestine and has said it will respect the arrest warrants. Yes, this is a show Frljić- could never have made at the Gorki, but it’s also a show he could make– and indeed has made – in Ljubljana. It has, at the time of writing, not created any major scandal or upset. The lack of acknowledgement of this context undercuts it to an extent. Too often I felt I was watching the show Frljić wanted, and maybe needed, to make in Berlin, rather than one that fully engaged with the audience for which it was being made.

This week in European theatre

A round-up of festivals, premieres and other upcoming events over the next seven days.

Year Without Summer - Austrian choreographer Florentina Holzinger is currently one of the most in-demand artists in Europe. Her recent shows Sancta and Ophelia’s Got Talent have both been enormous hits. Her new work, Year Without Summer, takes its name from the summer of 1816, where climate abnormalities led to the coldest summer on record in Europe, during which Mary Shelley, cooped up in a chalet on Lake Geneva, wrote Frankenstein. It premieres at the Volksbühne in Berlin on 21 May.

After the Act - Breach Theatre’s musical is inspired by Section 28, the infamous law which banned the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools in the UK. Weaving together interviews with activists, teachers and former pupils about the impact the legislation had on the people’s lives, it starts a run at London’s Royal Court on 23 May.

Article 55 - Director Tjaša Črnigoj’s follow-up to the five-part Sex Education II project, which explored women’s desire and reproductive rights, is a documentary piece about Article 55 of the Slovenian constitution. which states "Everyone shall be free to decide whether to bear children.” This right was written into the Yugoslav constitution in 1974, but was contested as Slovenia moved towards independence. Črnigoj’s show is based on interviews with the activists who fought to retain these rights. It premieres at the Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana on 24 May.

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, tips, or thoughts about this newsletter, you can reach me on natasha.tripney@gmail.com